Argument Analysis

5 Missing Premises

Section 1: Introduction

As we have seen, when people do not use indicator words it can be difficult to determine their intended argument. There is a further fact of life that complicates argument analysis: not only do people sometimes leave out indicator words, but often they leave out whole premises. While this might be surprising, we will see that in many cases there are good practical and rhetorical reasons for leaving assumptions implicit. Moreover, being able to spot argumentative gaps and identify missing premises can be crucial for understanding arguments, and seeing their problems. After all, people do not tend to formulate or express arguments in ways that make the argument look obviously bad. Rather, when arguments are poor, often the fault lies in what has been merely assumed or left unsaid.

Section 2: Argumentative Gaps and Missing Premises

Let us begin with a relatively simple example. Suppose a student says:

Ex. 1:

This course is a waste of my time since it doesn’t contribute to my major.

Given what we have learned so far, we should standardize and diagram the student’s argument as follows:

- This course doesn’t contribute to my major.

- So, this course is a waste of my time.

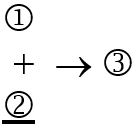

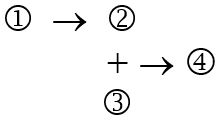

![]()

Moving forward, we will call this form of analysis, Surface-Level Analysis. This is an example of surface-level analysis because it represents only what the author has explicitly stated—nothing more. Given this, we can distinguish surface-level standardizations and surface-level diagrams accordingly. Overall, surface-level analyses can be very useful, and we will continue to use them throughout this book. However, sometimes we need to look behind the explicit statement of an argument, and this calls for a different form of analysis.

With this in mind, the important thing to notice about the argument in Ex. 1 is that it has a gap. The author makes one claim about the course in the premise, namely that it doesn’t contribute to the speaker’s major, but then leaps to a different claim about the course in the conclusion, namely that it is a waste of the speaker’s time. What does the premise have to do with the conclusion? After all, these are distinct characteristics of the course. Why does the fact that the course doesn’t contribute to her major mean that it is a waste of her time? This is just one example of a gap, but we can define argumentative gaps more broadly along similar lines. We will say that an argument has a gap when (and only when) it does not explicitly connect the premises to the conclusion.

Now although the speaker has not explicitly spelled out what the premise has to do with the conclusion, she clearly thinks they are related. So what is the connection here? There are a number of ways the speaker might be thinking about this connection, but for now we will formulate it as follows:

- This course doesn’t contribute to my major.

- Courses that don’t contribute to my major are a waste of my time. (MP)

- So, this course is a waste of my time.

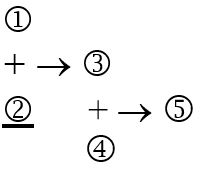

We’ve bridged the gap in this argument by going beyond the stated argument and adding a premise that explicitly connects the claim in the premise that the course doesn’t contribute to her major to the claim in the conclusion that the course is a waste of time. We will call any analysis that adds a connective premise, a Deep Analysis, and we can distinguish deep-level standardizations and deep-level diagrams, accordingly. It is important when using deep analysis to distinguish an author’s explicitly stated premises from the premises we attribute to the author. Consequently, we will adopt the following convention: after an added premise in a standardization we will write MP (for missing premise) in parentheses as above.

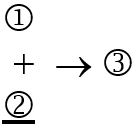

How do we include missing premises on a diagram? We add missing premises to an analysis to show how the stated premise connects to the conclusion. As a result, in our diagrams missing premises are always added (‘+’) to the stated premise. Thus, in this case we will add the missing premise (2) to the stated premise (1). In addition, as in standardizations, we will want to mark that we have added a missing premise. We will do so by underlining the number of the missing premise. Thus, the deep diagram of Ex. 1 will look like this:

Let us consider another example:

Ex. 2:

Jenna is not eligible to run for the U.S. Senate given that she is only 25 years old.

A surface-level standardization and diagram of this argument looks like this:

- Jenna is only 25 years old.

- So, Jenna is not eligible to run for the U.S. Senate.

![]()

As stated, this argument contains a gap; the author is leaping from a claim about Jenna’s age to a claim about her ineligibility to run for the U.S. Senate. Again, it is fair to ask: what does one have to do with the other? Clearly, the author sees the premise as evidence for the conclusion, but how so? The author seems to be assuming that there is some bridge between being only 25 years old and being ineligible to run for Senate. This unstated assumption taken together with the stated premise would connect to the conclusion. Again, there are a number of ways that the author might be thinking about this connection, but for now we will say that the missing premise is ‘Anyone who is only 25 years old is not eligible to run for the U.S. Senate,’ and we will give a deep analysis of the argument as follows:

- Jenna is only 25 years old.

