Argument Analysis

3 Analysis, Standardization, and Diagramming

Section 1: Introduction

In this unit, we will focus on argument identification and analysis. Argument identification involves spotting arguments and distinguishing them from their surroundings. We briefly discussed argument identification in Chapter 1, and saw that we need to be on the lookout for particular words (e.g. ‘since’, ‘so’, ‘because’, and ‘hence’) that frequently indicate the presence of an argument. The other skill we will focus on in this unit is argument analysis. In general, to analyze an argument is to determine its intended structure.

As we’ve seen, the crucial elements or “bones” of any argument are its premises and its conclusion, and we determine an argument’s structure by identifying these elements and figuring out how they fit together. We are beginning with the skills of identification and analysis in particular because recognizing and accurately determining argumentative structure are prerequisites for accurate evaluation. After all, we can’t assess whether an argument is good or bad until we know what the argument is supposed to be! More precisely, we can’t say whether an argument is sound or not, unless we know what its conclusion is, and what premises have been offered on its behalf.

Before we get started, it is important to make two notes. First, you are already skilled at argument identification and analysis. Again, these are prerequisites for evaluation, and you have been evaluating arguments almost your whole life. However, these skills are largely intuitive. The goal here, then, is not to develop new skills, but instead to sharpen or enhance existing ones. To this end, we will slow down and think through the steps involved in identification and analysis. By sensitizing ourselves to argumentative language in this way, we will make what is mostly implicit in everyday practice, explicit. More specifically, this will involve giving names to a variety of argumentative moves and situations, identifying a method for seeing behind an author’s words, and learning some techniques for representing arguments. Proceeding in this way will allow us to see in detail how arguments are expressed and structured, and will ultimately put us in a better position to evaluate and engage with arguments.

The second note has to do with reading. We will be focusing on arguments in text, and one of the things that we will find is that in all but the simplest cases, argument analysis requires active engagement with the text. We actively engage with a text when we ask questions of it: what is the author trying to say? What reasons does the author give for the conclusion? Why do they believe the premises are true? We do not always read actively. When we read a magazine or a novel, we normally sit back and let the author provide us with information or tell us a story. However, when it comes to argument analysis passive reading will not do. In most cases, argument analysis will involve actively looking to the text for clues, and using these clues to piece together the author’s intended argument. Active engagement with a text can be demanding—especially at first, but it is an important skill, and something you will likely find becomes easier with practice.

Section 2: Analyzing Simple Arguments

Let’s start with a simple argument.

Ex. 1:

Since Banana Republic’s sale items will go fast, I think we should go there first.

The first thing we should notice in this case is the word ‘since’. This word typically indicates the presence of an argument, and a look back at the context confirms this. Now that we have an argument, how do we analyze it? We need to break the argument into its components, i.e. its premises and conclusion. Because the word ‘since’ is not only an argument indicator, but a premise indicator, we know that what follows it—‘Banana Republic’s sale items will go fast’—is being used as a premise. This premise supports the proposition ‘we should go there first’ which is the conclusion. We have captured all there is to say about this argument’s structure, and so our analysis is complete.

Importantly, what makes this argument simple, as we will use the term, is not that it is short or easy to understand. Instead, this argument is simple because it draws only one conclusion. As we will see later in the chapter, simple arguments can be chained together to form complex arguments. For now, however, let us take a look at another simple argument.

Ex. 2:

The coach will likely be fired, given the allegations of unethical recruiting practices and the team’s sub-par performance the last three years.

The term ‘given’ and a quick look at the context tells us that we have an argument on our hands. ‘Given’ is a premise indicator, and in what immediately follows the author makes two claims. The author is claiming that there are allegations of unethical recruiting practices and that the team’s performance over the last three years has been sub-par. The author is offering these two premises as evidence for the proposition that the coach will likely be fired, and so this latter proposition is the conclusion.

