Trump’s Rhetoric: Republican Candidates’ Decision Whether to Adopt It or Ditch It

Siobhan McKenna

Just as the digital age surfaced and transformed over the last two decades, so has political campaigning and the ways in which candidates interact with the public and portray themselves on new social media platforms. After the rise of candidate websites in 1996, e-mail in 1998, online fund-raising in 2000 and blogs in 2004, Twitter has become a legitimate communication channel in the political arena as a result of the 2008 campaign (Tumasjan, 178, 2010). Since Twitter surfaced in 2006, it has been a valuable tool for politicians to communicate with their followers (Evans, Cordova, Sipole, 2014). Today, Twitter has over 310 million monthly active users, making it an essential role of political campaigning in the United States.

Today, in the highly polarized, partisan climate of the United States in which “post-truth rhetoric” is being iterated by our nation’s leader, Twitter becomes an even more crucial arena for politicians to label and portray themselves, especially in relation to President Donald Trump. In the 2018 midterm election, like any other political race, candidates on both sides of the aisle had to consciously decide how to position themselves in relation to the current president in power. Previous literature has examined how Republican candidates running in 2016 responded to the challenge of aligning or disaffiliating themselves with Trump during his candidacy and the explanations for their responses (Liu, Jacobson, 2017). But, there is little research that looks at the Republican candidates running in 2018 and their decision to affiliate or distance themselves from Donald Trump. This study looks specifically at the Republican House incumbent candidates’ who ran for office in 2018 midterm election and their interactions with Donald Trump on Twitter. The number of interactions these candidates have with Trump the month leading up to the 2018 midterm elections is compared to their total interaction with Trump over time, including before and after their election. By tracking candidates’ retweets of Trump, mentions of the President and also whether they incorporated Trump's prominent hashtags, such as, #MAGA and #BuildtheWall, this study examines whether Republican incumbents running in 2018 aligned or disaffiliated themselves with Trump leading up to their election.

Republican candidates in particular have to be weary of their affiliation with Trump for numerous reasons. During the month leading up to the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump was depicted in an Access Hollywood tape boasting about the sexual assaults he committed on women, which were followed by multiple accusations of sexual harassment from victims (Blau, 2016; Liu, Jacobson, 2017). Outside of the moral dilemma of supporting Trump, candidates had to decide how they were going to face Trump's unethical use of rhetoric as well. According to a five day analysis POLITCO did in 2016, Trump averaged one falsehood every three minutes and fifteen seconds over nearly five hours of support (Politico, 2016). Since 2016, Trump has continued to showcase unethical behavior and spew inaccurate claims on social media sites, like Twitter. The analysis in this study indicates the ways in which Republican candidates running in 2018 who have previously supported Trump and supported him after their race, position themselves to Trump during the month leading up to theirs.

Just as there were shifts in party control of the House, there was also a shift in the ways that Republican candidates interacted with Donald Trump on Twitter compared to the ways they reacted with him during the 2016 presidential election. Some Republican incumbents who previously showcased their support for Trump during his election and presidency consciously chose to distance themselves from Trump the month leading up to their election. Others, who ran in “safe” Republican districts decided to showcase their support by praising Trump and tweeting at him more often. This study takes a closer look at examining how Republican candidates shifted their rhetoric from 2016, when Trump was running for President to 2018, when they were running for office.

Scope for Understanding Trump's Post-Truth Rhetoric

During November 2016, the month in which Donald Trump was elected President of the United States, Oxford Dictionaries named “post-truth” the word of the year due to its “spike in frequency” (McComiskey 2017, 5). This word has previously been defined as, “relating to or denoting circumstance in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief” (McComiskey 2017, 5). In Bruce McComiskey’s essay, Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition, he points out, “all rhetorics (until very recently, that is) have existed on an epistemological continuum that includes certain facts, foundational realities, and universal truths, even when these rhetorics do not themselves participate in those facts, realities and truths” (McComiskey 2017, 7). He distinguishes post-truth rhetoric from lies, fallacies and doublespeak, which all can be understood and exist on an epistemological continuum because they “can be compared unfavorably to reasoned opinions and universal truths” (McComiskey 2017, 8). Now that we are in a post-truth world, without truth or lies, language is purely strategic and has no reference to anything other than itself. McComiskey among other scholars have concluded that the event Donald Trump's election has led to the flowering of the post-truth landscape (Marcus 2016, A17, McComiskey 2017, 9).

This theory, along with Politico's analysis which indicates Trump's high rate of speaking falsehoods, indicate that Trump is often lying to the public in order for personal gain. This research will use these claims as a framework for understanding aspects of the 2018 midterm election and Republican's alliance or disaffiliation with Trump. Even though it is clear that a lot of the rhetoric Trump employs can be distinguished as "post-truth" politicians and Republicans still continue to perpetuate it and support him. The study looks at the various ways Republican candidates choose to align with or disaffiliate themselves from Trump and his harmful rhetoric.

Historical Context: Republican Candidates Positioning to Same Party President in Power

In order to understand how Donald Trump’s rhetoric differs from previous Republican presidents, a historical timeline of Republican presidents and their values throughout the course of American history is needed. E. J. Dionne’s book, Why the Right Went Wrong: Conservatism—From Goldwater to the Tea Party and Beyond historically tracks Republican presidents’ models of conservatism over the course of American history. Dionne’s approach distinguishes “traditional Republican president rhetoric” from Trump’s radical conservative rhetoric. It highlights the ideological shifts the party as a whole has made over time (Dionne, 2016). The evolution of the Republican party distinguishes Trump’s “radical conservatism” and rhetorical strategies from previous Republican candidates who ran and were elected president. While there is little research on the historical trend of Republican candidates who are running for office in off year elections choice to affiliate or disaffiliate themselves with the President in their political party, this study plans to uncover the strategical moves Republican candidates made in the 2018 election in showcasing their support or disapproval of the current president, Donald Trump.

Political theories such as the “coattail effect” have often been used to explain the results of midterm elections in American history. This theory suggests that candidates of the same political affiliation as the president are likely to receive a surge in their vote share as a function of the popularity of the president and the propensity of voters to cast a straight-party. Thus, congressmen that are voted in are benefiting off of the president’s coattails (Louise, 2018). One example of a first major coattail was President Reagan’s victory in the 1980 election that was accompanied by the change of twelve seats in the U.S. Senate from Democratic to Republican hands, producing a Republican majority in the Senate for the first time since 1954 (Taegan Goddard's Political Dictionary, 2009).

On the other hand, there have been studies that suggest the coattail effect is not always accurate. A study dating back to 1985 indicates the presidential coattails were “so weak that incumbent congressmen have become quite effectively insulated from the electoral effects… of adverse presidential landslides” (Burnham 1975; Rivers, Rose 1985, 186). Rivers and Rose claim, “congressmen, either of his own party or the opposition, do not owe their election to [the President], nor, if past experience is any guide, can he do much to remove them… A congressman’s best chance to ensure his reelection is through constituency service and credit claiming, and it will probably not make much difference to the votes how faithfully he has supported the president’s program” (Rivers, Rose 1985, 187).