- Anyone who is only 25 years old is not eligible to run for the U.S. Senate. (MP)

- So, Jenna is not eligible to run for the U.S. Senate.

Again, note that we have marked the addition of the missing premise in the standardization by writing ‘MP’ after the missing premise, and have marked it in the diagram by underlining the number.

It is important to note that adding missing premises can sometimes feel redundant or repetitive. This feeling, in part, grows out of the fact that a missing premise will normally use the same terms found in the premise and conclusion. Nevertheless, a missing premise says something different (see the examples above). That is, a missing premise makes a claim that is distinct from either the premise or conclusion, and so is not redundant. Indeed, it is precisely because it is making a claim that differs from both the premise and the conclusion that it can serve to bridge or connect the two.

Section 3: The Golden Rule of Argument Interpretation

Let us briefly review what we did above. In both Ex. 1 and Ex. 2 we noticed an argumentative gap: namely that the premises didn’t explicitly connect to the conclusion. In light of this, we might have inferred that these are simply poor arguments whose premises are irrelevant to the conclusion. But we didn’t. In each case, we gave the author the benefit of the doubt, and assumed they must have left something out. That is, we assumed that the author had drawn on some unstated connection between the premise and the conclusion. Why give the benefit of the doubt in these cases? That is, why not just conclude that these are poor arguments, and move on?

Well, if you think about it, you’ll realize that we almost never make all our premises explicit. Often it would take too long to communicate every detail of our thinking, and in many cases, there is no need to make our assumptions explicit since our audience shares them. To return to our original question, the reason to give the benefit of the doubt is that you would want to be given the benefit of the doubt if your roles were reversed. After all, most of the time you don’t make every premise of your thinking explicit, and you wouldn’t want your arguments rejected on these grounds.

This brings us back to the Golden Rule of Cooperative Dialogue. As we’ve seen, the first rule of cooperative dialogue is to treat your interlocutor as you would like to be treated, and this is a specific application of the general rule. The rule tells us that we should try to interpret other people’s arguments in a fair and plausible way based on the assumption that they are, like you, a reasonable person. This application of the Golden Rule of Cooperative Dialogue is so important that we’ll give it its own name, and call it the Golden Rule of Argument Interpretation.

The Golden Rule of Argument Interpretation: When engaging cooperatively, interpret other’s arguments in a fair and plausible way.

Although we are making this principle explicit here, this is not the first time we’ve drawn on it. Recall the example from the last chapter about whether Jack Martinez should be in the hall of fame. In that case we were faced with an ambiguous argument, and we ended up attributing the most plausible interpretation of the argument to the author, and we did so in an effort to understand the argument in a way that was fair to the author. Indeed, understanding is the ultimate goal here. Remember, cooperative dialogue is a way of engaging with others to increase understanding and improve decision making, and by following the Golden Rule of Argument Interpretation we put ourselves in a position to better understand another’s argument.

A final point to emphasize here is that there is a big difference between understanding an argument and agreeing with it. To give an author or speaker the benefit of the doubt, and to interpret their argument in a fair and plausible way is to try to understand what another reasonable person thinks. However, reasonable people make mistakes, and reasonable people can disagree. To understand somebody else’s position is simply to get their view straight, and once we’ve done so, we are free to evaluate it and form our own views about its truth or accuracy.

Section 4: Uncovering an Author’s Unstated Reasons

Every time we draw an inference we leave a great deal implicit. The author of the argument in Ex. 2, for instance, is making a wide variety of assumptions including (among others) that:

- There is a person named Jenna.

- There is a place called U.S.

- The U.S. has a Senate.

- The Senate is something people run for.

- Running for the Senate is something that a person can be ineligible for.

Thus, in even simple cases it isn’t practical (or interesting!) to try to identify all a person’s assumptions. So, what assumptions should we include in a deep analysis of an argument?

When it comes to argument analysis, we are interested primarily in how the author’s stated premises connect to the conclusion, and these are the only assumptions relevant to deep analysis. Put differently, in analysis we are only interested in the piece of information that would bridge the gap between the stated premise(s) and the conclusion. Given this, we will adopt the following rule with regard to an author’s assumptions:

Rule for Missing Premises: In the analysis of an argument, include as missing premises only those assumptions that are required to connect the stated premise (or premises) with the conclusion.