This second example is similar to the first; however, we should note two important differences. First, in this example there are two premises, whereas in Ex. 1 there was only one. This does not change the fact that like Ex. 1, Ex. 2 is a simple argument. Again, what makes an argument simple is that it draws only one conclusion, and this means that simple arguments can have many premises. The second point has to do with order. In Ex. 1 the premise came first and the conclusion last, whereas in Ex. 2 the order is reversed. This teaches us an important lesson: premises are not always presented first, nor are conclusions always presented last. As it turns out, in everyday speech and writing, arguments are presented in many different ways. Sometimes, in fact, the conclusion is placed between premises (as we will see).

Section 3: Representing Argumentative Structure

The point of analyzing an argument is to uncover its structure, and it will be useful to have a uniform or standard way of representing the bones of an argument. For simple arguments we will use the following process of representation. For each distinct part of an argument (each of its premises and its conclusion), we will assign a unique number, assigning the highest number to the conclusion. We will then stack the propositions in numerical order, and add a conclusion indicator to the conclusion for clarity. We will call this way of representing an argument, a standardization.

In Ex.1, the argument consists in two propositions: the premise and conclusion, and so in our standardization we will stack the numbers 1) and 2). We will assign 2) to the conclusion, and then add the conclusion indicator ‘so’ to the argument. This gives us the following standardization of Ex. 1:

- Banana Republic’s sale items will go fast.

- So, we should go there first.

The argument in Ex. 2, consists of three propositions: two premises and the conclusion. As a consequence, our standardization will stack the numbers 1, 2, and 3, we will make 3 the conclusion, and add the indicator word ‘so’ to it. This gives us the following standardization for Ex. 2:

- There have been allegations of unethical recruiting practices.

- The team’s performance over the last three years has been sub-par.

- So, the coach will likely be fired.

Standardizing arguments is a useful way of representing an argument’s structure, but it is not the only way. A different way of representing the bones of an argument is called diagramming. Diagramming is a more abstract way of representing arguments that allows us to see an argument’s structure independently of its subject matter.

Just as we would in a standardization, we start a diagram by assigning each part of an argument a number. We start numbering at one and reserve the highest number for the conclusion. This is where the similarity ends, however. First, when diagramming, we let the assigned number stand in for the whole proposition; we do not rewrite the premises and conclusions as we do in standardizations. Second, when we diagram we will use numbers with circles around them to indicate propositions. Third, we will not stack the numbers, but work horizontally to capture the relation between the premise and conclusion. Doing so, requires the use of two additional symbols: the arrow (‘→’) represents the relationship between an argument’s premises and its conclusion. The arrow points away from the premises, and toward the conclusion the premises purport to establish. Further we will use the plus (‘+’). The + represents the idea that an author intends two or more distinct propositions to be taken together as evidence.

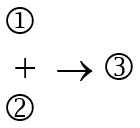

The diagram of Ex. 1 looks like this:

![]()

Thus, 1 represents the proposition ‘Banana Republic’s sale items will go fast’, while 2 represents the conclusion that ‘we should go there first’. Moreover, the arrow points from 1 to 2 because 1 is the evidence that purports to establish 2.

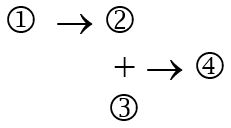

In the case of Ex. 2, the author offers two pieces of evidence on behalf of his conclusion. and this is reflected here by the conjunction of 1 and 2 (which represent the propositions that there are allegations of unethical recruiting practices and that the team’s performance over the last three years has been sub-par).

Diagram of Ex. 2:

It is important to note that standardization and diagramming are distinct ways of representing argumentative structure, and we can use one without the other. That is, we might standardize an argument without diagramming it, and vice versa (though if you choose to diagram an argument without also standardizing it, you’ll have to find a way connect your numbers to the propositions they represent). In this unit, however, we will always standardize and diagram examples, and we will use the numbers assigned in the standardization of an argument for the diagram. Now that we have discussed simple arguments, let’s see how analysis works in more complex cases.

