Argument Analysis

6 Argument Analysis–Some Final Notes

Section 1: Introduction

We have looked at some of the most significant complications to the process of argument analysis. In this chapter, we will consider a number of other important considerations, and bring all of our skills together. We will start by distinguishing independent from conjoined premises, noting the difference between arguments and reports of arguments, and discusssing peripheral information. We will close this chapter by putting our skills to work on a much longer, but more realistic, text.

Section 2: Conjoined verses Independent Premises

Authors will sometimes offer multiple distinct arguments on behalf of a single conclusion. Consider the following example:

Ex. 1:

You shouldn’t go this weekend because you can’t afford it. But even if you could afford it, you shouldn’t go because Laila will be there.

We might be tempted to give a surface-level analysis of this example as follows:

Standardization of Ex. 1?

- You can’t afford to go.

- Laila will be there.

- So, you shouldn’t go.

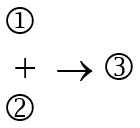

Diagram of Ex. 1?

However, neither of these representations accurately reflect the argument’s structure. The reason is that the author is not claiming that 1 conjoined with 2 shows or establishes 3. The author’s claim is that 1 all by itself establishes 3; that is, the fact that you can’t afford to go, means that you shouldn’t go. Similarly, the author is claiming that 2 all by itself establishes 3. We know this because the author explicitly tells us that even if you could afford to go (that is, even if 1 were false), it would still follow that you shouldn’t go since Laila will be there.

Given that the author takes these reasons to independently show the conclusion, we have two distinct arguments. This needs to be reflected in our analysis of the argument, and we will do so in the standardization by explicitly saying this after the conclusion:

- You can’t afford to go.

- Laila will be there.

- So, you shouldn’t go. (from 1 and 2 independently).

In addition, let’s agree to represent this kind of argument using a diagram as follows:

Diagram of Ex. 1:

Authors are not always explicit about how the premises of an argument are related to the conclusion. Imagine the person in Ex. 1 has said something slightly different, call it Ex. 1*.

Ex. 1*:

You shouldn’t go this weekend because you can’t afford it. Also you shouldn’t go because Laila will be there.

Put in this way, the argument’s structure is not obvious. Does the author mean for the premises to be taken together or independently? More generally, how should we represent an author’s argument when it is ambiguous in this way? In order to deal with this situation, we will adopt the following rule:

Rule for Independent Premises: When multiple reasons are offered on behalf of a single conclusion we will assume that the author intends all the premises to be taken together, unless the author explicitly says otherwise.

Why adopt this rule? On the one hand, this rule makes sense because arguments with independent premises are much less common than arguments with conjoined premises. In addition, there is no harm in reading ambiguous arguments as having conjoined premises, since doing so captures the author’s main point in offering the argument in the first place, namely that we should believe the conclusion on the basis of the premises. Interpreting ambiguous arguments as having independent premises, on the other hand, opens to the door to misinterpretation, since it treats each premise, all by itself, as sufficient for the conclusion. While the author may mean this, they may not. For these reasons, then, we will always interpret ambiguous arguments like this as having conjoined premises unless the author explicitly tells us they mean otherwise.

Finally, we should briefly consider what deep analysis looks like in cases of independent premises. Since there are two inferences here, there is the possibility of two argumentative gaps, and indeed this is the case in Ex. 1. First, there is a gap between the fact that the person can’t afford to go, and the conclusion that she shouldn’t go. Second, there is a gap between the fact that Laila will be there, and the conclusion that she shouldn’t go. How are these distinct propositions supposedly related? In order to identify the missing premises here, we need to identify propositions that plausibly bridge the gap by including the contents of both the premise and the conclusion. Thus, we might end up with the following:

(MP): You shouldn’t do things that you can’t afford to do.

(MP): You shouldn’t go to places that Laila will be.

Remember, missing premises are added to existing premises, and we can include these missing premises in our standardization by assigning them a number, and modifying the justifications as follows:

- You can’t afford to go.

- You shouldn’t do things that you can’t afford to do. (MP)

- Laila will be there.

