Social Arguments

17 Trust and the Ad Hominem

Section 1: Introduction

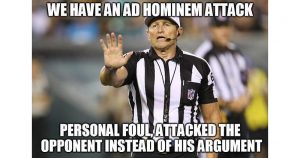

As we saw in the last chapter, our normal attitude toward the testimony of others is one of vigilant trust. That is, although we tend to accept what other people tell us, we are constantly on the lookout for signs of deception, insincerity, and incompetence. As we have seen, the fact that a person has something to gain or is somehow lacking in skill or expertise can give us a reason not to trust what they say. However, the fact that some features of a person can undermine the credibility of what they say, does not mean that they always do. This raises a number of questions: namely what features of a person undermine credibility, and under what circumstances? In this chapter we take up these questions. We will zero-in on arguments that appeal to some feature of a person to conclude that they are not credible. Arguments like this are called ad hominem arguments (Latin for “against the man”). Perhaps unsurprisingly, ad hominems are extremely common in everyday thinking. Of course, like other inductive argument forms, there are logically strong ad hominems and logically weak ones. Accordingly, in this chapter we will take a close look at how ad hominem arguments are used in everyday life, talk about what makes an ad hominem logically strong, and identify some strategies for accurate evaluation.

Section 2: To Trust or Not to Trust: Ad hominem Arguments

It is important to recognize that there are all kinds of conclusions we might draw about what a person has said based on what they are like, who they are, or what they have done. One common kind of inference appeals to what a person is like to draw a conclusion about their right to speak in some particular context. This is what we do when we say, for example: “since you aren’t part of the family, this is none of your business”. Similarly, when we say “people in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones” we are questioning the fairness or appropriateness of a comment. Neither of these are ad hominem arguments, however. What is distinctive about an ad hominem argument is that it is an inference from what a person is like to a conclusion about whether we can trust what they say in a particular case. As we have seen, our trust in a source is embodied in our assumption that they are both sincere and in a good position to have a true belief in this specific case. This is what we called The Credibility Assumption. Given this, we can define an ad hominem as follows:

An ad hominem argument draws a conclusion about The Credibility Assumption on the basis some feature of a source.

In principle, almost any feature of a person can serve as the foundation for an ad hominem argument; it is common for ad hominems to draw upon a person’s physical features, group membership (e.g. religion, class, political affiliation), achievements and failures, motives or interests, morality, and personal history (among many others). However, to say that these features can be used to challenge other people’s credibility is not to say that they actually do so. Again, as we will see there are both logically strong and logically weak ad hominems.

In addition, we can distinguish between positive and negative ad hominems. A positive ad hominem draws on some feature of the source as support for The Credibility Assumption, and to thereby bolster the importance of their testimony. Here is an example:

Ex. 1:

If you are in the market for a new car, I’d hold off until December. My aunt worked in car dealerships for 20 years, and always says the best time to buy a new car is at the end of the calendar year.

In this case, the speaker is treating his aunt as credible on this issue because of some feature of her—namely her decades in the car sales industry. In contrast, a negative ad hominem draws on some feature of the source to raise doubt about The Credibility Assumption, and to thereby dismiss or set aside their testimony. For example, the cases from Section 4 of the last chapter are all examples of ad hominem arguments:

Ex. 2:

We cannot simply take Isabel’s word for it that she saw Max leaving Ethan’s around the time of the murder, since she has a motive to lie.

The author here is concluding that we cannot accept Isabel’s testimony because of some feature of her—namely that she has a motive to lie. While we sometimes use positive ad hominems, negative ad hominems are much more common. Consequently, in the rest of this chapter we will focus on negative ad hominems.

Section 3: Negative Ad Hominems

Let us begin our discussion of negative ad hominems with some examples.

Ex. 3:

Taylor: Don’t worry. The CEO promises that Company A will never sell customers’ email addresses.

Cho: You can’t take her word for it; she made the same promise when she was working for Company B and it turned out that Company B was selling customer’s information as soon as it got it!