Section 4: Analyzing Complex Arguments

A simple argument draws only one conclusion. However, simple arguments can be put together to create complex arguments. As we will see, complex arguments draw one or more sub-conclusions on the way to the main conclusion. Consider the following case:

Ex. 3:

You should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air for two reasons. First, nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls much more slowly than plain air, since nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen. Second, filling your tires with nitrogen keeps water vapor from getting inside your tires.

Uncovering the structure of this argument means isolating all of the parts and determining their relationships. We will begin by using indicator words as our guide. On a first pass, we should be struck by the presence of two indicators: ‘two reasons’ and ‘since’. The author is claiming that there are two reasons for thinking that “You should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air.” The author has numbered these premises using the term ‘first’ and ‘second’. Thus, these two propositions are premises that support the conclusion that you should put nitrogen in your tires. However, there is one other indicator word here—‘since’. This suggests that there is a second justification present. Indeed, the fact that “nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen” is given as a reason to believe that “nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls more slowly than plain air will.” This means the author’s claim that “nitrogen will diffuse…” is being used as both a premise and a conclusion. On the one hand, it is a premise because it supports the proposition that you should fill your tires with nitrogen. On the other, it is a conclusion because it is supported by the proposition that nitrogen molecules are bigger than oxygen molecules.

Our analysis is complete; we have uncovered all the parts of the argument and we know how they are related. In order to represent this argument’s structure let’s standardize it. As we learned above, we should assign a number to each relevant proposition reserving the highest number for the conclusion. Wait. There are two conclusions in this argument. Which one should we assign the highest number? We will reserve the highest number for the ultimate or main conclusion, which in this case is that “You should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air.” Can we simply assign numbers to the other propositions, and standardize the argument like this:

Standardization for Ex. 3?

- Nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls much more slowly than plain air.

- Nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen.

- Filling your tires with nitrogen keeps water vapor from getting inside your tires.

- So, you should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air.

No. While this standardization captures all the relevant propositions, it misses an important part of the argument’s structure. Although 1-3 all ultimately support the conclusion, they do not do so in the same way. The proposition that nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of air only supports the conclusion because it gives evidence for the proposition that nitrogen will diffuse more slowly than plain air. In other words, 2 only supports 4 through its support of 1; let’s say that 2 offers only indirect support of 4 whereas 1 and 3)offer direct support, and our representation of the argument needs to reflect this. This means that we’ll need to supplement our basic standardization process.

First, let’s follow the convention that conclusions always come after their premises, so we’ll want to assign the proposition ‘nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen’ a higher number than the proposition ‘nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls much more slowly than plain air’. Second, since the proposition ‘nitrogen will diffuse…’ is a conclusion, we should make it clear by adding an indicator word to our standardization. Last, when there are multiple inferences in an argument we need to know for sure what premises lead to what conclusion. To mark this, let us agree that after every conclusion we will note the premises from which the proposition is drawn. Following these additional rules gives us the following standardization:

Standardization for Ex. 3:

- Nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen.

- So, nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls much more slowly than plain air. (from 1)

- Filling your tires with nitrogen keeps water vapor from getting inside your tires.

- So, you should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air. (from 2 and 3)

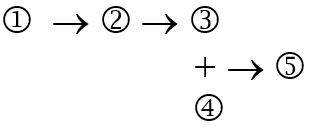

What does a diagram of Ex. 3 look like? We begin our diagrams with the conclusion. Following the number system we used in the correct standardization of Ex. 3, our main conclusion is 4, so we should start by drawing the number four with a circle around it. Evidence is offered on behalf of this conclusion, so we should draw an arrow to the left of our circled number pointing to it. What evidence is offered on behalf of 4? The propositions numbered 2) and 3) above are the direct evidence for 4), and we should connect these pieces of evidence using a plus since it is clear that the author intends these pieces of evidence to be taken together. Last, as we’ve seen, the author offers 1) as evidence for 2), so we should draw an arrow to the left of 2) pointing to it, and 1) to the left of that. This gives us the following diagram:

Diagram for Ex. 3:

The diagram of this argument shows very clearly that this complex argument is built out of two simple arguments. Working backwards from the main conclusion, there is the simple argument with 2 and 3 as premises and 4 as the conclusion. In addition, because the author gives a reason for 2, we have another simple argument from 1 to 2. Let us turn to some exercises.