In regards to the 2018 election, Rivers and Rose appear to have right in regards to President Trump's coattails. Donald Trump had among the shortest coattails of any presidential winner going back to Dwight Eisenhower (Cook, 2018). “Some might argue that Trump’s brash, anti-establishment campaign struck a chord with many votes and helped set the tone for Republican victories in 2016. But when it comes to the quantitative side of presidential coattails, the vast majority of Republican House members owe Trump virtually nothing” (Cook, 2018). With these midterm election coattail results, it is clear Trump's coattails align with the findings of Rivers and Rose. Thus, the Republican candidates who expected Trump's coattails to be stronger and chose to support Trump may have overestimated the coattail effect and relied on it too heavily.

Republican Candidates' Position on Donald Trump Leading Up to 2016 Election

A study done by Huchen Liu and Gary Jacobson in 2017 indicated the ways in which Republican Candidates positioned themselves in relation to Trump during the 2016 election. The study looks at the Republican candidates that were also running for President on the Republican ticket with Trump leading up to the primaries. The study takes into account Senate and House Republican candidates’ stance on Trump and the ways it shifted, especially after the Access Hollywood tape was released in October, 2016. The study also takes into account previous Republican candidates that ran for president prior to 2016. Incumbents, non-incumbents and whether districts were primarily Republican or Democratic were also accounted for. They claim, “in short, any endorsement of Trump, let alone a close association with him, appeared to carry serious electoral risks. On the other hand, deserting him was also risky. If Trump appalled Republican leaders and conservative intellectuals, he enjoyed widespread support among ordinary Republicans as well as some conservative talk radio and Fox News personalities eager to join a right-wing populist crusade” (Liu, Jacobson 2017, 49). Republican candidates were aware they had to walk a thin line in their support or disapproval of Trump. Endorsing him too heavily may impact their success especially in areas that were more moderate. But not endorsing him at all could cost them votes with the "ordinary Republicans" who supported him.

This study indicates that every living former Republican presidential candidate—both Bushes, Bob Doyle, John McCain and Mitt Romney--opposed Trump. More than 20 conservative luminaries denounced Trump in the National Review including, Glenn Beck, L. Brent Bozell III, Mona Charen, Erik Erikson to name a few (Liu, Jacobson 2017, 50). Prior to the October 6 surfacing of the Access Hollywood videotape of Trump bragging about his sleazy sexual exploits, 27 of the 33 Republican Senate candidates had expressed some level of support for Trump, albeit with widely varied enthusiasm and with many expressing reservations about his rhetoric, behavior, and qualifications” (Liu, Jacobson 2017, 57). After the Access Hollywood video hit the news, virtually all Republican Senate candidates condemned Trump’s behavior, and many of them wavered or fell silent for a few days. However, only eight withdrew their endorsements. The common theme of those who eventually reconfirmed their support for Trump, was sheer partisanship: he was the Republican nominee and the alternative, Clinton, would deliver an unthinkable third Obama term (Liu, Jacobson 2017, 57). The study shows the ways in which Republican Senate candidates acted in response to an overtly reprehensible behavior of our nation's leader. It shows that while they are aware of it, some even withdrawing their endorsements, in the end they reconfirmed their support. It proves how difficult Republican candidates feel it is to disassociate themselves with the president . Partisanship seems to be one of the only things tying Republican candidates who withdrew and reaffirmed their support to Trump during this election. The Republican incumbents running into 2018 had to decide whether they wanted to continue their support or take a stance that opposes him, even if that means not endorsing him on Twitter.

Significance of Utilizing Twitter

The increase in usage of social networking sites (SNSs) in recent years has led to a revolution in the way we understand political communication and a significant change in the relationship between the political class and their voters (Lilleker, Jackson, 2010; Towner, Dulio, 2012; Alonso-Muñoz, Marcos-García, Casero-Ripollés, 2016; Kruikemeier, 2014; Lilleker, Tenscher, Štětka, 2014; Galán-García, 2017). Twitter is viewed today as a major digital public relations (PR) tool for politics over the last decade, which provides researchers a text to examine the PR strategies of various political candidates (Lee, Lim, 2016). With over 310 million monthly active users, Twitter has become an essential part of political campaigning in the U.S. which is evident after Barack Obama’s successful social media-driven campaign in the 2008 and 2012 presidential race (Conway, Kenski, Wang, 2013; LaMarre & Suzuki-Lambrecht, 2013; Lee, Lim, 2016, Twitter, 2016). A research study done on candidates Twitter usage leading up to their election indicates that candidates that used Twitter during their campaign received more votes than those who did not, particularly when Twitter was used in an interactive way (Kruikemeier, 2014). These findings indicate that a part of all political candidates’ success today is inherently linked to their social-media presence, especially on Twitter, a platform that benefits both the voter and the candidate. Twitter allows voters to communicate directly with candidates and see how they interact with other candidates. It also allows candidates to create an image of themselves in their own words, photos and “Twitter behavior” (i.e. favoriting, retweeting, replying, etc.) while still informing the public of their policies and stance on current issues.

A prior research study examined how House candidates used Twitter in the 2012 campaign. A content analysis of every tweet from each candidate for the House in the final two months leading up to the 2012 election revealed House candidates’ “Twitter style” (Evans, Cordova, Sipole, 2014). The categories included, attack, attack other, campaigning, mobilization, issues, media and user interaction. An example of an “attack” tweet were tweets that attacked or criticized their opponents and an “attack other” tweet was a tweet that specifically attacked the opposing party or the opposing party’s president. For example, Eric Swalwell, a Democratic candidate from California tweeted, “Surprise! Another candidate event and another absence from Pete Stark. Does he know there’s an election or want the job?” This tweet was categorized as an “attack”. Another democratic candidate from California, Jim Reed tweeted, “I’m all for low taxes. GOP’s anti-tax religion has gotten so fundamentalist they see no other needs or priorities.” This was considered an “attack other” tweet. This study looked directly at the rhetoric that House candidates on both sides of the aisle were iterating on Twitter before their election. Findings indicate that Republican and Democrats were very similar in their approach on Twitter in the 2012 election. Republicans “attacked other” or the opposing party 5.6% of the time, while Democrats “attacked other” 3.5% of the time but overall were similar in most regards. (Evans, Cordova, Sipole, 2014).

While this study and the others noted above look into Trump's rhetoric, Twitter analyses and previous Republican candidates support or disapproval of Trump, there has yet to be a study that tracks the recent Republicans' support or disapproval of Trump on Twitter. This study looks into how Republicans retweet, respond and compose their own Tweets "@" or about Donald Trump. By tracking the number of times the candidates interact him, this study shows whether or not candidates intentionally creating a distance between themselves and Trump for their election period. This study takes into account a lot of variables as to why a Republican candidate may choose to distance themselves from Trump including, district, PVI score, and their likelihood to win their race. The previous studies noted above have provided this study with inclinations of previous Republican's behavior in aligning or disaffiliating themselves with Trump and a historical context of how Twitter was used in previous studies. It intends on advancing these findings by applying them to the 2018 midterm House race and offering a new lens for thinking about Republican's relationships to Donald Trump and his post-truth rhetoric.