In this example, Cho gives an ad hominem that challenges the credibility of the CEO. He argues that we cannot take the CEO’s claim for granted because of a feature of the CEO, namely that she has broken similar promises in the past. Let’s take a look at another example.

Ex. 4:

Lara: I think pot should be legalized, I mean there is no good reason for legally distinguishing between alcohol and marijuana.

Ryan: You love smoking weed. Of course that’s what you think.

This is also an ad hominem, but Ryan’s argument is not nearly as clear as Cho’s was above. Ryan is attacking Lara’s credibility on this issue on the grounds that she loves smoking weed. He seems to be questioning Lara’s objectivity: she can’t think about the issue of legalization clearly because she has a clear preference. Moreover, he doesn’t come right out and conclude that “we can’t take her word for it.” Instead he insinuates that we cannot trust her by dismissing her claim, and this is common in ad hominems.

In the effort to identify ad hominem arguments, it is important to remember that not every argument that appeals to a feature of a person is an ad hominem. Consider the following example:

Ex. 5:

Brandon: E. M. Waterhouse claims that we would all be better off if we lowered the tax rate on millionaires.

Omar: That’s not true—I mean this is coming from a guy who is a millionaire himself!

Omar’s argument in this example is not an ad hominem, although it certainly looks like one. Omar is appealing to a feature of E.M. Waterhouse, namely that he is a millionaire, in order to criticize his claim. However, he is not challenging his credibility. Instead she claims that what Waterhouse says is false (he says, “that’s not true”). We will call this kind of argument, a denier, since they deny what the speaker has said.[1] That is, a denier uses a feature of a person to conclude that what they’ve said is false or incorrect. In contrast, ad hominem arguments only challenge a source’s credibility—they do not conclude that what the speaker says is false or incorrect (thought it might be). It is important not to confuse ad hominems and deniers, since deniers are almost never logically strong. That is, a feature of a person rarely offers sufficient evidence for thinking that what a person has said is false.

Not only can negative ad hominems draw different kinds of conclusions, but they can draw conclusions about the credibility of different subjects. In general, people draw ad hominem conclusions about three kinds of communication. On the most basic level, an ad hominem can draw a conclusion about a person’s credibility with respect to a specific claim (see Ex. 1, 2, and 3). Second, an ad hominem can draw a conclusion about a person’s credibility with respect to an argument (as is the case in Ex. 4). Last, we can draw conclusions about a person’s credibility when it comes to more substantial productions, e.g. a speech, article, book, or movie. For example:

Ex. 6:

I wouldn’t trust anything you see in that so-called “documentary”; the director is a well-known conservative activist.

The speaker in this case is giving an ad hominem which does not target any specific claim or argument, but challenges the credibility of the documentary as a whole based on the director’s political activity. Thus, negative ad hominems come in many different forms. They are often stated in somewhat ambiguous terms, and can target different forms of communication. Moreover, it is important to distinguish ad hominems from a similar form we’ve called Deniers. Suppose we’ve done that: we have spotted an ad hominem. What now? How do we evaluate it?

Section 4: Evaluating Negative Ad Hominem Arguments

As we have said, negative ad hominems all point to some feature of the source to challenge The Credibility Assumption. Again, the credibility of a source is embodied in our trust in its honesty, and our trust that the source is in a position to have an accurate belief. Thus, any feature of a person that gives good reason to doubt either of these conditions, thereby gives reason to doubt the source’s credibility. To evaluate an ad hominem, then, is simply to ask whether the feature in question gives us a reason to doubt either of these conditions. In Ex. 4 above, Cho gives a logically strong ad hominem: the fact that the CEO has failed to fulfill similar promises in the past calls into question her honesty in this case. In contrast, suppose Cho had responded this way:

Ex. 7:

Taylor: Don’t worry. The CEO promises that Company A will never sell customers’ email addresses.

Cho: You can’t take her word for it; she has been married three times!

