Argument Analysis

4 Complications to Argument Analysis

Section 1: Introduction

As we have seen, we are not in a position to fairly evaluate an argument until we have accurately determined its structure. That is, argument analysis is a prerequisite for argument evaluation, and in the last chapter we introduced a number of terms and techniques for analyzing and representing arguments. In this chapter, we take a look at a number of complications to the process of argument analysis. The most important of these complications has to do with the absence of indicator words. Authors and speakers often express arguments without using indicator words, and this can make the process of analyzing their arguments particularly difficult. The chapter closes with a general method for looking behind an author’s words to see their intended argument. Overall, the chapter emphasizes the importance of paying close attention to the language and goals of argument.

Section 2: A Tricky Indicator Word: ‘because’

Consider the following example:

Ex. 1:

Dara and Chatri are sitting in Dara’s car. They have spent the last 15 minutes trying (and failing) to start the car, when Chatri says: “I bet the car won’t start because it is out of gas.”

It is tempting to read ‘because’ as indicating a premise, and to interpret Chatri’s comment as expressing the following argument:

- The car is out of gas.

- So, I bet the car won’t start.

That seems straightforward, but something isn’t quite right here. Dara and Chatri are sitting in the car together; they have been trying and failing to start the car for 15 minutes. Wouldn’t it be a little weird for Chatri to offer evidence that the car won’t start? Chatri and Dara already know that the car won’t start! What they are looking for is an explanation for why it won’t start.

The problem here is that the word ‘because’ can be used to express two closely related, but distinct, relationships. On the one hand, it can be used to indicate that a premise is being offered as evidence in support of a conclusion. Let us call this the Evidential Use of the term ‘because’. The term is also commonly used to indicate that an explanation is being offered for some state of affairs. This is how the term is being used in the example above. Let us call this the Explanatory Use of the term. Let’s look at another example to help clarify this difference.

Suppose that there was an extended power outage at a local school yesterday. The next day you are discussing the outage with some other people in your community, and somebody says:

Ex. 2:

The school lost power because a construction crew dug through an electrical cable.

Is this an evidential or an explanatory use of the term ‘because’? If it is an evidential use of ‘because’, the person is giving evidence that the school lost power. However, this wouldn’t really make sense—everybody already knows the power went out at the school. The interesting question in this context is what caused the power outage in the first place, and that is what the speaker is offering—an explanation. We can compare this to an evidential use in the same conversation.

Ex. 3:

The school probably won’t experience an extended power outage like that again because they are installing a backup generator.

In this example, the person speaking is talking about the possibility of a future power outage, and this is not the sort of thing that it makes sense to explain. After all, nothing has happened yet! Instead the speaker is giving us a reason for thinking that this prediction is accurate.

In general, when you see a ‘because’ you will want to keep the following questions in mind: What is the sentence about? Is it talking about something that is widely unknown or debatable? If so, it would make sense to give evidence for it, and the word ‘because’ is probably introducing an argument. Alternatively, is it talking about some commonly known or obvious fact? If so, the situation doesn’t call for evidence, and the word ‘because’ is probably introducing an explanation.

It is important to raise one further issue when it comes to arguments and explanations, namely that we can argue on behalf of explanations. Put otherwise, although arguments and explanations are different, we can bring the two together by giving reasons for thinking that some specific explanation is right. To illustrate, let us return to Ex. 2. There are many possible explanations for why the school lost power, and it would be fair to ask the speaker “how do you know it was because a construction crew dug through an electrical cable?” In reply, to this question about evidence suppose the speaker says: “Because it was in the newspaper this morning.”

In this case, the speaker is using the term ‘because’ in both evidential and explanatory senses. We can standardize the speaker’s as follows:

Ex. 4:

- The newspaper said the school lost power because a construction crew dug through an electrical cable.

- So, the school lost power because a construction crew dug through an electrical cable.

Here the speaker is offering evidence on behalf of the proposed explanation. That is, the speaker is arguing that a specific explanation is correct. Arguments for explanations are extremely common, and we will take a closer look at them in Unit #5. For now, however, we will turn to a different complication to argument analysis.

Section 3: Seeing Behind an Author’s Words

Indicator words are a valuable aid in argument analysis, but in most cases indicator words alone will not reveal an argument’s structure. The chief reason is that authors and speakers do not always mark every inference they make using indicator words. In fact, sometimes an author or speaker will present an argument without using any indicator words. Why wouldn’t someone use indicator words? Sometimes, people do so because they take it as obvious that they are making an inference, other times people do so for rhetorical reasons.

