In the “Year of the Woman” Why are Republican Women Falling Behind?

Audrey Quinn

As increasing numbers of Democrat women are elected to Congress, Republican women’s representation is not similarly increasing and, in fact, in many ways, is decreasing. This project seeks a deeper understanding of the gap between Republican women and Democratic women in elective office. I consider trends in the US Senate through the lens of geography and regional differences. Overall I find that generally there is a consistent lack of women’s representation in the West compared to Eastern region United States. We also find that since 1980, no elected Republican women has served in the Senate in from the Western United States while many Democratic women have. Over the past 40 years there has been a decline in the numbers of women elected from Southern states and an increase in the numbers elected from the Midwest.

What We Already Know

Throughout history there has been a well-known and documented gap between representation of men and women in American Politics (Griffin, Newman, Wolbrecht 2012). However, as the 2018 midterm elections indicate, the gap is closing. However, a new gap has been growing and that is the gap between women’s representation in the Republican party and women’s representation in the Democratic party. In this past midterm election, 350 women filed to run as Democrats for the House while only 118 women filed to run as Republicans. Of women running for the House in 2018, 105 Democratic women won primaries compared to only 25 Republican women (Bacon 2018). Fewer Republican women run for office and fewer Republican women win (Thomson 2015). Geography, and its intersection with party and regional cultures, offers one possible explanation for these trends.

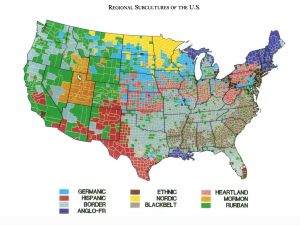

The concept of regional political differences generally has been studied for many years. Much of the recent progress being made in this field has been done by Joel Lieske who expanded upon Elazar’s work, the forefront of research on regional subcultures in America. Lieske’s (1993) research identified ten distinct but homogenous subcultures within the United States. He identified these cultures as Germanic, Ethnic, Heartland, Hispanic, Nordic, Mormon, Border, Blackbelt, Rurban, and Anglo-French; all of these can be seen geographically in Appendix A. Between these subcultures, Lieske found differences in political behavior as well as social issues that effect them uniquely. Lieske updated his 2003 work in 2010 to take into account immigration and cultural disbursement and the geographic movement of subcultures. Those subcultures with the highest voter turnout in 1980 were Mormon with 73.4%, Nordic with 72.2%, and Germanic with 65.6%; subcultures with lowest turnout were Blackbelt with 49.1%, Rurban with 51.9%, and Hispanic with 52.4%. In terms of how they voted in the Presidential election of 1980, Germanic voters had a strong lean to the Republican candidates, Ethnic voters were more split but leaned Republican, Heartland voters had a strong lean to the Republican candidate, Hispanic voters had a slight lean to the Republican candidate, Nordic voters had a strong lean to the Republican candidate, Mormon voters had the strongest preference for the Republican candidate, Border voters had a slight lean to the Republican candidate, Blackbelt voters has a moderate lean to the Democrat candidate, Rurban voters had a strong lean to the Republican candidate, and Anglo-French voters had a slight lean to the Republican candidate (Lieske 1993). What Lieske establishes is that there are regional differences that include subcultures that have an effect on political behavior.

Looking purely at geographic region however, there is still a statistically significant relationship between geographic region in the United States and political opinion (Weakliem and Biggert 1999). Specifically, research indicates that overall the New England area (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont) is the most liberal on average in terms of their political beliefs, the second most liberal is the Pacific region (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington), and the third most liberal is the Middle Atlantic region (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania). Following the Middle Atlantic is the West North Central region ( Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota) as the most liberal. The Mountain region (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming) is the most moderate while the East North Central region (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin) is fourth most conservative. The third most conservative overall is the South Atlantic region (Delaware, Washington D.C., Georgia, Florida, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia), the second most conservative is East South Central (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee), and the most conservative overall in terms of their political opinion is the West South Central region (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas) (Weakliem and Biggert 1990). In this we can see how the political opinions of voters is related to their region in the United States which would reflect their voting patterns.