The Rule for Missing Premises tells us that we should only include missing premises that are required to bridge an argumentative gap. Assumed information that is not required to connect the stated premises to the conclusion should be left out of a deep analysis of the argument. Given this, the next question we need to take up concerns how we identify the proposition that bridges the argumentative gap?

As we have seen, the missing premise needs to relate the stated premise to the conclusion, and in order to fill this role the missing premise(s) will need to say something about the subject matter of the premise and something about the subject matter of the conclusion. Let’s go back and think about Ex. 1. Recall that we began with the Surface-Level standardization:

- This course doesn’t contribute to my major.

- So, this course is a waste of my time.

We proposed the following missing premise:

(MP): Courses that don’t contribute to my major are a waste of my time.

In the missing premise the subject matter of the premise is in red, and the subject matter of the conclusion is in blue. The proposed missing premise is one way of bringing these two subjects together to show how the truth of 1) supposedly bears on 2). Specifically, the fact that the course doesn’t contribute to this student’s major purportedly shows that the course is a waste of time because the student is assuming that courses that don’t contribute to her major are a waste of time. In general, when trying to identify and formulate missing premises, it is useful to take the comparison of a missing premise to a bridge seriously. Just as a bridge over a river needs to physically connect both sides, so too, a missing premise needs to connect, in terms of its content, the stated premise(s) to the conclusion.

Let’s put this to work in another example.

Ex. 3

Chris: Is Avengers: Endgame a good movie?

Sadie: Obviously! I mean, it is the highest grossing movie in history.

A surface-level analysis of Sadie’s argument looks like this:

- Avengers: Endgame is the highest grossing movie in history.

- So, Avengers: Endgame is a good movie.

Again, we have an argumentative gap. The stated premise does not explicitly connect to the conclusion. Given the Golden Rule for Argument Interpretation we will take for granted that the author is drawing on some connection between the two. In order to bridge the gap, the missing premise will have to start from the content of the premise, and extend to the content of the conclusion. That is, it will need to relate being the highest grossing movie of all time to being a good movie. Moreover, in doing so, we will need to stick close to the author’s original language, since we don’t want to inadvertently transform the argument into something different. How do we do this? At this point, adding missing premises can get difficult. As it turns out, there are many ways of connecting these two characteristics into a single premise while sticking close to the author’s language. We might, for example, connect them in a direct and literal way:

(MP1): The highest grossing movie of all time is a good movie

While this bridges the gap, it seems overly specific. As an alternative, perhaps Sadie is making an assumption about all high-grossing movies, not just the highest grossing:

(MP2): All movies that gross a lot of money are good movies.

Again this bridges the gap, but this proposed missing premise seems too broad. Perhaps Sadie is assuming something a bit more tentative, but which nevertheless connects the relevant characteristics:

(MP3): Movies that gross a lot of money tend to be good movies.

There are many other ways we might bridge the argumentative gap here. So, how do we know which one Sophie is assuming? In short, without talking to Sophie, we don’t know. The best we can do is to choose the premise that strikes us as the most plausible, and MP3 is the most plausible among these options. This means that different people may attribute slightly different missing premises to the same speaker or author. That said, there will be a limited range of acceptable missing premises—namely those missing premises that stick closely to the author’s original language, connect the content of the stated premise to the conclusion in a way that shows why the truth of the stated premise supports the truth of the conclusion, and does so in a plausible way.

Section 5: Deep Analysis in More Complicated Cases

So far we’ve looked at simple arguments with only one premise. As we’ve seen however, there are all kinds of arguments. In this section, we will take a look at how deep analysis works in more complicated cases. Let us start with a simple argument with multiple premises. Consider the following:

Ex. 4:

There is no point to student government. They only have the power to make requests to the administration, these requests are rarely fulfilled, and the election process is mostly a popularity contest.

The first sentence of this example is the conclusion. The author then gives three reasons on behalf of the conclusion (without using indicator words). The surface-level standardization and diagram for this argument is:

- Student government only has the power to make requests to the administration.

- Requests from the student government to the administration are rarely fulfilled.

- The election process for student government is mostly a popularity contest.

- So, there is no point to student government.