Whatever the reasons, most arguments do not wear their structure on their sleeves, so to speak. This makes the task of argument analysis significantly more complicated. Since the author or speaker has not made the structure of their argument explicit, we are forced to look behind their words to see their intended argument—and this can be tough. How are we supposed to know what an author’s intended argument is, if they do not explicitly tell us? Unfortunately, there is no easy answer to this question; however, there are some strategies that are fairly reliable means to finding an author’s intent.

The first, and most important, step is to find the main conclusion. This is the focal point of the argument to which all the relevant parts of the argument are attached. We find the main conclusion by asking: “what is the point here?” and “What does the author want me to take from this piece?” Once you’ve found the main conclusion, you are in a position to work backwards to uncover the argument’s structure. Thus, the next task is to find the main reasons the author uses to directly support the main conclusion. We look for these reasons by asking: “what reasons does the author give for thinking the main conclusion is true?” Once we’ve uncovered these reasons, we are not done. After all, the argument may have multiple layers; it may be a complex argument in which the author has also argued for the main reasons. This means we need to look to see if the author has given any second-level reasons as evidence for the main reasons. We do this by asking for each main reason: “what reasons does the author give for thinking that the main reason is true?”. Once we have uncovered any second-level reasons, we can proceed to look for third-level, fourth-level, and fifth-level reasons (and so forth). You will want to continue this process until you’ve captured the whole extended argument. To see how this works, let’s take a look at an example.

Ex. 5:

Mega-Mart executives often say that Mega-Mart stores ultimately benefit the community. This just isn’t right. When are people going to wake-up? The presence of a Mega-Mart store in a community actually drives down wages, and the money spent at Mega-Mart does not stay in the community. Further, its presence drives local businesses to close, since small family-run operations cannot compete with the buying power of a gigantic corporation like Mega-Mart.

The first step is to identify the main conclusion. To that end, we’ll ask: what is the point of this piece? In this passage, the author is vehemently disagreeing with the claim that Mega-Mart stores ultimately benefit the community, and he backs this up. This tells us that the point—and main conclusion—of this passage is that “Mega-Mart stores do not ultimately benefit the community.” Notice that the author does not say this explicitly, writing instead that “This just isn’t right” where “this” refers back to the claim that Mega-Mart stores ultimately benefit the community. Once we know the main conclusion, we can work backwards by asking, “what reasons does the author give for thinking the main conclusion is true?” In this case, it is not too difficult to identify these reasons, since the author immediately turns to three ways Mega-Mart stores harm communities: Mega-Marts drive down wages, the money spent at Mega-marts does not stay in the community, and that the presence of a Mega-Mart store drives local businesses to close. Consequently, these are the author’s main reasons.

Our next question is whether the author has second-level reasons. In other words, we need to figure out whether the author offers any evidence on behalf of the main reasons above. Helpfully, the author has given us an indicator word, claiming that “its presence drives local businesses to close, since small family-run operations cannot compete with the buying power of a gigantic corporation like Mega-Mart.” So, this is a second-level reason. That covers everything the author says in this passage. We’ve captured all the author’s reasons, and so we can go ahead and put together our final standardization and diagram as follows:

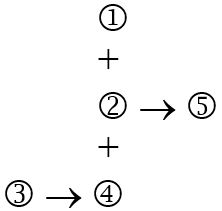

Standardization and Diagram of Ex. 5:

- The presence of a Mega-Mart in a community actually drives down wages.

- The money spent at Mega-Marts does not stay in the community.

- Small family-run operations cannot compete with the buying power of a gigantic corporation like Mega-Mart.

- So, the presence of a Mega-Mart drives local businesses to close. (from 3)

- So, Mega-marts do not ultimately benefit the community. (from 1, 2, and 4)

Section 4: Analyzing Ambiguous Texts

It wasn’t too difficult to identify the author’s main reasons in Ex. 5, but it is not always so easy. Sometimes it will not be clear at all how an author is arguing, and this raises an important question: How do we find the author’s reasons if they aren’t obvious? Here is an example to help us think through the problem.