Historically, it has been found that when women run, their gender tends to actually have a positive effect on their campaigns in terms of media attention and financing (Darcy and Schramm 1977). However there have been studies showing that seeking women’s representation is significantly more of an issue for Republican women than Democratic women. In previous years when Republican women ran against Democratic men they performed worse than when Republican men ran against Democratic men but, when Democratic women ran against Republican men, they performed better than Democratic men (Darcy and Schramm 1977) One proposed cause of this is because Republican women often cross party lines to support women candidates, but it is rare that Democratic women cross party lines to vote for a Republican women (Brians 2005). Brian’s research found that there was a 31.9% chance that in a race between a Republican woman and Democrat man, a Democratic woman would vote for the Republican candidate. However, there is a 45% probability that in a race of a Democrat woman against a Republican man, a Republican women vote for the Democratic candidate. About 30 years ago women in Congress were just as likely to be Republican as Democrat. However the initial big shift occurred in 1992 during the first “Year of the Women” when 54 women were elected to Congress but only 14 of those women were Republican (Center for American Women and Politics 2018). This trend and current political polarization seem to imply that this gap will not be closing any time soon.

When comparing Democratic women and Republican women one of the first obvious signs of the gap is that fewer Republican women run. However, one of the bigger differences is in that while women in general tend to be more liberal than men, Republican women are more liberal than their male counterparts when compared to how much more liberal Democratic women are in relation to their male counterparts (Vega and Firestone 1995). This statistic also carries over into their voting patterns after they are elected into Congress. Research looking into women candidates from the election years 1994-2010 found that not only are there more Democrat women running but there are also more Democrat women running for open seats compared to Republican women (Burrell, Carroll, and Sanbanmatsu 2014). Open seats are statistically significantly easier to win than incumbent seats so a mix of circumstantial, regional, and strategical issues mean races Republican women tend to run in more competitive races.

While some may tend to focus on the number of Republican women in Congress compared to Democratic women, some of the more pressing issues are within the Republican party itself. Although many political scientists have found the political field to be favorable to Republicans recently, Republican women are still finding themselves in a standstill in terms of their growth in Congress (Och and Shames 2018). The same political scientists making these claims also assert that the issue is cyclical and that the low numbers of Republican women in the public eye are creating a negative public image for the Republican party in terms of representation of women as well as women empowerment. One of the biggest obstacles for women to overcome however is the growing conservatism of the Republican party and its fairly recent ties to the Religious Right and Evangelical Christians. As the party has gotten more conservative it has been harder and harder for women who already tend to be more moderate to position themselves as true conservative woman instead of as a moderate Republican (Och and Shames 2018). Not only is the growing conservatism in the Republican party hurting the numbers of Republican women in Congress but as our country gets continuously more politically polarized there comes issues with finding successful moderate candidates, and even if a woman were to position herself as very conservative the general public thought is that women will always be more liberal than men and therefore will not be an asset to the Republican party when going against the Democrats (Thomson 2015).

Another huge hurdle facing Republican women is that the implications of gender stereotypes differ depending on party affiliation. While women face stereotypes regardless of party the stereotypes found to be held about Democrat candidates were positive, while the stereotypes found to be held about Republican women candidates were more detrimental (Sanbanmatsu and Dolan 2008). In this same study not only were Republican women more likely to be seen as too liberal to be a Republican candidate but Republican voters were significantly more likely than Democrat voters to question the emotional capabilities of women and if they would be able to handle the position of a Congresswoman. Region has also played a part in hindering the representation of Republican women in Congress as there has been more growth for the Republican party as an entire entity in the South, however the South has the lowest numbers of proportional women’s representation among state legislature (Center for American Women and Politics 2019). Overall one of the biggest hindrances to Republican women has been the Republican party and voter base itself as they move even more towards the right and start aligning further with conservative values.