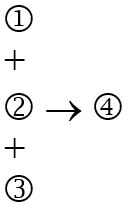

There is a gap in this argument. The first two premises seem to go together because they note that student government has limited power to effect change, and the third is a proposition about the election process. In contrast, the conclusion says there is no point to student government. What do the premises have to do with the conclusion? Given the Golden Rule for Argument Interpretation, we’ll take for granted that the author is assuming that the premises support the conclusion, and so the task is to figure out how the content of the premises could support the content of the conclusion. Here is one way:

(MP): Student government doesn’t have a point if it can’t effect change and the election is about popularity.

The color coding shows how the content of the premises and the conclusion is contained within the missing premise. Green captures the idea that student government doesn’t have much power to act or create change; red captures the idea that the election process is about popularity, and blue captures the idea that there is no point to student government. There are other ways of formulating the missing premise, but, again, any acceptable missing premise will have to connect the content of the premises to the content of the conclusion. Given this missing premise, the deep standardization and diagram look like this:

- Student government only has the power to make requests to the administration.

- Requests from the student government to the administration are rarely fulfilled.

- The election process for student government is mostly a popularity contest.

- Student government doesn’t have a point if it can’t effect change and the election is about popularity. (MP)

- So, there is no point to student government.

Let us turn to a different example, namely the case of a complex argument. Consider the following:

Ex. 5:

The chemical BPA has been shown to disrupt endocrine function in mice, and this suggests that humans should limit their exposure to this chemical. Since BPA is found commonly in plastics, we should try to limit our exposure to such wrappings.

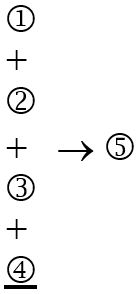

A surface-level standardization and diagram of this argument looks like this:

- The chemical BPA has been shown to disrupt endocrine function in mice.

- So, humans should limit their exposure to BPA. (from 1)

- BPA is found commonly in plastic food wrapping.

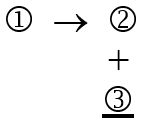

- So, we should try to limit our exposure to such wrappings. (from 2 and 3)

This argument illustrates two complexities. First, as a complex argument there are two inferences here: from 1 to 2 and from 2 and 3 to 4. This means that there are two possible argumentative gaps (one for each inference). A look at the first inference reveals a gap: the premise tells us about endocrine disruption in mice, whereas the conclusion tells us humans should limit their exposure to BPA. What, exactly, is the connection between these two facts? Connecting the content of 1 (red) and 2 (blue) will lead us to something like this:

(MP): Humans should limit their exposure to chemicals that disrupt endocrine function in mice.

What about the other inference? This brings us to the second notable element of this example. There is no gap in the argument from 2 and 3 to 4. The content of 2 and 3 directly relates to the content of 4, and it is clear how the truth of 2 and 3 establish the truth of 4. The takeaway here is that while most arguments contain gaps, not all do. Ultimately, our deep standardization and diagram of Ex. 5 will look like this:

- The chemical BPA has been shown to disrupt endocrine function in mice.

- Humans should limit their exposure to chemicals that disrupt endocrine function in mice. (MP)

- So, humans should limit their exposure to BPA. (from 1 and 2)

- BPA is found commonly in plastic food wrapping.

- So, we should try to limit our exposure to such wrappings. (from 3 and 4)

We do not always need to take the time to identify missing premises. It can be quite useful, however, and is not too difficult to learn with some practice. Before we turn to the exercises, however, we’ll take up one final issue: our awareness of our own reasons.

Section 6: Awareness of One’s Reasons

Go back to Ex. 3. We might look at the missing premise and feel like something fishy is going on. After all, did Sadie really think to herself: ‘Movies that gross a lot of money tend to be good movies’? The answer is probably ‘no’. It seems much more plausible that she inferred the conclusion from the premise without explicitly identifying this proposition in her thinking. Yet, if she didn’t think it explicitly, can we really say that it was part of her intended argument? That is, can a person intend an argument if they don’t explicitly identify all of the argument’s premises in their thinking? Sure.

We each have a vast and complex system of belief, though at any given time we are explicitly aware of only a few beliefs. For example, you believe that you are a particular age, that your birthday is on a particular date, and that your first pet was named so-and-so. However, most of the time you do not pay attention to these beliefs. In fact, you probably weren’t thinking about any of these beliefs until just now. In addition, these dormant or implicit beliefs can inform our thinking and acting. Here is an example: suppose you wake up and walk to the bathroom to brush your teeth. You open the cabinet to get your toothbrush. In doing so, you probably did not think to yourself, ‘the toothbrush is in the cabinet’ and ‘I need to open the cabinet door to get it’. Although you were not explicitly thinking these beliefs as you acted, it seems clear that you nonetheless have these beliefs and that they informed your action.