Choosing the Candidates and Distinguishing Categories

The 2018 Republican House race was chosen due to its broad range and plethora of districts to choose from. Based on the Cook Political Report’s 2018 House Race Ratings that was published before the 2018 midterm election on November 5, 2018, there were 137 solid House seats in which Republicans were very likely to win. Of those 137, Republicans won every seat. Of the 75 vulnerable Republican seats, there were 41 seats won by Democrats (Cook Political Report, 2019). The study takes into account safe, likely and vulnerable Republican House seats.

Republican incumbent candidates in congressional districts were chosen throughout the country in varying states. I consciously picked candidates from races that were both tight and landslide races. The Cook Political Report’s 2018 House Race Ratings was used to distinguish tight races from landslide races. Tight races are the races in which the Republican and Democratic candidate have an equal or very close chance of winning the election. The landslide races are races in which the Republican or Democratic candidate has a proportionally larger advantage over their opponent based off of the ratings the Cook Political Report made prior to the election. This report gave a PVI score or Present Value Index for each of the district House races in 2018. This rating method was first introduced in 1997. The Cook Partisan Voting Index, CPVI or PVI for short, measures how strongly a United States congressional district or state leans toward the Democratic or Republican Party.

Using the Washington Post's Live midterm results House Races page, I was able to select Republican incumbent candidates that were already placed into categories that labeled them to be strong, likely and vulnerable. After selecting a number of incumbent candidates from each category, I broke them into narrower categories. Safe incumbents stayed as is; all of these candidates won their races. The "likely" incumbents were broken down into a small category of two; those who lost to Democrats. Vulnerable incumbents were broken into two categories; those who lost to Democrats and those that beat Democrats. The strong or safe candidates I chose from all have PVI scores of R+15 or higher and were all from districts in which Donald Trump won during the 2016 presidential election. In the two likely incumbents that lost, one of the districts was won by Trump in 2016 and the other won by Clinton. The vulnerable incumbents in both categories all had PVI scores of R+11 or lower and there was a variety of Trump and Clinton won districts.

Republican incumbents were chosen rather than Republican challengers in order to focus the scope of the study to a select group of Republican candidates who were all up for reelection in 2018. The Republican incumbents were all in office during the 2016 presidential election which is imperative for this study because it takes into consideration the districts in which Hillary Clinton won during the 2016 election as a variable for deciphering why the candidate may or may not affiliate themselves with Trump. The total number of Republican incumbents in the study is 36. There was a range of Republican incumbents integrated in the study. This meant "high-profile" races were not chosen over lower stakes races that did not have much publicity. While it would be more impactful to look at every single Republican candidate running in the House race, due to time restrictions and the in-depth lens this study takes at each candidates’ Tweets, this was not feasible. The study offers a birds-eye view approach for understanding a portion of Republican candidates’ decisions to align or disaffiliate themselves from President Donald Trump.

Collecting the Twitter Data

The advanced search option on Twitter was used to record and analyze the Twitter behavior of Republican candidates the month leading up to the midterm election and the overall behavior each candidate had with Trump over time. October 6, 2018 to November 6, 2018 is the time period that was examined and put in to the advanced search tool. Upon putting in the Republican candidates Twitter handle in the “From these accounts” search option, @realDonaldTrump and @POTUS were typed into the “mentioning these accounts” search option. The number of times the Republican candidate mentions either of these accounts the month leading up to the election was recorded and placed into the tables listed below. I then removed the time restriction and recorded the total number of times the candidate interacted with Trump in their total Twitter history since Trump started his campaign for president. Some of the candidates had more than one Twitter account; their personal account and their political account. If candidates have two accounts, their political account was studied. If candidates only have one verified account, it was used in the study.

There are four tables for the four categories that are laid out above. Each table lists the district the candidate ran in, the PVI score, the percentage the incumbent won or lost by, the number of times they mentioned @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS on Twitter the month leading up to the election and the number of times they used the hashtag #BuildtheWall or #MAGA. These two hashtags were chosen because they are two phrases and hashtags that were very prevalent in Trump’s campaign and in his presidency. Tracking the hashtag use of the candidates gave the study a closer look at the type of Trump rhetoric the candidates engaged or disengaged with. Both of these phrases highlight Trump's typical rhetoric he uses not only on Twitter but in speeches, rallies and formal addresses as well.

The same process was used for tracking the hashtag usage as when I tracked the number of times the candidate mentioned Trump. By typing the hashtags "BuildtheWall and #MAGA into the "these hashtags" section of the advanced search and keeping the Republican candidate's Twitter handle in the "From these accounts" option, I was able to see the number of times the candidate used these hashtags. I recorded the number of times the candidate used either of these hashtags, if there was no usage and I place "0" in the data sheet. I recorded whether or not the district the candidate was running in was won by Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election. This was used as a variable to understand why Republican candidates who previously supported Trump on Twitter may have decided not to support him on Twitter the month leading up to their own election.

In-depth Discussion of the Republican Candidates' Interactions with Trump

Not unlike the results of 2016 presidential election, the results of the 2018 midterm election left many politicians and American voters surprised. The voter turnout for this midterm election was 50.3%, the highest voter turnout there has been since 1914 (Washington Post, 2019). The 2018 elections for the House of Representatives was monumental for the Democratic party in multiple ways. The House race, which is composed of 435 seats, was won back by the Democratic party. Prior to the 2018 midterm election, the House was controlled by the Republican party since 2011. In order for the party to win majority, they had to secure 218 seats. Democrats gained 40 seats which secured 235 House seats giving them party control of the House. The Republican party still holds 197 seats and there are also three vacant seats (Washington Post, 2019).

The following data charts and graphs exemplify the ways in which various Republican House candidates interacted with Trump the month leading up to their election in comparison to their entire Twitter history. Republicans who lost and won are located in categories that are listed above. Their interactions are broken down and looked at in detail to decipher how the candidates decided to position themselves in relation to President Trump. The study provides an in depth look at some of the candidates' Twitter pages who stood out in the data as candidates who exemplify supporting and opposing positions on Trump. It offers an analysis as to why they may or may not have decided to distance themselves from him by unpacking their rhetoric in a qualitative natural.

Table 1. Safe Republicans' Use of Twitter

| Safe Republican Candidates | District | PVI score | Percentage won by | Number of times they mentioned @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS on Twitter the month leading up to Election Day | Number of times they used the hashtag #BuildtheWall | Number of times they used the hashtag #MAGA | Total Number of times they interacted with Trump on Twitter | Hillary Clinton won district in 2016 presidential election |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradley Byrne | AL-1 | R+15 | 63.2% to 36.8% | 6 | 6 | 1 | 55 | No |

| Martha Roby | AL-2 | R+16 | 61.4% to 38.4% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | No |

| Robert Aderholt | Al-4 | R+30 | 79.8% to 20.1% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | No |

| Vicky Hartzler | MO-4 | R+17 | 64.8% to 32.7% | 7 | 0 | 0 | 18 | No |

| Phil Roe | TN-01 | R+28 | 77.1% to 21.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | No |

| Daniel Webster | FL-11 | R+15 | 65.2% to 34.8% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | No |

| Bill Johnson | OH-6 | R+16 | 69.3% to 30.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | No |

| Michael Burgess | TX-26 | R+18 | 59.4% to 39.0% | 11 | 0 | 0 | 72 | No |

| Jeff Duncun | SC-3 | R+19 | 67.8% to 31.0% | 3 | 0 | 5 | 57 | No |

| Glenn Thompson | PA-15 | R+20 | 67.8% to 32.2% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | No |