- You shouldn’t go to places that Laila will be. (MP)

- So, you shouldn’t go. (from 1 and 2, and 3 and 4, independently).

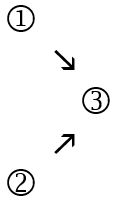

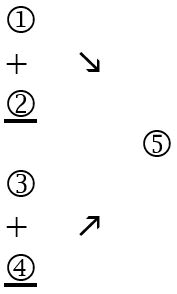

Here is the diagram for this example:

Again, we have underlined 2 and 4 to indicate on our diagram that these are not stated premises, but are being attributed to the author.

Section 3: Peripheral Information

So far in this unit we have practiced our argument analysis skills on short texts. However, there is a sense in which this isn’t very realistic. Almost everything we read or listen to in everyday life is much longer, and comes embedded within a larger context. As such, it is important to be able to distinguish the arguments from the context. We will use the term peripheral information to identify information that is presented within the context of an argument, but which is not part of the author’s main argument. To be clear, saying that some piece of information is peripheral to the argument is to say only that it is does not figure into the argument as a premise or a conclusion, and so should not be included in an analysis of the main argument. A peripheral claim may, nevertheless, be very important for understanding the significance of an argument, its history, its motivation, or any of a number of other background features. Let us look at an example.

Ex. #2:

For decades the city has funded three public golf courses. Roosevelt Park Golf course opened in 1925, while Kasten Park opened in 1959, and Westfield in 1991. Unlike private country clubs, anyone is eligible to play on these courses, and there are reduced rates for young people, senior citizens, and military veterans. In recent weeks, the city council has opened up the future of these courses to public discussion, and I’d like to be the first to propose closing the Westfield course. Westfield is the least popular course and it will cost the city at least 2 million dollars to make repairs after last summer’s flooding. Moreover, the land this golf course occupies could better serve the residents of the city as a general use park.

We do not get to the author’s argument until about halfway through this paragraph. The author’s point in this passage is that the city should close Westfield golf course, and she gives a number of reasons for it. The rest of the information in this paragraph is peripheral. The names of each of the public courses and the dates they opened may be important for appreciating the argument, but this information is not being used as evidence for the main conclusion that Westfield course should be closed.

In general, distinguishing the argument from peripheral information is not too difficult if you are using The Method. Recall that according to this method, we should start with the main conclusion and methodically work backwards to identify the all argument’s premises. Once we’ve completed that process, we will have uncovered the main argument, and consequently, everything that is left will be peripheral. Nonetheless, there are two kinds of peripheral information that can be tricky: qualifications and replies to objections. Let’s start with qualifications.

Often authors will stop to qualify or clarify their claims. Indeed, qualification and clarification are signs of a well thought-out argument. Imagine, for example, that the author of Ex. 2 above continues:

Ex. #3:

I realize that there are residents that enjoy playing regularly at Westfield, and I am not saying that the course is of no service to the community. I am saying only that there are better ways for the city to use this land.

This is an important part of the argument. The author is telling us that she recognizes that the course is a valuable public service. He has taken this into account, and should not be understood as saying Westfield is of no service. Because qualifications like this can tell us something important about the argument, it can be tempting to include them in the standardization. Nevertheless, we should not. Although qualifications and clarifications can be helpful for understanding an argument, they are not themselves a premise or conclusion, and so should be left out of an analysis.

A related situation occurs when an author pauses in the middle of their argument to answer or reply to an objection. In cases like this, the author foresees an objection and wants to cut it off or eliminate it in the audience’s mind before proceeding with the rest of the argument. In the following example, the Asst. Manager of a shoe store is talking to the Manager.

Ex. #4:

I think the store should once again carry Campx brand boots. We have had several requests about them over the last few weeks, and they offer a distinctive product. It’s true that we stopped carrying them in the past due to problems with product quality, but the company is under new management and claims to have addressed these issues. One other thing: the company is about to kick off a multi-million dollar ad campaign which will surely drive greater interest in these boots.