Having been married three times does not give us a reason to think that the CEO is not being honest, nor does it give evidence that the CEO is not in a position to have accurate beliefs about this issue. Consequently, Cho’s ad hominem in this case would be logically weak. In general, to conclude that there is good reason to doubt a source’s credibility is to conclude only that the source’s testimony—all by itself—does not give us enough reason to believe what they have said. Again, to draw this conclusion is not to say they are wrong or mistaken. It is simply to refuse to take their word for it, and to agree to wait for more evidence before making a decision one way or another.

The fact that ad hominems can have different targets introduces a complication to the process of evaluating for logical strength. In order to illustrate the issue, consider the following two arguments. One is logically strong, and the other is not. Before reading on, see if you can distinguish the two.

Ex. 8:

Mike: The salesman says that the previous owner of this car was a little old lady who only drove the car to church on Sundays.

Ali: This guy earns a commission if we buy the car, so I am not just going to take his word for it.

Ex. 9:

TV News analyst: Mega Petroleum argues on the basis of the 1990 Oil Pollution Act that they are only legally responsible for paying 75 million in damages for the oil spill. We should be skeptical, however, since of course they want to avoid paying for the clean-up.

The crucial difference between these two cases has to do with the target of the ad hominem. In Ex. 8 Ali is questioning the credibility of the car salesman with respect to his claim that the previous owner was a little old lady. In Ex. 9, on the other hand, the analyst is challenging the credibility of Mega Petroleum with respect to their argument. This matters because when a person simply makes a claim, they are asking you to take their word for it. In contrast, when a person gives an argument, they are not. Rather they are appealing to evidence that they take to justify the conclusion, and this evidence will either stand or fall independent of their credibility or reliability.

The practical consequence of this is that, in most cases, to use an ad hominem against an argument is to violate The Rule of Total Evidence. Recall that according to this rule we are required, in formulating a conclusion, to take all the available evidence into account. When a person uses an ad hominem to draw a conclusion about an argument they ignore relevant evidence. Consider Ex. 9 above. The analyst in this case is skeptical of Mega Petroleum’s claim that they are only responsible for paying 75 million in damages. This makes sense given that Mega Petroleum clearly has an interest in this matter. However, Mega Petroleum has offered an argument for this claim. They are not asking us to trust them, but have presented independent evidence on behalf of this claim. Thus, given The Rule of Total Evidence we must take this argument into account if we want to draw a conclusion about the claim that they are only legally liable for 75 million in damages.

The upshot is that if we want to express skepticism about Mega Petroleum’s conclusion, we have to suggest that there is something wrong with the argument by challenging either its factual correctness or logical strength. The analyst in Ex. 9 has completely ignored Mega Petroleum’s argument by drawing the conclusion solely on the basis of the company’s interest in paying only 75 million. As with most inductive arguments, there are exceptions. For example, if a person offers an argument the premises of which rely on the credibility of the person, one might have a logically strong ad hominem for an argument. Nonetheless, most ad hominems when applied to arguments violate The Rule of Total Evidence.

In closing this chapter is it important to point out how useful ad hominem arguments are. They can help us know when we ought to ask more questions, as well as guide us to more reliable sources (among other things). Similarly, if a person has a history of exaggerating, then it makes perfect sense to doubt her claim that she saw “like 100 whales” on her vacation. So too when the mechanic says you need 4 new tires instead of just 1, you could just take his word for it. But if he has an interest in your buying 4 new tires you should be skeptical on the basis of an ad hominem and ask for more information.

Ad hominems are also useful for sorting through information. Suppose, for example, that you are interested in learning about some controversial topic—say abortion. You want to get a solid sense of the relevant issues so you can think about it for yourself. To this end there are all kinds of sources available, but you cannot read them all. So how are you going to decide what to read? To simplify, suppose you have narrowed the field to three books. You find out that one of the books is written by the director of a prominent Pro-Life organization, one of the books is written by a prominent member of a Pro-Choice organization, and one is written by a professional bioethicist. Presumably you will choose the book written by the bioethicist, and presumably you will do so on the basis of an ad hominem—there is some reason to think that the overall credibility of the two other books might be compromised (they may not offer a fair presentation of the issues, for example). To be clear: this is not to say that these authors cannot offer a balanced presentation of the issues (we are not appealing to a Denier after all), but only that we have some reason to be suspicious that this is the case. In this case we can justifiably use ad hominems to decide among many possible sources.