As previously discussed, the party gap in women’s representation in Congress can mostly be attributed to the lack of Republican women running. However, while we know that there are fewer Republican women running for Congress, a lot can be found out from addressing the issue at the beginning and looking at the primaries. Research analyzing primary races from 1994 to 2010 finds that even in the primaries more Democratic women are running than Republican and in they are more likely to run in elections where there is an open seat. Burrell, Carroll, and Sanbanmatsu also find that regardless of incumbency or if an election is for an open seat, Democratic women consistently win more than Republican women (Burrell, Carroll, and Sanbanmatsu 2014). A concerning figure however points to the fact that it is not that Republican women do not want to or do not find themselves capable of running for office, it is that there is something else keeping them from candidacy. Republican and Democratic women are equally likely to feel qualified, with 20% of women from both parties assessing themselves as very qualified for office and Democratic women are actually more likely to find themselves to be not at all qualified with 12% assessing themselves that way and only 10% of Republican women self-assessing the same (Fox and Lawless 2011). Along with this, women, regardless of party affiliation, self-assessed significantly lower then men overall in their qualifications for candidacy. One of the explanations given in the research was that because men have always seen other men in these positions they find it more attainable than women, however going off of that thought process one would assume that because there’s significantly less Republican women than Democratic women in Congress the scores would be lower for Republican women but they are not. While it is true that Democratic women are running generally more so than Republican women, a factor in the gap is that Democratic women are winning their primaries in higher proportions than Republican women.

In regard to the 2018 elections specifically, several possible theories have already been proposed to attempt to explain the biggest partisan gap among women we have ever had. One of these being that this partisan gap is reactionary to Trump’s campaign and time in office. With the resurgence of the women’s movement being specifically tied to sexism from the President, a record number of Democrat women ran for office and specifically focused their campaigns as staunchly anti-Trump (Fox and Lawless 2018). Also, this midterm already provided a generally unfavorable field to Republicans as midterms tend to sway against the executive party in order to maintain checks and balances. This year specifically, exit polls also showed the differences in priorities for voters depending on party alignment. Overall, the American voting population overwhelmingly found it important to elect women this election with 8 out of 10 voters saying this but of those two thirds voted Democrat whereas 8 out of 10 of those that saw it as not a serious problem voted Republican (Kurtzleben 2018). This would support the theory that Democratic voters are more purposeful in voting for women than Republican women.

Although the question as to why specifically there is this huge and growing partisan gap among gender can’t be unequivocally asserted, I plan to identify trends throughout the United States and find correlations between regional differences and likelihood of electing Republican women. Through looking at the difference of women’s representation in the Democratic Party and Republican Party through the lens of geography I intend to find underlying themes and possible regional explanations for this phenomenon.

Methods

In order to analyze how geography and region in the United States has affected the disproportionate numbers of partisan women in the US Senate, I have created maps depicting the states in which Republican or Democrat women have served. These maps reflect the breakup of women in the US Senate every six years starting in 1980 and continuing on to present day. With these maps I plan to identify certain regional trends over time and see if there are any regions that are electing more woman than not and if there are some that are electing certain parties of woman more than not. In total I have created eight maps which show the states where women are serving in Senate. For the purpose of this research and in hopes of analyzing this data as a reflection of the American vote, I have excluded woman who have been appointed to their positions in Senate on the map. Including women who were appointed to their position would negate the concept that some people specifically vote against candidates because they are women. I also have defined the five regions of the continental United States as Northeast, Southeast, Southwest, Midwest, and West.

I also intend to look specifically at the 2018 midterm election and use the five senate elections in which Republican woman ran which coincidentally span the five regions of the United States as individual case studies for their respective regions. For these five elections which took place in Nebraska, Washington, Tennessee, New York, and Arizona I analyze exit polls from these elections to identify any trends that either carry across all regions or if they are unique to that election. The difficulty in comparing these elections is that in all but one, the opposing candidate was a Democratic woman and in the other was a Democratic man so it will be difficult to make blanket statements about Republican women running as every election is affected by both running candidates.

Findings

Since 1980, eleven Republican women have been elected into the United States Senate, while twenty-four Democrat women have been elected (CAWP 2019). The following maps reflect the states in which an elected women is serving in the US Senate for that particular year.