The assistant manager is arguing that the store should carry Campx brand boots. However, he foresees that the manager might object on the grounds that they’ve had problems with Campx products in the past. The author raises this objection and then offers a counter-argument. What can be tricky about this kind of case is that though the author is offering an argument, it is not part of the main argument. The reply is a distinct argument, and so is peripheral to the main argument.

Section 4: Distinguishing Arguments from Reports of Arguments

Argument reports are common in everyday communication. To report an argument is to describe somebody else’s argument. It is important not to confuse a case in which an author reports an argument with a case in which an author puts forth an argument they endorse. Certainly a person can report an argument that they endorse; nevertheless, this need not be the case. Here is an example:

Ex. #5:

Kylie says she isn’t going to register for a Film Studies course this semester because she is already enrolled in too many courses.

This is not an argument. In this case, the author is not making any claims about Kylie’s argument, but is simple reporting Kylie’s thought process. Although a report is not, in itself, an argument, reports can be parts of arguments. In fact, any time we argue against somebody else’s argument we report it (after all, we have to say what we are objecting to). Consider this case from a newspaper editorial:

Ex. #6:

I read Wes Pauling’s Jan. 13 column, ”The death penalty can be justified,” hoping for insights, but his argument lacked proof. Pauling says that the absence of the death penalty makes violent criminals more prone to excesses because they know they will not face death. While this sounds reasonable, few criminals weigh the penalties they face if convicted. Most are unaware of legal consequences, do not care, or feel they will never be caught.

In this example, the author’s conclusion is that Wes Pauling’s argument lacks proof. As part of his evidence for this proposition the author offers a report of Pauling’s argument (“Pauling says…”) and his reason for thinking this argument is poor.

Section 5: Analyzing a Longer Piece—Stage 1 and 2 of The Method

In this last section, we will put our skills to work on a longer, and more realistic, example. The process of analyzing the main argument in a longer text using The Method is the same as a shorter case. Thus, the first step is to read through the passage and identify the main conclusion. Nevertheless, in a longer case, there is more information to keep track of, and so we will need to be very organized. Let’s turn to the example.

Ex. #7: “The Age of Twitter” by Brian L. Ott

Twitter is a microblogging platform—a form of blogging in which entries typically consist of short content such as phrases, quick comments, images, or links to videos. Users send and receive “tweets,” messages consisting of no more than 140 characters. Since its launch in March 2006, Twitter has grown rapidly in popularity, and by 2014, it had more than 500 million users.

Different communication technologies shape how users process information and make sense of the world, and Twitter is no different. However, Twitter is different in that it has an especially toxic effect on public discourse. I’m not suggesting, of course, that all content on Twitter is harmful. Much of the Twittersphere is relatively innocuous. The danger comes when issues of social, cultural, and political import are filtered through the lens of Twitter.

Twitter negatively influences the public discourse in three ways I will point out. First, because of its 140 character limitation, Twitter structurally disallows the communication of detailed and sophisticated messages. This isn’t to say that a Tweet can’t be clever or witty—it can, but overall Twitter is not a medium for communicating complex thoughts. Second, tweeting is a highly impulsive activity that one can do even if one has nothing considered or important to say. Using this platform requires almost no effort at all—one can tweet from virtually anywhere at any time with the push of a button. The last point is that Twitter encourages uncivil discourse. Twitter’s lack of concern with proper grammar and style undermines norms that tend to enforce civility. Further, Twitter “depersonalizes interactions” creating a context in which people do not consider how their interactions will affect others.

In our society we have seen the rise and mainstreaming of divisive and incendiary public discourse, and a growing intolerance for cultural and political difference over the last 10-15 years. It is difficult to say how much of this is a consequence of Twitter, but one thing is certain: the continued use of Twitter as a means of communicating important ideas will not help matters.[1]

What is the main point of this piece? Overall, the author is critical of Twitter, but he seems to draw two conclusions about it. First, he tells us in the second paragraph that Twitter “has an especially toxic effect on public discourse,” and then proceeds to give three reasons on behalf of this proposition. Second, he brings the piece to a close by concluding: “the continued use of Twitter…will not help” to fix the growing intolerance for cultural and political difference in public discourse. Which one is the main conclusion? The propositions seem to be related, and this suggests one is being given as a reason for the other. This presents us with two options to compare:

- Option #1: The author is claiming that the fact that Twitter has an especially toxic effect on public discourse is a good reason to believe that the continued use of Twitter will not help fix the problems in public discourse.