Ex. 6:

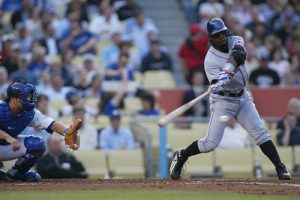

There is no room in the hall of fame for Jack Martinez. His batting statistics weren’t earned since he took performance enhancing drugs. Not only that, but he was a divisive figure who undercut the success of his teams.

The main point of this passage is expressed in the first sentence. The next step is to look for the author’s main reasons. The sentence that immediately follows begins by telling us that his batting statistics weren’t earned. The author hasn’t used an indicator word, but this is one of the author’s main reasons since it supports the main conclusion. The author continues: “since he took performance enhancing drugs.” This is evidence for the main reason, so let’s put it aside until we get to a consideration of second-level reasons. The last thing the author says is that Martinez was a divisive figure who undercut the success of his teams. The author thinks it is relevant to the argument (saying “not only that”), but where does it fit into the overall argument? It is hard to tell. What should we do? Well, there are a number of ways it might fit into our analysis. Let’s look at each one, and see if anything sticks out.

Option #1: The author thinks that the fact that Martinez was a divisive figure who undercut the success of his teams is evidence that he took performance enhancing drugs.

It seems unlikely that this is the inference the author is making. What does being a divisive figure have to do with taking drugs?

Option #2: The author thinks that the fact that Martinez was a divisive figure who undercut the success of his teams is evidence that his batting statistics weren’t earned.

Again, it seems unlikely that this is what the author intends. What does being divisive have to do with whether a person’s batting statistics were earned or not?

Option #3: The author thinks that the fact that Martinez was a divisive figure who undercut the success of his teams is evidence that he doesn’t belong in the hall of fame.

Of the three options, #3 is the most plausible. It is not difficult to see how a person might think these characteristics of Martinez are relevant to whether he belongs in the hall of fame. As a result, it seems most likely that the author is using the fact that Martinez was a divisive figure as one of the main reasons for the main conclusion.

Notice the procedure here. In the face of an ambiguous argument, we identified three different ways of eliminating the ambiguity. Of the three options, only one stands out as plausible. As a result, we attributed this inference to the author, and analyzed the argument accordingly. It is important to note that in saying that Option #3 stands out as the most plausible, we are not thereby saying that we agree with the author or think the argument is sound. Rather, we are engaging cooperatively with the text (see Chapter 2). We are assuming that the author is a reasonable person, and we are trying to interpret the argument in a way that is fair to them. For all this, we might still be skeptical of, or disagree with, the argument.

It is worth noting that we do this sort of thing all the time. The way we deal with typos is a good example. To illustrate, imagine you get a text from you mom that says: ‘can you get some nilk at the store’. You will automatically assume that she meant ‘milk’. Why? Well, you’ve never heard of a product called ‘nilk’, milk, on the other hand, is something you buy regularly, and it would be easy to hit an ‘n’ instead of a ‘m’. Thus, like the case above, in this instance you’ve used your knowledge and experience to look behind what somebody has said and identify their likely intention.

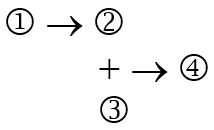

Let us return to the analysis. We have resolved the ambiguity, and we have the main reasons for the conclusion. The next step is to ask about second-level reasons, and we saw above that the author gives one for thinking that Martinez’s statistics weren’t earned (namely, that he used performance-enhancing drugs). We have captured the whole argument, and we can standardize and diagram Ex. 6 as follows:

- Martinez took performance enhancing drugs

- So, Martinez’s batting statistics weren’t earned. (from 1)

- Martinez was a divisive figure who undercut the success of his teams.

- So, there is no room in the hall of fame for Jack Martinez. (from 2 and 3)

Again, what is important about this example is the cooperative approach to ambiguity. We were not sure where to put the last claim, and in order to figure it out we considered the possibilities, and discovered that one, in particular, would make sense given that the author is a reasonable person who intends to give a strong argument. Put in slightly different terms, we proposed and tested several different possible analyses of the argument to ultimately arrive at a final analysis.

Before turning to the exercises, let’s briefly review the method we’ve been using. We’ll simply call it The Method.

The Method:

Step 1: Find the main conclusion by asking “what is the point of the piece?”

Step 2: Find the author’s main reasons by asking “what reasons does the author give for the main conclusion?” Resolve ambiguity by considering competing analyses.