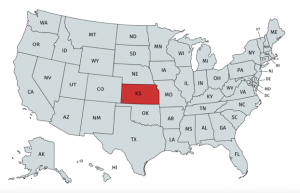

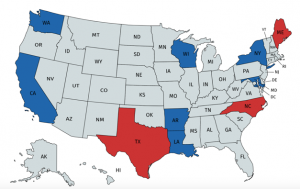

Map 1. States with Elected Women Serving in Senate in 1980

As Map 1 depicts, where we start in 1980, there is only one woman elected to the United States Senate. Nancy Kassebaum made history as the first woman to ever be elected to a full Senate term without her husband previously serving in Congress. She defeated eight other Republicans in the primaries for her first election to Senate and went on to beat out former Democratic Congressman Bill Roy in the general election of 1978. This map sets precedent for the future as at this point there were no Democratic women serving in the Senate and Kassebaum was able to secure a seat in the Midwest which we will later see will not be as common.

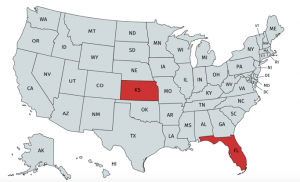

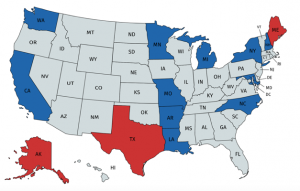

Map 2. States with Elected Women Serving in Senate in 1986

Six years following Nancy Kassebaum’s historical win, she continues to hold her seat in the United States Senate and at this point only one other woman is elected to Senate. Republican Paula Hawkins from Florida who remains the only woman elected to Senate from Florida and is the first women elected into the Senate without having a family member serve in a major public office as Kassebaum’s father was Governor of Kansas. This map shows that the partisan gap among women in Senate was not always so favorable to Democrats as recently as 1986, the only two women elected in Senate at the time were Republican.

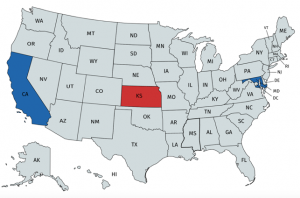

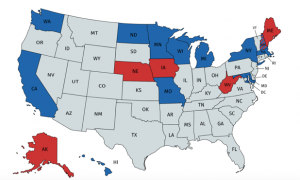

Map 3. States with Elected Women Serving in Senate in 1992

Map 3 depicts the geographical makeup of women in Senate by party immediately prior to the first “Year of the Women” in 1992. In this year, Kassebaum still holds her position as Senator but there have been no other elected additions of Republican women in the Senate. However, we see our first elected Democrat woman in Senate since 1980 in California and Maryland. Barbara Mikulski is begins her tenure in 1987, a seat she held until her retirement in 2017. Dianne Feinstein was actually elected in 1992 during a special election to fill Senator Pete Wilson’s seat which was vacated when he moved to the Governor position. Although a second women in California was elected into the other Senate seat in 1992, her term didn’t begin until 1993 and so her position is not reflected in this map. It is also here when we begin to see women start to gain more momentum in the West however as we will see later this will benefit the Democratic party alone.

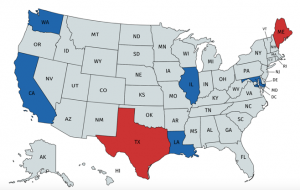

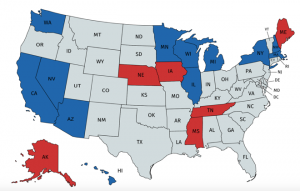

Map 4. States with Elected Women Serving in Senate in 1998

Map 4 includes the women elected during the 1992 “Year of the Women”. As shown, Democratic women picked up a second spot in California, one in Louisiana, one in Washington, and one in Illinois. They also remained in a seat in California and Maryland. At this point there are six Democratic women in Senate and three Republican women after two won Senate seats in Maine and one in Texas. If including Dianne Feinstein’s win in the special election a total of four Democrat women won Senate Seats in the 1992 election and only one Republican did in Texas. The 1992 elections were a landmark time for women in politics and it is where we first start to see the beginnings of the current partisan gap in Congress and in Senate as shown. At this point we also see that the Democrats have women in every region except the Southwest consisting of AZ, NM, TX, and OK.