OR

- Option #2: The author is claiming that the fact that the continued use of Twitter will not help fix the problems in public discourse is a good reason to believe that Twitter has an especially toxic effect on public discourse.

When set out this way, Option #1 is clearly preferable. While we might not agree with the argument expressed in Option #1, it is an argument one could reasonably make. Option #2, in contrast, is hard to understand, and is consequently less plausible to attribute to a reasonable interlocutor than Option #1. Given this, we’ve identified the main conclusion, and at least one of the author’s main reasons.

In order to illustrate the process of analyzing this longer piece, we will forgo numbers until the end. Instead we will follow the terminology outlined in The Method of ‘main reasons’, ‘second-level reasons,’ ‘third-level reasons,’ and so forth. Accordingly, we will call the proposition Twitter has an especially toxic effect on public discourse, Main Reason #1, or MR1 for short. It doesn’t look like the author offers any other main reasons, so we will proceed to the next step of analysis.

MR1: Twitter has an especially toxic effect on public discourse

MC: The continued use of Twitter as a means of communicating important ideas will not help matters.

Section 6: Analyzing a Longer Piece—Later Steps of The Method

Before continuing it is worth reminding ourselves that we do not always need to comprehensively analyze an argument. As we noted at the end of Chapter 4, different degrees of analysis are appropriate for different situations. In some cases, we may only need or be concerned with the conclusion and the author’s main reasons for thinking it is true. In such a case we need not go through the work to identify secondary or tertiary sets of reasons. Alternatively, we might only be interested in a specific sub-argument at work in the piece, and so not need to reconstruct the whole thing.

Indeed, in everyday life the need or interest to comprehensively analyze lengthy arguments like this is rare. For example, in the “Age of Twitter” the author makes the provocative claim that Twitter has an especially toxic effect on public discourse, and we might only (or primarily) be interested in his main reasons for thinking this is true. Nevertheless, we will go ahead with a comprehensive analysis in this case in order to illustrate larger argumentative structures as well as to illustrate some of the interpretive situations and techniques discussed in this Unit.

Ok, so we have identified the main conclusion and the author’s main reason for thinking it is true (MR1). The next step is to ask whether the author provides any evidence for MR1. In this passage, the author is very direct about this. He says: “Twitter negatively influences the public discourse in three ways I will point out,” and proceeds to give three reasons labeling them ‘first,’ ‘second,’ and ‘third,’. Thus, we know the second-level reasons, or SRs, on behalf of MR1 are as follows:

SR1: Twitter structurally disallows the communication of detailed and sophisticated messages.

SR2: Tweeting is, then, a highly impulsive activity that one can do even if one has nothing considered or important to say.

SR3: Twitter encourages uncivil discourse.

We now need to investigate each second-level reason. Does the author offer any evidence on their behalf? Let’s begin with SR1. The author gives us a reason for SR1 when he says: “because of its 140-character limitation, Twitter structurally disallows the communication of detailed and sophisticated messages.” We thus have a third-level reason, call it, TR1, for SR1.

TR1: Twitter has a 140-character limit.

The author continues, saying “This isn’t to say that a Tweet can’t be clever or witty—it can, but overall Twitter is not a medium for communicating complex thoughts.” Here the author is being careful to note that the 140-character limit is not all bad, and then reiterates SR1 in slightly different terms. Since he is repeating himself, we don’t need to include this in our analysis.

Let’s turn to SR2: “Tweeting is a highly impulsive activity that one can do even if one has nothing considered or important to say.” Does the author give any evidence on behalf of this proposition? He follows SR2 by saying:

“Using this platform requires almost no effort at all—one can tweet from virtually anywhere at any time with the push of a button.”