Furthermore, as we saw back in Chapter 1 there are unconscious and semi-conscious belief-forming processes constantly at work within us. These processes are a way of quickly updating our system of belief in light of new information from our environment. As we navigate the world we engage with it at different levels, and can soak up patterns, norms, and values from our surroundings. A notable consequence is that it is possible for us to have beliefs that we do not even know about. This means that our viewpoints and decisions may be a consequence of beliefs we are not aware we have—beliefs we maybe wouldn’t endorse if we did think about them explicitly.

Uncovering the hidden assumptions of an argument is one of the most valuable consequences of the process of argument analysis. The reason is that when people’s reasoning is poor, it is often poor because these hidden, presupposed, or suppressed assumptions are false. It is easy for people to hold false or implausible beliefs when these beliefs remain below the level of conscious awareness. Consider the argument in Ex. 1. A deep analysis of this argument shows that it assumes that all or most courses that don’t contribute to a person’s major are a waste of time. But is that really true? When we explicitly identify this assumption, this argument seems a lot less persuasive than it might have initially. Furthermore, reflecting on this assumption might ultimately lead the student to rethink her attitude towards course work.

Exercises

Exercise Set 5A:

Directions: For each of the following determine whether the passage contains an argument. If it does not, write “no argument”. If it does, (i) give a deep standardization of the argument, making sure missing premises are added in accordance with the Rule for Missing Premises, and (ii) diagram it on the basis of this standardization.

#1:

Of course you can get direct international flights from Windhoek to New York—Windhoek is Namibia’s capitol city, after all.

#2:

I deserve at least a B on the assignment on the grounds that I worked really hard.

#3:

I don’t have any symptoms, so I can’t spread the virus.

#4:

Kyle is related to the Johanssons? I bet he is going to be trouble when he is older.

#5:

The PTA’s suggestion that in order to protect children from sunburn, a rule should be instituted requiring all children at our school to wear a sun hat when they are outside after 11 a.m. is unacceptable. For clearly such a rule would be an infringement upon the freedom of the individual.

#6:

Judge Zito’s policy of taking away the driving licenses of people charged with DUI who are awaiting trial is unconstitutional because the policy does not treat people as if they are innocent until proven guilty.

#7:

A: Illegal immigrants are stealing our jobs!

B: No they aren’t. How can they steal jobs that nobody wants?

#8:

If I had to say, I’d say that Kelsey is probably a very good swimmer. Why? Well, she is on the swim team—or at least I think she is on the swim team. I mean I’ve seen her walking around wearing swim team gear.

#9:

The proposed ban on high-capacity magazines doesn’t make any sense. Think about it: a ban on high-capacity magazines wouldn’t necessarily prevent any of these mass killings, since with practice a person can learn to swap out a depleted 7 round magazine in a couple of seconds or less.

#10:

There is no need for me to wear a mask, since I’ll be fine if I get the virus. After all, I’m young and don’t have any health problems.

#11:

I am in favor of returning America to the gold standard. Not only would it limit inflation, but it would force greater fiscal constraints on governments because they couldn’t simply print money to pay their debts or bail out bankers. Moreover, it would bring the kind of stability to the monetary system that it had a hundred years ago.

#12:

We cannot hold the Scandinavian countries’ health care systems as a model to copy in the U.S., for their populations are almost completely homogeneous. The respective populations of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland are almost wholly white, Protestant, economically affluent, and highly educated. Furthermore, we cannot even hope to model these health care systems, given that in these countries the ratio of resource wealth to population is much higher than our own. Thus, we will have to be creative and come up with our own solutions to the current health care crisis.

Exercise Set 5B:

#1:

What is wrong with the following diagram? Explain.

#2:

Make up an argument with a gap. Then identify the missing premise, and give a deep analysis of it.

#3:

In the discussion of Ex. 3, the text says that MP3 is the most plausible of the potential missing premises. Why is that do you think? Explain.

#4:

Consider the following argument:

I think she is an English major, since she reads a lot.

What is wrong with proposing the following missing premise?

(MP): People who are English majors usually read a lot.