Map 5. States with Elected Women Serving in Senate in 2004

As we move into the 21st century we see many gains for women in the Democratic party as they pick up a seat in Arkansas, a second seat in Washington, a seat in New York, and a seat in Michigan. Meanwhile, at this point Republican women have only picked up North Carolina. At this point we can see how outweighed the Democratic women are compared to Republican women. As has been fairly consistent, we see a cluster of states in the Midwestern and Western region of the United States without any women elected into the Senate. At this point nearly every state with an elected woman in Senate is on the border with only one, Arkansas, not being on the border but being very close and having borders with two other states with continental borders. Whether or not this is significant it proves to be very interesting especially considering that in the first map the only state with an elected woman in Senate was Kansas.

Map 6. States with Elected Women Serving in Senate in 2010

In 2010 there still is only three states with Republican women in Senate while eleven states have Democratic women, nearly four times as many. After being appointed in 2002, Lisa Murkowski is elected for a full six-year term in Alaska. Because in 2004 Murkowski was still serving the remainder of her appointed term her seat was not reflected in the previous map but as she is elected in 2004, we see her appear here. At this point Republican women are being elected in similar places in the continental United States while Democrats start to gain more traction across the map but there is still a lack of women in the cluster of states between the West and Midwest.

Map 7. States with Elected Women Serving in Senate in 2016

We can see that a lot has changed in 2016 since 2010. At this time Senator Kay Hutchison from Texas has retired and while Republican women maintain seats in Alaska and Maine, they also acquire seats in West Virginia, Iowa, and Nebraska, While Democrat women have maintained seats in Washington, California, Missouri, New York, Maryland, New Hampshire, Minnesota, and Michigan. They have also acquired seats in North Dakota, Wisconsin, Hawaii, and Massachusetts. At this point though we see that there are no women in Senate in the South, and that cluster in the West remains empty. From this map we can see that there are obvious trends geographically as clusters form in the Northeast and Midwest as well as in coastal Western states and off shore states. At this point though, 2016 has the most amount of states with women as senators.

Map 8. States with Elected Women Serving in Senate in 2019

Finally, as we arrive on our most current map depicting states with elected women in Senate, we see that while the number of states with women serving as Senators has remained, they have moved around the map. As of right now, six states have Republican women serving as Senators and twelve states have Democrat women serving as Senators. While this isn’t the biggest gap we’ve seen, there is still double as many states electing Democratic women than Republican women to Senate. At this point there is a woman Senator in every region of the United States however the largest concentration of states with woman Senators is in the Midwest. At this point there has also been no elected Republican women in Senate for the entire Western continental United States with Texas being as far West as they have made ground.

In the 2018 midterm elections there were five races in which a Republican woman ran in Nebraska, Washington, Tennessee, New York, and Arizona.These five races took place across every region in the United States so through looking at exit polls from these races they can hopefully shed light on the trends among the regions in which they will serve to be a case study. The Senate election in Nebraska was between two women, Republican, Deb Fischer, and Democrat, Jane Raybould. Fischer was the incumbent and was reelected for a second term. Exit polls conducted by Fox News found that as expected from the literature review, more Republican women crossed party lines to vote for Raybould than Democratic women crossed for Fischer. Overall 10% of Republican women said they voted for Jane Raybould while only 5% said they voted for Deb Fischer. Along with this, independent voters were pretty much split with only a one-point difference between the two candidates going to Raybould. Also as expected, 53% of those in urban communities voted for Raybould while 42% voted for Fischer and 43% of those in suburban communities voted for Raybould while 54% voted for Fischer. The biggest difference however was among rural voters where 27% of those from a rural community voting for Raybould and 70% voting for Fischer. The biggest takeaway from this information and how it applies to the Midwest would be that the Midwest follows the trend of having more Republican women cross party lines with their vote than Democratic women and as the Midwest has a lot of rural communities, knowing that 70% of those in Nebraska voted for a Republican women is interesting. However, the biggest limitation in this study along with three other of these races is that they are between two women so it is difficult to distinguish between gender and party and if when two women are running against each other if gender plays as big of a role.