He does not use an indicator word, but the proposition “Using [Twitter] requires almost no effort at all” does support the claim in SR2 that it is an impulsive activity. Given this, and that the proposition immediately follows SR2, the author is likely offering evidence for SR2 here. Furthermore, though he doesn’t use an indicator word, he offers evidence that using the platform is easy in saying that “one can tweet from virtually anywhere at any time with the push of a button.” Thus, we are given a third-level reason for SR2, call it TR2, and then given a fourth-level reason for TR2, call it FR1.

FR1: One can tweet from virtually anywhere at any time with the push of a button.

TR2: Using this platform requires almost no effort at all.

We have been working backwards through the layers of this argument, and have considered the reasons the author offers on behalf of two of his second-level reasons. One remains: SR3. Does the author give us any reason to believe SR3? Yes, he gives two reasons, saying:

Twitter’s lack of concern with proper grammar and style undermines norms that tend to enforce civility. Further, Twitter “depersonalizes interactions” creating a context in which people do not consider how their interactions will affect others. We’ll call these two reasons third-level reasons 3 and 4 (or TR3 and TR4).

TR3: Twitter’s lack of concern with proper grammar and style undermines norms that tend to enforce civility.

TR4: Twitter “depersonalizes interactions” creating a context in which people do not consider how their interactions will affect others.

Ok, next step: does the author give us any reason to believe TR1-4? We’ve already seen that he gives one reason for TR2, which we called FR1, but when we ask whether the author has given us any reason to believe that any of these other third-order reasons are true, the answer is ‘no’. This means that we are done with our Surface-Level Analysis. Let’s go ahead and reorder them.

TR1: Twitter has a 140-character limit.

SR1: So, Twitter structurally disallows the communication of detailed and sophisticated messages. (from TR1)

FR1: One can tweet from virtually anywhere at any time with the push of a button.

TR2: So, using this platform requires almost no effort at all. (from QR1)

SR2: So, tweeting is a highly impulsive activity that one can do even if one has nothing considered or important to say. (from TR2)

TR3: Twitter’s lack of concern with proper grammar and style undermines norms that tend to enforce civility.

TR4: Twitter “depersonalizes interactions” creating a context in which people do not consider how their interactions will affect others.

SR3: So, Twitter encourages uncivil discourse. (from TR3 and 4)

MR1: So, Twitter has an especially toxic effect on public discourse. (from SR1-3)

MC: So, the continued use of Twitter as a means of communicating important ideas will not help matters. (from MR1)

Ordering the propositions in this way shows how we have followed The Method in analyzing this argument. Now that we have everything, however, we can add numbers for our final Surface-Level Analysis of Ex. 7:

- Twitter has a 140-character limit.

- So, Twitter structurally disallows the communication of detailed and sophisticated messages. (from 2)

- One can tweet from virtually anywhere at any time with the push of a button.

- So, using this platform requires almost no effort at all. (from 3)

- So, tweeting is a highly impulsive activity that one can do even if one has nothing considered or important to say. (from 4)

- Twitter’s lack of concern with proper grammar and style undermines norms that tend to enforce civility.

- Twitter “depersonalizes interactions” creating a context in which people do not consider how their interactions will affect others.

- So, Twitter encourages uncivil discourse. (from 6 and 7)

- So, Twitter has an especially toxic effect on public discourse. (from 2, 5, and 8)

- So, the continued use of Twitter as a means of communicating important ideas will not help matters. (from 9)

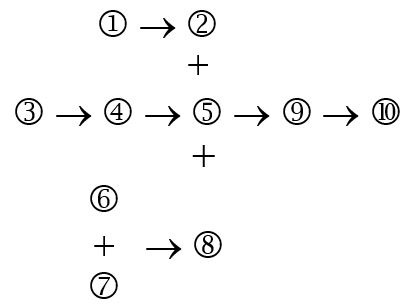

Surface-Level Diagram of Ex. 7:

A few final notes about this example are in order. First, this article contains a lot of peripheral information. As it turns out, the whole first paragraph is peripheral to the main argument. Second, the author raises and replies to an objection when he says “I’m not suggesting, of course, that all content on Twitter is harmful. Much of the Twittersphere is relatively innocuous.” However, this is not part of the main argument and so was not included in the analysis. The last point is that we have not added missing premises here. That is, we have not pursued a deep-analysis of this example (though we could have).