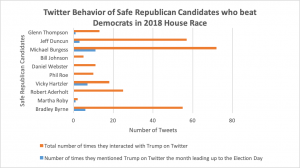

Figure 1. Safe Republicans' Use of Twitter

The first Republican incumbent races that were examined were the "safe" Republican races in which Republican candidates received PVI scores of R+15 or higher. Based on Table 1 and Figure 1, all of these candidates won their races against their Democratic challengers and all of these districts were won by Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Out of the ten Republicans included in this category, all ten of them interacted with Trump at some point over the history of Trump's candidacy and presidency. But, only six of them interacted with him the month leading up to the election. The four candidates that did not interact with Trump the month leading up to the election all interacted with him a minimum of five times and a maximum of twenty five times over the course of their Twitter history. Only three out of ten mentioned him more than five times in the one-month period. On average, safe Republican candidates interacted with Trump 26.8 times in total and 2.9 times the month leading up to the election, the highest in comparison to the other categories. The median number of times they interacted with Trump in total is 15.5 and the median number for the month leading up to the election is 1.

Taking a closer look at candidates' content of tweets and number of interactions is important in deciding who deliberately chose to distance themselves from him the month leading up. The candidates that interacted with Trump the most were Bradley Byrne, Michael Burgess, and Jeff Duncun. All three of these candidates also interacted with him at least 3 times, the month leading up to the election. It appears that these candidates outwardly showed their support for Trump over time and during their candidacy on Twitter.

Michael Burgess of Texas’ 26th district mentioned Trump 11 times in the month leading up--the most out of all the safe Republican incumbents. It is evident that Bradley Byrne of Alabama’s 1st district outwardly supported and reiterated Trump's rhetoric by using the hashtags listed. He was the only candidate to use the hashtag #BuildtheWall which was a total of 6 times. He was also the only candidate that mentioned Trump and used both of the hashtags. His PVI rating was R+15, the lowest it could be to be included in the “safe” category. Jeff Duncun, tweeted at Trump 3 times the month leading up and was the only other Republican candidate to use the hashtag #MAGA during the month leading up to the election. Statistically, these three candidates showed their support for Trump throughout their campaign and did not shy away from reiterating his rhetoric and mentioning him in their tweets.

Republican candidate, Robert Aderholt, who received the highest PVI rating of R+30 did not mention Donald Trump nor use either of the hashtags in his tweets during the month time period. But, in the total course of his Twitter account he interacted with Trump 25 times, which is close to the average number of times these candidates interacted with him. The other three candidates who did not mention Trump at all the month leading up to the election, all interacted with him between five and eighteen times in total. Compared to the averages that are depicted in Figure 2, Aderholt appears to be one of the candidates who chose to distance himself from Trump during this month. By not interacting with him at all, but showing his support outside of this month long time frame, Aderholt did not reiterate Trumps rhetoric nor mention him in any tweets. Considering he is the candidate with the highest PVI score of R+30, he may have felt like he did not need to outwardly support Trump since he felt he could achieve his election on his own. According to Table 1 above, he won his race by a 60% margin, the highest out of all the safe Republicans. With this in mind, it's apparent that candidates who are certain they will win their race do not feel the need to support or disaffiliate from Trump because they feel they are in control of their election.

Similarly, David Webster and Bill Johnson are two candidates that did have any tweets that mentioned Trump or the hashtags the month leading up to the election. Looking closer at their accounts outside of this date range indicate that both of them freely mentioned @realDonaldTrump. Bill Johnson praises the President's accounts in tweets that begin with, “Thank you @POTUS…” and “I applaud @realDonaldTrump…” during the months that are before and after the month leading up to the election. This outward support in comparison to the silence they both take during the month also indicates they are distancing themselves. From this data set, it's unclear the reason they are doing so, but it is apparent they are.

Since none of these candidates were running in districts that Clinton won during the 2016 presidential election, the following graph looks to analyze the district and candidate further by showing the interactions the month leading up in order from lowest to highest PVI score.

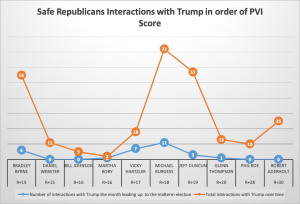

Figure 2: Safe Republicans' Interactions with Trump

Figure 2 indicates that there was a lot of variation in the way safe Republican candidates interacted with Trump the month leading up to the election and their behavior was not dependent on PVI score. This non-linear curve indicates that there is no direct correlation in the PVI and the way these candidates chose to interact with Trump. The third highest number of total tweets (55) came from Bradley Byrne, who had the lowest PVI score in this set of R+15. The three next lowest PVI scores all interacted with him at a much lower number. The two candidates with the highest PVI scores of R+28 and R+30 both chose not to interact with Trump at all the month leading up to the election but interacted with him before. The number of tweets spiked again in the middle with candidate Michael Burgess who tweeted about him 72 times total and 11 times the month leading up, which was the most out of all safe Republicans. Thus, PVI score did not determine how candidates chose to affiliate or disaffiliate themselves from Trump the month leading up to election day.

Table 2. Likely Republican Candidates Twitter Behavior

| Likely GOP Incumbents that Lost to Dems | District | PVI Score | Percentage lost by | Number of times they mentioned @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS on Twitter the month leading up to Election day | Number of times they used the hashtag #BuildtheWall the month leading up to Election day | Number of times they used the hashtag #MAGA the month leading up to Election day | Total Number of times they interacted with Trump on Twitter | Clinton won district in 2016 presidential election |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| David Valadao | CA-21 | D+5 | 50.4% to 49.6% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No |

| Steve Russell | OK-5 | R+10 | 50.7% to 49.3% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | Yes |

This category was unique in comparison to the other three categories since it only includes two candidates because there were only two likely Republican candidates that lost their elections. The table shows Republican incumbents David Valadao who ran in California’s 21st district and Steve Russell of Oklahoma's fifth district. There is no graph because its is fairly easy to interpret the data in Table 2. Both candidates did not interact with Trump nor did they mention his hashtags the month leading up to the election. Steve Russell mentions Trump 6 times in total outside of this month, but upon looking through these few tweets, it's apparent he did support him outwardly with praise as many of the other candidates did, who tweeted at him more frequently. Since this category is small, the analysis looks closely at the political tweets of the candidates the month leading up to the election to see whether their lack of Twitter interactions was due to their lack of support.

David Valadao lost the House race to freshman, TJ Cox by less than .5% of a percentage point. While he was labeled as a "likely" candidate according to the Washington Post, he ran in a district with a PVI score of D+5, which seemed to slightly favor the Democratic candidate. Not only did he not mention @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS on Twitter the month leading up to the election, he also took a political stance on the attacks the Democratic party faced in late October. He retaliated against the attackers who threatened Barack Obama, Hilary Clinton and CNN by sending “suspicious packages” to their homes and offices. On October 24th, 2018 Valadao tweeted, “The attacks and threats against President Obama, Secretary Clinton, news outlets, and others are unacceptable. Such despicable actions have no place in our democracy and will not be tolerated.” Which was a response to NPR’s tweet that stated, “The total of four [suspicious packages] refers to -1 addressed to Hillary Clinton - 1 to former President Barack Obama – 1 to the building that houses CNN’s office in New York City – 1 to Wasserman Schultz, former chairwoman of the DNC.”