Exercises

Exercise Set 3A:

Directions: For each of the following determine whether the passage contains an argument. If it does not, write “no argument”. If it does, then standardize and diagram the argument.

#1:

It seems likely that this year will be Morita’s first as a professional without a major win on account of continuing problems with her short game.

#2:

Your health care provider will not cover this test on the grounds that it is neither medically necessary nor an expense covered by your policy.

#3:

Disney was the first studio to release a truly massive film originally set for theaters onto a streaming platform. To watch their latest version of Mulan, viewers needed to pay close to $30 on top of their Disney+ subscription.

#4:

Judging from the astonishing range of daily life and human endeavor reflected in his poems and plays, we can only infer that Shakespeare was a keen observer.

#5:

You are not eligible for an upgrade, since you haven’t signed up for our newsletter, and signing up is necessary for eligibility.

#6:

Advisory boards are limited in authority, and consequently in legal responsibility, to those powers granted by the local government.

Exercise Set 3B:

Directions: For each of the following determine whether the passage contains an argument. If it does not, write “no argument”. If it does, then standardize and diagram the argument.

#1:

We can be sure that the murder was committed by the judge, given that it had to be either the butler or the judge, and we know it wasn’t the butler since he was passionately in love with the victim.

#2:

Since goat’s milk contains smaller fat globules than cow’s milk, it is easier to digest than cow’s milk. Consequently, goat’s milk may be a viable alternative for children who have a difficulty digesting cow’s milk.

#3:

To insert genes into a cell, scientists often prick it with a tiny glass pipette and inject a solution with the new DNA. The extra liquid and the pipette itself, however, can destroy it. In place of a pipette, scientists at BYU have developed a silicon lance. They apply a positive charge to the lance so that the negative charged DNA sticks. When the device enters a cell, the charge is reversed and the DNA is set free. In a recent study using this method, 72 percent of nearly 3,000 mouse eggs cells survived.[1]

#4:

The proposed ban on high-capacity magazines doesn’t make any sense. Think about it: a ban on high-capacity magazines wouldn’t necessarily prevent any of these mass killings, since with practice a person can learn to swap out a depleted 7 round magazine in a couple of seconds or less.

#5:

Because attention is a limited resource—we can attend to only 110 bits of information per second, or 173 billion bits in an average lifetime—our moment-by-moment choice of attentional targets determines, in a very real sense, the shape of our lives.[2]

#6:

The chief reason painting is superior to sculpture is that painting as a medium affords the artist many more possibilities than sculpture does. After all, how can you sculpt mist or clouds, or the appearance of reflective surfaces? Likewise, in painting the artist can represent impossible objects, and this is not an option for the sculptor who is bound by the laws of space and time.

Exercise Set 3C:

#1:

Make up a complex argument and write it out. Once you’ve done this, standardize and diagram your argument.

#2: Below is a standardized argument without any content. Draw the diagram that corresponds to this standardization.

1) xxxxxx

2) xxxxxx

3) So, xxxxxx (from 1 and 2)

4) So, xxxxxx (from 3)

5) So, xxxxxxx (from 4)

#3:

Below is an argument diagram. Create the standardization that corresponds to this diagram (don’t worry about content, just follow the xxxxx pattern from above).

#4:

What is a “rhetorical question”? Give an example. Can a rhetorical question be part of an argument?