This brings us to the end of the unit on argument analysis. We have discussed how to identify arguments, and learned some techniques for representing them. Moreover, we have focused on spotting argumentative gaps, and have learned some strategies for identifying hidden or missing premises. This can be hard work, and it is important to emphasize that the recommendation here is not to standardize and diagram every argument that we run across. Doing so is not realistic. Rather, the hope is that as a result of having worked through this unit you are able to spot and pull apart arguments in a much more explicit, effective, and efficient way. More generally speaking, hopefully working through these exercises has shown you the argumentative structures that underlie a lot of our everyday communication. We will continue to use our argument analysis skills as we proceed throughout the rest of the text, and in the next unit we will see more clearly the role analysis plays in the process of argument evaluation.

Exercises

Exercise Set 6A

Directions: For each of the following determine whether the passage contains an argument. If it does not, write “no argument”. If it does, then standardize and diagram the argument making sure to add missing premises. Also make a note of any reports or objections/responses the texts contain.

#1:

Did you know the music department has a course on Avant Garde music? I am definitely taking it next time it is offered. Given that you want to take the course too, you’ll have to sign up for Music Theory III next semester, since Music Theory III is a pre-requisite for taking the course.

#2:

According to Dept. of Justice officials, it isn’t realistic to think that Guantanamo prison will be closed this year since there just isn’t anywhere else to keep its current inmates.

#3:

A: I am sure I remember that the Mona Lisa is by Rembrandt.

B: No, you’re wrong.

A: I am pretty sure.

B: Look, the Mona Lisa was done in the early 1500s and Rembrandt lived during the 1600s. But suppose I am totally wrong about that. Even still, you are wrong since there is a picture of the Mona Lisa in this book about the works of Leonardo Da Vinci—see!

#4:

Smart growth — a politically convenient euphemism for increasing the density of residential neighborhoods and putting them nearer urban areas — is not an adequate solution. Most Americans clearly want more living space and countryside — not less, but even putting this aside, this solution fails since population density brings traffic–again, something nobody wants.

#5:

Parent to child: You know that you shouldn’t go to the concert. You promised me that if we didn’t give you a curfew any more, you would make sure that all of your homework was completed and submitted on time. And there is no way you can finish your history essay if you go to that concert. I know you are thinking that you can finish it, but c’mon you couldn’t finish the essay and have it be any good.

#6:

It is no wonder that Fox is pulling “Lone Star,” its acclaimed drama about a con man leading a double life. The show’s first episode was a Texas-sized bomb—only 4.1 million viewers showed up for the “Lone Star” premiere.

#7:

I will be voting in favor of the proposed bike-sharing program. There is significant community interest, it is not expensive to install, and has the potential to reduce traffic gridlock. Critics of this proposal claim that the municipality’s road and sidewalk system is not built for significant bike traffic, and they are right. However, the proposal introduces a limited number of bicycles, and according to officials from the police dept. this should not be a problem. One last benefit of this proposal is that it extends the reach of public transportation. A bike provides easy access to parts of the city not directly served by bus.

#8:

A British rabbi is encouraging couples to consider being buried on top of each other in single graves to save money and space in cemeteries. Rabbi Ian Morris, of Sinai Reform Synagogue in Leeds, suggested the idea in his newspaper. His argument was that we need to save land and double-depth burials will do that.

#9:

The idea that Iran is a threat to the U.S. itself is not credible. The Iranians do not have the capacity, technological or otherwise, to strike the U.S. in any meaningful way. But even putting that aside, it makes no sense for them to actually attack the U.S., since a U.S. response would be so devastating. Not only is there a carrier fleet just off their coast, but the whole country is virtually encircled by U.S. military installations in Iraq, Turkey, Afghanistan and elsewhere.