While this research does not look into tracking the number of times Republican candidates interact or tweet about members from across the aisle, it is important to note these findings in relation to the study's scope. Valadao, who took this stance a few weeks before his election and also did not interact with or support President Trump at all, lost his election. While it is unable to be proven from this table, it seems that Valadao’s lack of support for Trump paired with the defensive stance against the threats Democrats faced, could have made him an unfavorable candidate in the eyes of Republican voters. Valadao is a candidate that shows to distance himself from Trump completely on Twitter.

Steve Russell was the other Republican incumbent that did not win a seat in the House. He was favored to win with a PVI score of R+10. He interacted a total of six times with Trump over his Twitter history. The last time that he interacted with Trump on Twitter was on January 7, 2016 just after the inaugural address. In two tweets he is asking @POTUS to defund Planned Parenthood, gut Obamacare and justify easing sanction on Iran’s terror financiers. These tweets are asking the President of something and not praising him like many of the other candidates who had higher number of interactions did. Russell has distanced himself from Trump on Twitter since this time and has not mentioned the President during his campaign at all. His tweets focus primarily on the issues that pertain to the district he is running in.

Table 2 indicates that these likely Republican candidates, who were not as "safe" as the candidates in Table 1, distanced themselves from Trump during this month. Both candidates show that they did not openly support him before or after their election as well. This indicates that the candidates were consistent in their distance from Trump; they did not distancing themselves just for the sake of their own election, but did so throughout Trump's presidency and candidacy in 2016.

In comparison to Table 1, Table 2 indicates the safe Republicans' Twitter behavior aligned more in support of Trump than the "likely" candidates. This is not completely certain, since there were four safe candidates that also did not interact with him during the month leading up, but overall the averages of the safe Republicans showed they interacted with Trump more than the likely candidates.

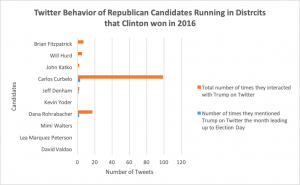

Vulnerable Republican Candidates who Lost to Democrats Twitter Behavior

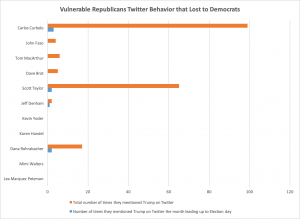

Figure 3 and Table 3 exhibit the Twitter behavior of the Vulnerable Republican incumbents that lost their races to Democrats in the 2018 House race. There were eleven Republicans listed in this category and three of them were women. Out of the eleven candidates, six of the candidates were running in districts that Hillary Clinton won during the 2016 presidential election and five in Trump won districts. There were only four candidates that interacted with him the month leading up to the election, and all did so in small numbers under three. The two candidates that interacted with him the most over in total were Carlos Curbelo and Scott Taylor. The following qualitative analysis looks at whether these two candidates, who appear to be interacting with Trump a lot outside in this month leading up to the election, are distancing themselves from him or not during their election period. The four candidates that never mentioned Trump appear to have distanced themselves from him on Twitter completely.

Table 3 Vulnerable Republicans' Twitter Behavior

| Vulnerable GOP Incumbents that lost to Dem | District | PVI score | Percentage lost by | Number of times they mentioned @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS on Twitter the month leading up to Election day | Number of times they used the hashtag #BuildtheWall | Number of times they used the hashtag #MAGA | Total number of time they interacted with Trump on Twitter | Hillary Clinton won district in 2016 presidential election |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lea Marquez Peterson | AZ-2 | R+1 | 54.7% to 45.2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| Mimi Walters | CA-45 | R+3 | 52.1% to 47.9% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| Dana Rohrabacher | CA-48 | R+4 | 53.6% to 46.4% | 2 | 0 | 2 | 17 | Yes |

| Karen Handel | GA-6 | R+8 | 50.5% to 49.5% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No |

| Kevin Yoder | KA-3 | R+4 | 53.6% to 43.9% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| Scott Taylor | VA-2 | R+3 | 51.1% to 48.8% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 65 | No |

| Dave Brat | VA-7 | R+6 | 50.3% to 48.4% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | No |

| Tom MacArthur | NJ-3 | R+2 | 50.0% to 48.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | No |

| John Faso | NY-19 | R+2 | 51.4% to 46.2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | No |

| Jeff Denham | CA-10 | EVEN | 52.3% to 47.7% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Yes |

| Carlos Curbelo | FL-26 | D+6 | 50.9% to 49.1% | 3 | 0 | 0 | 99 | Yes |

Figure 3 Vulnerable Republican's Twitter Behavior

Figure 3 compared to Figure 1 shows that there is less Twitter engagement with Trump with vulnerable Republican candidates than safe candidates. But, there is one candidate in this category that interacted with Trump the most out of all the candidates in the study. Republican incumbent Carlos Curbelo interacted with Trump 99 times in total. From the scope of this study, it's assumed that this Republican candidate's number of interactions would indicate he supported Trump. Upon analyzing the language in his tweets, I've found that out of the 36 Republican candidates that were sampled, he was one of the only candidates that outwardly opposed Donald Trump on Twitter in a great number of tweets. Majority of his tweets at Donald Trump were open oppositions to his policies and rhetoric. He often argued back with Trump and stated that he is wrong and untruthful. For example, on August 15th 2017, Carlos Tweeted, “@POTUS just doesn’t get it. No moral equivalence between manifestations for and against white supremacy. He’s got to stop.” In response to the Associated Press tweet that states, “BREAKING: Trump says the “alt-left” bears some responsibility for violence in Charlottesville, ‘nobody wants to say that’” (Twitter, 2017).

Just two days before the midterm election Curbelo appeared on MSNBC stating, "The president should not be out there trying to pit one group of Americans against another. He should be trying to unite this country" referring to the President's anti-immigrant midterm strategies (Twitter, 2018). While Curbelo makes this public announcement, Table 3 shows that he only interacts with Trump three times the month leading up. Compared to the surplus number of times he tweeted about or at him outside of this month. It seems that Curbelo is distancing himself more during this month attempting to focus on his districts issues, rather than the Trump administration.

Another interesting aspect about Curbelo is his stance on stereotypically Democratic issues. The month leading up to the midterm election, Curbelo is featured on CNN talking about climate change, "Human beings are affecting the environment in an adverse way ... if we do not take care of our environment, it's going to hurt our economy" (Twitter, 2018). Compared to Trump's rhetoric which denotes climate change as a "Chinese myth" these claims outwardly oppose his beliefs and reverse the post-truth rhetoric he previously employed. In a tweet in 2012 Trump tweeted, The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive" (Twitter, 2012). This post-truth rhetoric regarding climate change ran through his presidency in which he stated recently that he doesn't "believe" it. Curbelo is taking Trump's post-truth and denouncing it as such in ways that openly oppose it.