Nevertheless, we have to be careful with negative ad hominems. We do not want to unfairly or inaccurately challenge a person’s credibility. This means that we have be sure that the feature in question genuinely gives us good reason to suspect the other person’s honesty or their ability to have an accurate belief on the issue in question. Often simply taking the time to ask this question will allow us to quickly distinguish between logically strong and logically weak ad hominems. That is, once you’ve identified the feature in question ask:

Two Questions to Ask of Negative Ad Hominems: Does this feature…

- Give us reason to think the source is not being honest or sincere in this case?

- Give us reason to think the source is not in a good position to know in this case?

Exercises

Exercise Set 17A:

Directions: For each of the following (i) decide if it is an ad hominem argument or not. If it is a Denier say so. (ii) Using the questions above, briefly comment on the arguments’ logical strength. Be ready to share your answers.

#1:

Health Inspector to Restaurant Owner: Sorry, but I just can’t take your word for it that everything is up to code. In recent years you have claimed to be up to code, but have actually had numerous health code violations.

#2:

Nixon is surely our worst president; after all, no other president has had to resign the office.

#3:

A: According to Senator X, without a boost to defense funding, the U. S. will be at increased risk for a terrorist attack.

B: That has got to be false; Senator X has been a staunch supporter of the defense industry, nobody in the Senate receives more campaign contributions from this industry than X.

#4:

A: The Company’s accountant claims that she is not aware of any accounting irregularities.

B: Whatever, don’t you know that she owns thousands of shares of the company’s stock!

#5:

A: C thinks my relationship with D is not healthy and that we should go out on more dates instead of hanging around the dorm all the time.

B: I wouldn’t exactly take relationship advice from C. She’s never had a long-term relationship.

Exercise Set 17B:

Directions: Assume that all the following are ad hominems. For each case, evaluate the argument for logical strength using the questions above. Explain your answer.

#1:

A: I am totally on board with limiting the capacity of gun magazines. I think that the danger to society of large-capacity magazines outweighs individual’s preferences for them.

B: Whatever, you’ve never even held a gun, much less fired one!

#2:

You can’t take what he says seriously! I mean the guy’s name is ‘Cletus’!

#3:

A: The football team is underfunded. We have by far the lowest operating budget of any team in our conference. We can’t even afford to have our jerseys washed after every game!

B: It is no surprise you’d say that since you’re on the team.

#4:

You can’t take the candidate’s economic policy seriously, I mean the guy has an elevator—for his cars—and gets a $70,000 tax break—on his horses!

#5:

Kid to mom: “How can you stand there and tell me I shouldn’t smoke pot? I know that you did when you were in college!”

#6:

A: The American prison system needs to be reformed. Per capita the U.S. imprisons more of its citizens than any other country in the world.

B: This, coming from a convict. Yeah, right.

Exercise Set 17C:

#1:

This chapter is all about distinguishing logically strong ad hominems from logically weak ones. But why does this matter? That is, why should we care whether our ad hominems are good or not?

#2:

In this chapter we have focused primarily on interpersonal ad hominems. But as we’ve seen, we use ad hominem-style reasoning to sort out trustworthy and untrustworthy sources more broadly. Are there any sources of information you tend to dismiss? On what grounds? Explain.

#3:

What is a conflict of interest? Give an example. How are conflicts of interest related to ad hominem arguments?

- Use of the term 'denier' follows Sinnott-Armstrong, Walter and Fogelin, Robert. (2010). Understanding Arguments 8th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 355-56. ↵