Exercise Set 6B: More Difficult Analyses

Directions: Standardize and diagram the following arguments making sure to add missing premises.

#10:

Chicago’s subway system, the “L”, is one of America’s oldest and busiest. The oldest portions of the system date to the 1890’s. Despite this history, the system in Chicago is atrocious. The “L” extremely loud, dirty, and inefficient (it takes forever to get from downtown to either airport). Not only that, but it doesn’t provide service to some of Chicago’s most important sites. Backers of the L argue that it can’t be that bad since the number of people using the system has remained stable over the last 10 years, but the fact the people are using the system doesn’t mean it is a good one! If we want Chicago to become a world-class city, we’ll need a world-class subway system, this is why we should support an overhaul of the current system.

#11:

Southwest, the nation’s largest low-fare carrier, announced Monday it had agreed to purchase smaller discount carrier AirTran for $1.4 billion, to get a footprint in Atlanta, the world’s busiest airport, and expand its presence in airports in New York, Washington, Boston, and Baltimore. AirTran will be absorbed by Southwest and adopt Southwest’s policies, according to details of the $1.4 billion deal. The question that remains, however, is whether this merger—if approved—will benefit consumers. The answer is yes and no. On the one hand customers will likely benefit from expanded offerings, since Airtran serves many smaller cities that Southwest currently does not. On the other hand, it is likely that the merger will ultimately result in higher prices. Mergers create less competition in the market. Consequently, there will be less pressure on airlines to keep their fares down. While the proposed deal’s effects remain to be seen, it seems likely that this merger is a mixed bag for consumers.

#12:

Headline: “Proposed Change for Pennsylvania Electoral College Bad Idea”

The Republican leadership in the Pennsylvania Legislature has shown interest in scrapping the current Electoral College system—where the presidential candidate who wins the most votes in Pennsylvania gets all of Pennsylvania’s electoral votes—and replacing it with a system where there is competition for single electoral votes in each of the state’s 18 congressional districts. This is a bad idea.

Perhaps the deepest problem with this proposal lies in the fact that it builds the system on which electoral votes will be divided up in Pennsylvania on a rotten foundation. The proposal seeks to make Congressional districts the ground upon which presidential elections in Pennsylvania will be built, but Congressional districts throughout the state and the nation have been purposely designed, or gerrymandered, to kill off real competition between the political parties. As long as the core remains rotten, this plan to reform the Electoral College remains rotten too.

Moreover, if Pennsylvania turns to a system where Electoral College votes are chosen district by district, you will ensure that most of the state’s electoral votes will be determined before the race even begins. Consequently, of course, presidential candidates will spend neither time nor money campaigning where the outcome is pre-ordained; it makes no sense to use precious resources on done deals.

Finally, the argument for this change offered by Republicans in the Legislature just doesn’t make any sense. They claim that the system needs to change because presidential elections in Pennsylvania just aren’t competitive, but the evidence just doesn’t support the claim. While Barack Obama won here by about 10 percentage points in 2008, Al Gore won by less than 5 percent in 2000 and John Kerry less than 2 percent in 2004. Hardly evidence of a playing field on which Republicans can’t compete.

To be sure, the current version of the Electoral College has many liabilities. The winner-take-all system does not ensure that the candidate receiving the most popular votes will win the presidency. Al Gore can attest to that fact. It’s reasonable to explore options in which we as a people can have our voices heard in an equal and meaningful way. Unfortunately, this is not such an option. [2]

- Adapted from the article by Brian L. Ott (2017). “The age of Twitter: Donald J. Trump and the politics of debasement,” Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34:1, 59-68. ↵

- This example is significantly adapted from Borick, Christopher. (2011, Sept. 21). Proposed Change for Pa. Electoral College Rotten to the Core. Morning Call. https://www.mcall.com/opinion/mc-xpm-2011-09-21-mc-electoral-college-pa-borick-yv-0922-20110921-story.html. ↵