Carlos Curbelo’s response to when he lost the midterm election also touches on the scope of this study. On November 8th, 2018, he tweeted, “So yesterday @realDonaldTrump stated that had I been more aligned with him, I may have won. Let’s check. I lost #FL26 49-51. My colleague @RepDeSantis who is closely aligned with the Pres lost 47-53" (Twitter, 2018). This tweet speaks directly about Republican candidates affiliation and disaffiliation with Trump. Curbelo points out that he views his open disapproval of Trump and his policies as a factor that did not contribute to the results of his election. By showing that DeSantis, another Republican incumbent running in the House race, closely aligned himself with Trump and lost at a larger margin, he insinuates that support of President Trump does not lead to getting elected. Without outrightly saying so, Curbelo shows that Trump's coattails were ineffective in this election; Republican candidates who tried to support him and hopes to win ultimately did not.

Even though Curbelo is an outlier in this study, by tweeting at Trump the most but actually disapproving him and speaking against his policies, it is imperative that he is included in the study. The analysis done on his tweets specifically indicate that Republican candidates can take more than the two stances this study offers on their relation to Trump. This study suggests that the Republican candidates had two choices. Republicans who supported Trump were noted for their increased number in Twitter interactions. Majority of the time, this was true. Those who tweeted at him and responded to him in greater numbers were the ones showcasing their endorsement and support of his rhetoric in their tweets and retweets by praising him. It was assumed that the Republicans who didn't support him, would not tweet at him at all, or if they did it would be a much smaller quantity. This was also true for the most part, the Republicans who didn't tweet at in large numbers or use the hashtags #MAGA or #BuildtheWall were often ones who did not outwardly praise or thank him. Republican candidates who didn't align with his policies and rhetoric were thought to make the conscious decision to distance themselves from him which showed their lack of support. But Carlos Curbelo was a completely different case and showed there was another stance Republicans in their position to Trump. He tweeted at Trump the most out of all the candidates but did so in ways that openly disapproved of him. He actively spoke out against him and his policies, specifically regarding climate change and his anti-immigrant agenda. Thus, in order to fully understand a Republican's relationship and support of President Trump, looking at the language in tweets is the only way of knowing whether he or she supports him or not. Those who distanced themselves from him, by not tweeting at him at all, can be assumed to be candidates who did not support him or at least did not wish the public to think so.

Now, a closer look at Scott Taylor, who was the only other vulnerable Republican candidate that lost to Democrats that had a substantial difference in the number of times he tweeted at Trump in total compared to the month leading up to the election. Below is a graph that looks closer at the Republicans who ran in districts that Trump won in 2016, which includes Scott Taylor.

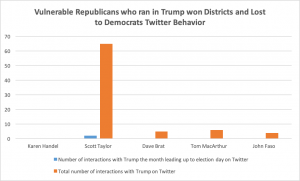

Figure 4 A Vulnerable Republicans Who Lost

Figure 4 shows the majority of the vulnerable Republican candidates who ran in Trump won districts in 2016, did not tweet at him at all the month leading up to the election. Republican incumbent, Scott Taylor was the only one who did. Running in Virginia’s 2nd district he lost to Democrat freshman, Elaine Luria in the 2018 House race. He only mentions @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS twice leading up to the election but he is one of few vulnerable GOP candidates that mention Trump in high volume outside of the month long election period.

Considering Taylor has tweeted at Trump in large numbers before and after the election, analyzing the few tweets the month leading up in comparison to the large sum, indicate that Taylor could be distancing himself from Trump and his rhetoric during this time. Of the two tweets during this month, the only one that directly speaks about Trump is on October 15, 2018. In response to NBC News tweets that corrects the name of a general Trump referred to in a rally. Taylor tweets, "That is quite an error. Why does this sort of thing keep happening to @realDonaldTrump from news organizations who are supposed to be the most professional and the most trusted?" (Twitter, 2018). Prior to the election period, Taylor openly praised Trump in a number of tweets. One of them being, "Thankful for @realDonaldTrump for keeping his promise! #Israel. Proud to be part of this historic day in this holy city." on May 14, 2018 (Twitter, 2018). Outside of tweeting praises, Taylor also shows his support by posting photos with Trump back in January of 2017. He tweeted "Why not get a couple shots with the #POTUS @realDonaldTrump as well?" with two photos of him and Donald Trump smiling (Twitter, 2017).

These outward praises that occur outside of the month of the election period indicate that Scott Taylor does support Trump to an extent. His lack of interaction with him the month leading up to the election may or may not indicate that he distanced himself from Trump. Compared to the other vulnerable Republicans running in Trump won districts, he was the only one who mentioned him at all but did so in ways that didn't openly support him, rather he questioned why a news source had misquoted him.

Figure 4 shows Dave Brat as another vulnerable Republican who tweeted at Trump before and after the election period but not during the month leading up. This Republican incumbent ran in Virginia’s 7th district and lost to freshman Democrat, Abigail Spanberger. He stood out in relation to the other Republican candidates in terms of his Twitter behavior. While he did not mention @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS in his tweets the month leading up to the election, he mentioned open praises for Vice President, Mike Pence (@mike_pence or @VP) in 4 separate tweets. He also used the hashtag #MAGA 5 times leading up to the 2016 Presidential election and included Mike Pence in 4 out of 5 of those tweets.

While he separates himself from the #MAGA hashtag during his campaign, he used it often when Trump and Pence were on the ticket. It is interesting that he adopts Trump’s rhetoric when he is supporting him but strays away from it when he is running for office himself. This may have to do with the fact that he acknowledges he is a vulnerable GOP candidate and excessive support of Trump and his rhetoric could negatively effect his reelection. Since he did not mention Trump or Pence once the month leading up, it seems he has distanced himself from the administration. Table 3 indicates his PVI score is R+6, this vulnerability places him as a candidate in a district that may not support Trump or Pence to the same degree as a safe district. This could be a factor in his choice of distancing himself from Trump.

Table 4. Vulnerable Republican Incumbents Who Beat Democrats

| Vulnerable GOP Incumbents that beat Democrats | District | PVI score | Percentage won by | Number of times they mentioned @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS on Twitter the month leading up to Election day | Number of times they used the hashtag #BuildtheWall the month leading up to Election day | Number of times they used the hashtag #MAGA the month leading up to election day | Total number of time they interacted with Trump on Twitter | Hillary Clinton won district in 2016 presidential election |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steve King | IA-4 | R+11 | 50.3% to 47.0% | 3 | 0 | 0 | 62 | No |

| Mike Bost | IL-12 | R+5 | 51.6% to 45.4% | 5 | 0 | 0 | 59 | No |

| George Holding | NC-2 | R+7 | 51.3% to 45.8% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | No |

| Jaime Herrera Beutler | WA-3 | R+4 | 52.7% to 47.3% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No |

| Vern Buchanan | FL-16 | R+7 | 54.6% to 45.4% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | No |

| Rob Woodall | GA-7 | R+9 | 50.1% to 49.9% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 36 | No |

| Chris Collins | NY-27 | R+11 | 49.1% to 48.8% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88 | No |

| Andy Barr | KY-6 | R+9 | 51.0% to 47.8% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | No |

| Fred Upton | MI-6 | R+4 | 50.2% to 45.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No |

| Duncan Hunter | CA-50 | R+11 | 51.7% to 48.3% | 6 | 2 | 0 | 61 | No |

| John Katko | NY-24 | D+3 | 52.6% to 47.4% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Yes |

| Will Hurd | TX-23 | R+1 | 49.2% to 48.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | Yes |

| Brian Fitzpatrick | PA-1 | R+1 | 51.3% to 48.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | Yes |