The next campaign in which a Republican woman ran was in the West in Washington where incumbent Maria Cantwell, a Democrat, ran against Republican, Susan Hutchison. Hutchison ended up losing what would have been the first elected Senate seat to be held by a Republican woman in the West. Exit polls conducted by Fox News found that overall the biggest party crossover among party identification and sex was found in Republican men with 9% voting for Cantwell. Independent voters overall however gave 2% more votes to Hutchison than Cantwell. The election ended with Cantwell receiving 58.4% of the vote and Hutchison receiving 41.6% of the votes. Much like in Nebraska as both candidates are women it is a little more difficult to see the effects of having a Republican woman running especially as she ran against an incumbent. However, seeing as she was running against an incumbent, she did do well among Independent voters and Republican women as they had less crossover than Republican men leading me to infer that Republican women are less likely to cross party lines to vote for a woman if both candidates are women.

Tennessee had a very interesting race as it was a Republican woman candidate, Marsha Blackburn, and Democratic male candidate, Phil Bredesen. The most surprising information garnered from looking at exit polls done in Tennessee by CNN News was that of the 37% of voters that said that electing more women to public office was very important, 67% still voted for Bredesen meaning that while Democrats tend to be more likely to believe that electing a woman to public office is important they are not as willing to cross party lines to vote for a woman. This is further shown in that more Republican women crossed party lines to vote for Bredesen than Democratic women did so for Blackburn with 6% of Republican women voting for Bredesen and only 4% of Democratic women voting for Blackburn. Overall, both men and women were more likely to vote for Blackburn, but it was actually closer among women than men. One interesting poll taken that was not found for the other races asked what quality mattered most in the voter’s Senate vote. While 38% of voters said they voted for their candidate because they share the same views of Government 64% of those respondents voted for Blackburn. Only 13% said that they voted for a candidate because it was their party and of that 60% voted for Blackburn as well. 18% cited the candidate’s willingness to compromise as what mattered most with the majority, 69%, of those voting for Bredesen, and 26% said the candidate’s caring about others is what mattered most with 55% of those voting for Blackburn. This statistic was interesting as only 13% said they voted for party alone, but Democrats were not as willing to cross party lines to vote for Blackburn even after finding that they were more likely to find it very important to vote more women in to public office. This race was the most interesting to look at as there was no incumbent and a Republican woman ran against a Democratic man and won by 10.8-point lead.

In New York, Republican Chele Chiavacci Farley ran against incumbent Democrat, Kristen Gillibrand, and lost by a huge 34-point difference. Regardless of gender voters leaned towards Gillibrand as well as Independents and moderates. In this election 49% of voters said it was very important to vote a woman into office and of those, 86% voted for Gillibrand. However, while urban communities overwhelmingly leaned towards Gillibrand, 53% of those in suburban areas voted for Farley which considering she only got 33% of the overall vote is a huge accomplishment. From this I can assume that in New York like in many Northeastern states, the amount of concentrated population in urban communities is swaying the general election outcome while suburban and rural areas remain more conservative.

In Arizona, there was an open seat which Democrat, Krysten Sinema, and Republican, Martha McSally campaigned for. Although Krysten Sinema won in a very close election which had to be recounted, McSalley was appointed shortly after by Governor Doug Ducy following Senator Jon Kyl’s retirement. In exit polls conducted by CNN News, they found that Independent voters regardless of gender leaned towards Sinema. The largest crossover though was from Republican women as 16% voted for Sinema and only 1% of Democratic women voted for McSally. This was the closest race with 50% of the votes going to Sinema and 47.6% going to McSally.

Tentative Conclusions

In my research I was able to identify a number of trends among certain regions in the United States. One of these being that the since my research begins in 1980 there have been no Republican women serving in the Senate in Western United States however numerous Democratic women have served for the Senate. There also seems to be a huge gap in the Northwestern region, excluding Washington, in which nearly no women have been elected to Senate. There has also been a decrease of women serving elected Senate terms in the South however a growth in the Midwest. Among the 2018 elections in which Republican women ran it was a consistent case that Republican women crossed party lines more so than Democratic women however in Washington the group most likely to cross party lines in the past Senate election was Republican men. It was also very interesting to find that Democrats are significantly more likely to find electing a women to public office very important however they are least likely to cross party lines even to vote for a woman.