Step 3: Find secondary reasons by asking: “does the author offer any evidence for the main reasons?” Resolve ambiguity by considering competing analyses.

Step 4: Find tertiary reasons by asking: “does the author give any evidence for the secondary reasons?” Resolve ambiguity by considering competing analyses.

Step 5: Continue this process until the answer is ‘no’.

As a final note, The Method is a tool for comprehensively analyzing an argument. That is, consistently applying this technique to an argument will allow you to see every (stated) element of an argument. It is important to point out, however, that we do not always want or need to go to such depth. Particularly when it comes to longer texts. Depending on our interest or the situation at hand, we may only need to identify the conclusion and the author’s main reasons. Alternatively, we may be primarily interested in one of the sub-arguments and only need to analyze a part of the argument. In general, different interests or concerns call for different degrees of analysis. We will say more about this in Chapter 6. For now, however, we will practice fully applying the method and comprehensively analyzing arguments.

Exercises

Exercise Set 4A:

Directions: Determine whether ‘because’ is being used in an evidential sense or an explanatory sense.

#1:

You and your roommate walk into your dorm room; you flip the light switch and the light does not come on. Your roommate says: “the light didn’t come on because the bulb is burned out.”

#2:

The Broncos are likely to be in the championship hunt this year because of their offseason talent acquisitions.

#3:

A bank manager and her employees watch as the new vault door fails to close. At which point the repairperson says, “The door to the bank vault doesn’t work correctly because it was not built with hinges strong enough to carry the weight of the door itself.”

#4:

Fewer people will be flying this summer because of the recent spike in ticket prices driven by a surge in the price of jet fuel.

#5:

You limp into the doctor’s office, and tell the nurse: “I hurt my ankle because I was wearing the wrong shoes”.

Exercise Set 4B:

Directions: For each of the following determine whether the passage contains an argument. If it does not, write “no argument”. If it does, then standardize and diagram the argument.

#1:

You don’t have to worry about giving me the chicken pox. I’ve already had it.

#2:

The fact that the candidate only paid an effective tax rate of 15% in the last couple of years is distressing, but is it relevant to his candidacy for president? No way. It is not like he set the tax rate; he paid what he owed just like the rest of us.

#3:

Nearly two years after the catastrophic Equifax data breach of 2017 was announced, it looks like the company is readying to cough up damages to any of the 147 million people whose personal information was exposed in the breach.

#4:

The claim that the U.S. cannot afford to put a cap and price on greenhouse gases is mistaken. It costs less than many other government programs. Moreover, the cost to households, according to the Congressional Budget Office, would be small. Last, a good program would create more jobs than it cost.

#5:

Unemployment continued to fall in the second quarter largely because of a construction boom in the Sun Belt.

#6:

Headline: “Sculpture bears little resemblance to Kings”

The Jan. 19 issue of the newspaper had a picture of the new Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King statue. Perhaps the city should have second thoughts about the purchase. The sculpture looks nothing like them. No likeness at all! It is not a fitting monument to them.

#7:

This governor has got to go! He doesn’t have a clue–he actually thinks that the way to drive students to achieve is to buy new computers for our schools. You only have to look at the statistics to see that poverty is the obvious cause of educational under-achievement. Eighty percent of those who ultimately drop out come from homes whose income is at least 50 percent below the average.

#8:

Because virtually all states award all their electoral votes to the winner of the popular vote in the state, and because the Electoral College weighs the less populous states more heavily, it is entirely possible for the winner of the electoral vote to lose the popular vote.

#9:

An attorney says to a potential client: “I would not recommend going forward with your suit against the mayor for defamation for two reasons. First, there is a good case to be made that the mayor’s remarks about you were privileged. Given this, they cannot be the basis for a defamation suit. Second, you admit that the mayor’s remarks about you are, strictly speaking, true. This means that, legally speaking, you have not been defamed, since defamation only applies when statements about a person are false.”

#10:

According to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, more than 1 billion people in the world are hungry and about 25,000 people die every day from hunger or related causes. The United Nations estimates the cost of ending world hunger at $195 billion a year. That sum — $195 billion — is a lot of money. However, the world military expenditure was $1.46 trillion in 2008, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. The Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation credits the U.S. military having spent $660 billion or 43 percent of the total world expenditure for military purposes in 2007. How have our priorities become so disordered?