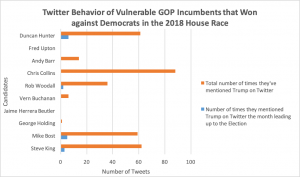

Figure 5. Vulnerable Republican Incumbent's Who Who Beat Democrats

Figure 5 shows a large difference in the number of interactions between these vulnerable candidates that won. Of the ten candidates, two never interacted with Trump at all and six did not interact with him the month leading up to the election. The total number of tweets each Republican tweeted to Trump was on the higher end in comparison to the vulnerable candidates that lost.

Steve King, a Republican incumbent from Iowa’s 4th district was a candidate that interacted with him frequently. Table 4 shows that Steve King did not use #MAGA or #BuildtheWall the month leading up to the election. After looking more closely at his tweets, I noticed that he used these phrases but without a hashtag. For instance, on October 9, 2018 he mentioned an article title, “Shock report: US paying more for illegal immigrant births than Trump’s wall” and said, “Build the Wall!” It’s certain that King is reiterating Trump here and using the same phrases that he does but it does not fall into the scope of this study. Thus, there is a limitation in discovering whether or not Republican candidates are using Trump's rhetoric since it only accounts for hashtags and not all words. It is clear that King is interacting and reiterating Trump in other ways.

Republican incumbent Chris Collins who ran and won against democratic freshman Nate McMurray seems to be distancing himself from President Trump. He did not interact with Trump the month leading up to the election but prior and after the election period, he tweeted 88 times, the highest amount in this data set. Looking at the tweets outside of this month, he included the hashtag #MAGA 26 times in total but table 4 shows he did not use it at all the month leading up to the election. While this study did not track the number of times the candidates used these hashtags outside the month, this finding seems imperative for discussing the study's limitations but also Collins direct disaffiliation from Trump during this time period. Considering he is a “vulnerable” candidate and won his election with less than 1% point, his distance from the President appears to be deliberate. After November 6, 2018 Chris Collins does not shy away from mentioning the president nor does he shy away from adopting his slogan, “Make America Great Again.” Table 4 shows there are four other candidates that have interacted with Trump outside of the month, either before or after the election period.

On the other hand Figure 4 shows that Representative Duncan Hunter was one of the only vulnerable GOP’s that won reelection that tweeted about or at Trump the month leading up. His tweets indicate he was one of the only candidates that openly support Trump on Twitter the month leading up to the election. He tweeted about or at @realDonaldTrump or @POTUS 6 times within the month and was the only candidate to use the #BuildtheWall hashtag within the month as well. He did not shy away from his support of the president unlike the other vulnerable candidates who did, and won.

Within these vulnerable categories there is still a broad range of supporting and distancing oneself from Donald Trump. The candidates who are similar, in terms of PVI scores and vulnerability all differ in terms of distancing and affiliating themselves with Trump. It's clear that the candidates do so on an individual basis that is not determined solely on their likelihood to win their district. Candidates may be distancing themselves for moral reasons. Carlos Curbelo for instance is a candidate that openly opposes Trump. He is aware that as a Republican candidate this could hurt his chances of becoming reelected yet he does so anyone. While winning his election is important, it's also clear that he distances himself from Trump because he is not feeding into his untruthful rhetoric.

Conclusions on Twitter Interactions

Figure 6. Republican Twitter Behavior in Clinton Districts

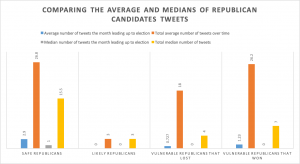

Table 5. Republican Tweets

| Safe Republicans | Likely Republicans | Vulnerable Republicans that Lost | Vulnerable Republicans that Won | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average number of tweets the month leading up to election | 2.9 | 0 | 0.727 | 1.23 |

| Total average number of tweets over time | 26.8 | 0 | 18 | 26.2 |

| Median number of tweets the month leading up to election | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total median number of tweets | 15.5 | 0 | 4 | 7 |

Figure 7. Republican Tweets

The final two Figures, 6 and 7, show in detail the candidates who ran in Clinton won districts in 2016 and a comparison of the averages and medians of each category. Figure 7 shows that Safe Republicans were the most likely to interact with Trump on Twitter the month leading up to the election. On average they interacted with Trump 2.9 times the month leading up to the election, while the other categories didn't come close. The total averages indicate that safe Republicans and vulnerable Republicans who won, tweeted at Trump on average almost the same amount and the most.

The vulnerable Republicans that lost were in the same ball park but significantly less than the safe and vulnerable candidates who won. It's also important to point out that the vulnerable Republicans who lost also include outliers such as Carlos Curbelo, which spiked the numbers in Figure 7. Looking at Figure 5 and 3 next to each other show that there was a larger gap in Twitter interaction than the average graph indicates. It's important to point out that the vulnerable candidates who lost were not any more "vulnerable" than the vulnerable candidates who won; they all had PVI score ranging from D+6 to R+11. It is interesting that the vulnerable candidates who won interacted with Trump at a greater number in total compared to the vulnerable candidates who lost.

Figure 6 provides insight on the candidates running in Clinton won districts. Once excluding Carlos Curbelo's as an outlier, it is clear from this graph that in all these candidates interacted with Trump far less during the month leading up to the election and in total compared to the candidates who ran in Trump won districts in 2016. This appears to be one of the only conclusive factors that shaped Republican candidate's twitter interactions with Trump on Twitter. The highest total number of tweets comes from Dana Rohrabacher with 17 which doesn't even meet the averages of the three safe and vulnerable categories. Out of these nine, only two candidates interacted with him the month leading up to the election and it was less than twice. It appears from figure 6 that majority of the candidates running either distanced themselves from Trump by tweeting at him at small amounts or completely denounced him like Carlos Curbelo. The Republicans running in Clinton won districts were aware that there was not the same overwhelming amount of support for Trump in places like the "safe" districts in which Trump won a much higher margin. These candidates seem to be taking into consideration a distance from Trump could win them votes from Republican voters who did not support Trump back in 2016.

Majority of the Republican candidates interacted with Trump at some point over the course of their Twitter history. But there were also candidates who never interacted with him at all. Eight out of thirty six Republican candidates never interacted with Trump on Twitter. Of those eight, four of them were women. Out of the thirty six Republicans in this study, only six of them were women. While there are a fewer number of women in this study, majority of the Republican incumbents running for office were men, thus the number of women this study sampled from was smaller. It is interesting to point out that of the six women Republicans in this study, four of them did not interact with Trump at all on Twitter. This indicates that the women running for Republican seats statistically distanced themselves from Trump more than the men did.