Research into this topic would greatly benefit from exit polls in future races that are specifically targeted to ask questions about the female Republican candidate and why they did or did not vote for them. Also more recent research is needed into looking at the different political cultures in the United States and how they are developing or shifting over time and what we can expect in future races. Looking forward, if the trends on the maps illustrated were to continue I would expect more Republican women to be elected into Senate from the Southeast and Southwest and eventually move into more Central United States until reaching the West.

Appendix

References

Barnes, Tiffany D., and Erin C. Cassese. 2017. “American Party Women: A Look at the Gender Gap within Parties.” Political Research Quarterly 70, no. 1 (March: 127-41.

Brians, Craig Leonard. 2005. “Women for Women?” American Politics Research 33, no. 3: 357. doi:10.1177/1532673×04269415.

Burrell, Barbara, Susan Carroll, and Kira Sanbanmatsu. 2014. “Men’s and Women’s Presence and Performance in Primary Elections for the U.S. House.” In Gender in Campaigns for the U.S. House of Representatives, University of Michigan Press.

Center for American Women in Politics. 2018. “History of Women in the U.S. Congress.” CAWP. December 04. https://cawp.rutgers.edu/history-women-us-congress.

Center for American Women in Politics. 2019. “State by State Information.” CAWP. March 20. https://cawp.rutgers.edu/state-by-state.

Darcy, R., and Sarah Slavin Schramm. 1977. “When Women Run Against Men.” Public Opinion Quarterly 41, no. 1: 1. doi:10.1086/268347.

Elder, Laurel. 2008. “Whither Republican Women: The Growing Partisan Gap among Women in Congress.” The Forum 6, no. 1. doi:10.2202/1540-8884.1204.

Fox, Richard L., and Jennifer L. Lawless. 2010. “Gendered Perceptions and Political Candidacies: A Central Barrier to Womens Equality in Electoral Politics.” American Journal of Political Science55, no. 1: 59-73. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00484.x.

Fox, Richard L. and Lawless, Jennifer L. 2018. “A Trump Effect? Women and the 2018 Midterm Elections.” The Forum16, no. 4: 569-90. doi:10.1515/for-2018-0038.

Kurtzleben, Danielle. 2018. “A Record Number Of Women Will Serve In Congress (With Potentially More To Come).” NPR. November 07. https://www.npr.org/2018/11/07/665019211/a-record-number-of-women-will-serve-in-congress-with-potentially-more-to-come.

Lieske, Joel. 1993. “Regional Subcultures of the United States.” The Journal of Politics 55, no. 4: 888-913. doi:10.2307/2131941.

Lieske, Joel. 2009. “The Changing Regional Subcultures of the American States and the Utility of a New Cultural Measure.” Political Research Quarterly 63, no. 3: 538-52. doi:10.1177/1065912909331425.

Och, Malliga, and Shauna Lani Shames. 2018. The Right Women: Republican Party Activists, Candidates, and Legislators. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Perry Bacon, Jr. 2018. “Why The Republican Party Elects So Few Women.” FiveThirtyEight. June 25. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-the-republican-party-isnt-electing-more-women/.

Sanbanmatsu, Kira. 2002. “Political Parties and the Recruitment of Women to State Legislatures.” The Journal of Politics 64, no. 3 (August): 791-809.

Sanbonmatsu, Kira, and Kathleen Dolan. 2008. “Do Gender Stereotypes Transcend Party?” Political Research Quarterly 62, no. 3: 485-94. doi:10.1177/1065912908322416.

Thomson, Danielle M. 2015. “Why So Few (Republican) Women? Explaining the Partisan Imbalance of Women in the U.S. Congress.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 40, no. 2: 295-323.

Vega, Arturo, and Juanita M. Firestone. 1995. “The Effects of Gender on Congressional Behavior and the Substantive Representation of Women.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 20, no. 2: 213. doi:10.2307/440448.

Weakliem, D. L., and R. Biggert. 1999. “Region and Political Opinion in the Contemporary United States.” Social Forces77, no. 3: 863-86. doi:10.1093/sf/77.3.863.