Overall very few candidates used either of the hashtags, #MAGA or #BuildtheWall leading up to the election. This could be due to the fact that the candidate just didn't use these specific hashtags and could have been reiterating Trump's rhetoric in other ways. The study shows that one candidate used these phrases but did not include them in a hashtag. This still reiterated Trump's rhetoric but didn't appear in the data because it didn't take into considering words outside of hashtags. But, the ones that did use these hashtags, had a higher amount of tweets on average compared to the rest of the Republicans in the study. This indicates that these were candidates that supported Trump and actively reiterated Trump's rhetoric.

While it is clear that the safe Republicans were openly more supportive of Trump the month leading up to the election than the other candidates, it is difficult to differentiate whether or not the likely Republicans supported or distanced themselves due to fact there were only two Republicans in that category. The three other categories all had at least 10 candidates.

The safe Republicans were the only category in which every one of the candidates interacted with Trump at some point over their Twitter career, the three other categories at least one of the candidates did not interact with him at all. This indicates that these safe Republicans appear to be more in support of Trump. Since they are running in "safe" districts it can be assumed that these districts have a more concentrated population of Republican voters. A more conservative candidate, that aligns with Trump, is more likely to succeed in a district such as these than it would in a vulnerable district. The strategies that these safe Republicans used, of affiliating themselves with Trump thus had to do with the fact they were comfortable and aware their district was one who previously voted for Trump in 2016 and still supported him.

But what is most interesting about this data is perhaps within the tweets themselves. The data sets and figures focus on the number of times the candidates interact but aren't able to look at the qualitative side of what each candidate is saying. It became clear that support does not correlate directly with number of tweets the candidate directs at Trump. The candidate Carlos Curbelo showed this to be true in his outward dislike of Trump in a high volume of tweets. This study proves that it is difficult to come to any legitimate conclusion based off of quantitative Twitter data alone. While it provides and interesting look at Republican's decision to interact more or less with Trump during their election period, to find out whether Republican candidates openly support Trump and his policies a look at every candidates' specific rhetoric is needed.

References

Alonso-Muñoz, Laura; Marcos-García, Silvia; Casero-Ripollés, Andreu. 2016. “Political leaders in (inter)action. Twitter as a strategic communication tool in electoral campaigns”. Trípodos, n. 39, pp. 71-90. http://www.tripodos.com/index.php/Facultat_Comunicacio_ Blanquerna/article/view/381/435

Burnham, Walter Dean. 1975. Insulation and responsiveness in congressional elections. Political Science Quarterly, 90 (Fall):411-35.

"Coattail Effect." 2009. Taegan Goddard's Political Dictionary. October 20. Accessed April 03, 2019. https://politicaldictionary.com/words/coattail-effect/.

Cogburn, Derrick L.; Espinoza-Vasquez, Fatima K. 2011. “From networked nominee to networked nation: Examining the impact of web 2.0 and social media on political participation and civic engagement in the 2008 Obama campaign”. Journal of political marketing, v. 10, n. 1-2, pp. 189-213. https://ucdenver.instructure.com/courses/337926/ files/3219879/download?wrap=1 https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2011.540224

Conway, B. A., Kenski, K., & Wang, D. 2013. Twitter use by presidential primary candidates during the 2012 campaign. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 1596–1610.

Cook, Rhodes. "Sabatos Crystal Ball." Larry J Sabatos Crystal Ball RSS. Accessed March 21, 2019. http://www.centerforpolitics.org/crystalball/articles/donald-trumps-short-congressional-coattails/.

Evans, Heather K., Victoria Cordova, and Savannah Sipole. 2014. "Twitter Style: An Analysis of How House Candidates Used Twitter in Their 2012 Campaigns." PS: Political Science & Politics 47, no. 02 (2014): 454-62. doi:10.1017/s1049096514000389.

Galán-García, María. 2017. "The 2016 Republican Primary Campaign on Twitter: Issues and Ideological Positioning for the Profiles of Ben Carson, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Donald Trump." El Profesional De La Información 26, no. 5: 850. doi:10.3145/epi.2017.sep.07.

Gonawela, A’ndre, Joyojeet Pal, Udit Thawani, Elmer van der Vlugt, Wim Out, and Priyank Chandra. 2018. “Speaking Their Mind: Populist Style and Antagonistic Messaging in the

Supported Cooperative Work (Cscw) : The Journal of Collaborative Computing and Work Practices 27 (3-6): 293–326.

Kruikemeier, Sanne. 2014. “How political candidates use Twitter and the impact on votes”. Computers in human behavior, v. 34, pp. 131-139. https://goo.gl/LJcVax https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.025

LaMarre, H. L., & Suzuki-Lambrecht, Y. 2013. Tweeting democracy? Examining Twitter as an online public relations strategy for congressional campaigns. Public Relations Review, 39, 360–368.

Lee, J, and Y.-S Lim. 2016. “Gendered Campaign Tweets: The Cases of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump.” Public Relations Review 42 (5): 849–55.

Lilleker, Darren G.; Jackson Nigel A. 2010. “Towards a more participatory style of election campaigning; The impact of web 2.0 on the UK 2010 general election.” Policy & internet, v. 2, n. 3, pp. 67-96)

Lilleker, Darren G.; Tenscher, Jens; Štětka, Václav. 2015. “Towards hypermedia campaigning? Perceptions of new media’s importance for campaigning by party strategists in comparative perspective.” Information, Communication & Society, v. 18, n. 7, pp. 747-765. https://goo.gl/2NkmQ9 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.993679

Liu, Huchen, and Gary C Jacobson. 2018. “Republican Candidates' Positions on Donald Trump in the 2016 Congressional Elections: Strategies and Consequences.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 48 (1): 49–71.

Louise, Rhonda. "Midterm Elections." In Encyclopedia of U.S. Campaigns, Elections, and Electoral Behavior, by Kenneth F. Warren. Sage Publications, 2008. https://muhlenberg.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/sageuscamp/midterm_elections/0?institutionId=4200

McComiskey, Bruce. 2017. "Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition." Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition, 1-50. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1w76tbg.3.

Oborne, Peter. 2017. How Trump Thinks: His Tweets and the Birth of a New Political

Language. London: Head Of Zeus. https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=48762bf4-cfb2-47d0-83a2-83ffe887f455%40sessionmgr4009&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=1548222&db=nlebk

Rivers, Douglas, and Nancy L. Rose. 1985. "Passing the Presidents Program: Public Opinion and Presidential Influence in Congress." American Journal of Political Science 29, no. 2: 183. doi:10.2307/2111162.

Solop, Frederick I. 2009. “RT @BarackObama We just made history. Twitter and the 2008 presidential election”. En: Hendricks, John-Allen; Denton, Robert E. Communicator-in-chief: A look at how Barack Obama used new media technology to win the White House. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, pp. 37-49. ISBN: 978 0 739141052

Towner, Terri L.; Dulio, David A. 2012. “New media and political marketing in the United States: 2012 and beyond”. Journal of political marketing, v. 11, n. 1-2, pp. 95-119. https://goo.gl/CdLD6m https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2012.642748

Twitter, Inc. 2012-2018.