#ChurchToo: Religion, Politics, and Gender in the 2018 Midterm Election

Darcy Furlong

Looking at religion and the role of religion in the political arena is clearly not a new topic of study, however, there is far less research done on the interaction of gender, religious affiliation, and voting behavior. The role of religion and politics is of great interest in today’s climate, due to the increasing lack of commitment to the Republican Party by many Catholics, and the rise in “religious nones.” Religion has been a part of the political makeup of our country for years, as the church has long been a place where people congregate to talk about important issues (Ebersole 1960). This chapter is not meant to suggest that religious values and beliefs are more important to the average American than political party (i.e. Republican or Democrat), as party is still the strongest indicator as to how someone will vote (Cohen 2003). However, religion does have some push and pull into what party people identify with in the first place (Farrell 2011). For example, the pro-life movement, which has roots in conservative churches’ messaging is a large reason why some people chose to side with the Republican Party during elections (Brint and Abrutyn 2010). Laws about abortion are a controversial subject, and many highly religious persons claim that they cannot in good standing with God choose to support a political party that accepts legal abortion (Brint and Abrutyn 2010). However, liberal leaning churches (such as some Protestant branches) are likely to support liberal policies, such as more forgiving immigrations laws (Braunstein, Fuist, and Williams 2018). Church’s that supply sanctuary to illegal immigrants from ICE are more likely to hold a politically liberal position, and members of the congregation may feel pushed to side with the Democratic Party because of this (McDaniels, 2008).

In this study, I examine the relationships between gender and voting behavior among Catholics and “religious nones”. I have decided to forgo analyzing Protestants and Fundamentalist Protestants, because there does not appear to be much movement in party choice in these groups. Towards the end of the chapter, I will also explore implications among Jewish voting patterns, however we have less data for this specific group. Although there is not yet data collected regarding Jewish voting choice broken down by gender, I have decided to include this topic due to the increasingly more evident and extreme antisemitic acts occurring since the election of Trump, and in the months before the midterm election.

Some Background

Before exploring my findings, some background knowledge should be understood about the Catholic church’s role in politics, and who exactly the “religious nones” are. The Catholic Church has been under the public’s eye for years, due to their power and high voter turnout come Election Day. Catholics have not always supported the Republicans as fervently as they presently do (Ebersole 1960). However, since 1998 most Catholics who identify as being very committed to the church are registering as Republicans (Miller 2016). Today, Catholics constitute the largest single religion in America, meaning that it is not only important to study the statistics in voter trends and choice, but also the implications behind the choice in vote (Jalen 2003). The Christian Right is often associated with the Catholic Church; however, it should not be assumed that all Catholics are supporters of the Christian Right. The Christian Right evolved in the early 1980’s after the election of President Ronald Reagan. This movement rocketed because of the strong backing of organizations such as the Moral Majority, which was a respected organization that soon became known as the “New Christian Right” (Braunstein et al 2018). Braunstein, Fuist, and Williams (2018) completed a study looking at religion and progressive politics, using the works of Chaves to explore this topic. They found that the best predictors of an individual supporting the Christian Right movement came from frequency of worship services (with more support coming from individuals attending more services), and how literally they read The Bible (Braunstein 2018). This is something to investigate because recent findings show that Catholics who attend more services are less likely to support issues and policies Trump supports (Ekins 2019). For example, members of a Catholic congregation who attend church once or more a week are far more likely to support international trade laws, something that Trump is notoriously against due to his strong “Make America Great Again” message (Ekins 2019). From Braunstein’s studies (2018), one would assume that the more services someone attends, the more conservative they would be. A year later however, Ekins proves that this is not true all the time, highlighting that being Catholic does not tie a person to the Christian Right (Ekins 2019). In my research, I will examine where movement is happening in the Catholic church and speculate on reasons why.

The “religious nones” are an increasingly growing population of voters, which is why I hone in on them in the 2018 Midterm Election (Vargas 2011). Individuals that list themselves as “religious nones” are not currently a part of a church and/or religious practice. An interchangeable term used for this group of people is “religious unaffiliated,” meaning that the person is not attached to a religious group in any way. There are fewer people today who identify with a religion than there once were, and millennials/young people are increasingly becoming more “spiritual” than “religious” (Norris and Inglehart 2004). Examining the term “spirituality” closer, Norris and Inglehart, along with other religious scholars have seen an uptick in millennials stating that they are not a part of a church but believe in a higher power or being (Norris, et. al 2004). The phenomenon behind the increase in “religious nones” has gained much attention from the media, and political figures in today’s political arena. Because of this, it is important to explore some of the demographics of the “nones,” as this information can be pertinent in the explanation of why voting patterns develop the way that they do. Religious nones are slightly less educated, and slightly of a lower economic status than the average US adult over the age of 25 (Kosmin, Keysar, Cragun, and Navarro-Rivera 2009). According to recent reports looking at the impact religious “nones” have on politics and political outcome, between 15 and 18 percent of American’s currently identify as a “religious unaffiliated” person. This is a huge increase from a mere 7% who identified this way in 1991 (Vargas 2011). Vargas (2011) shows that increasing numbers of people are identifying as “religious nones”, and concludes that between 2003 and 2006, 13% of those identifying with a religion considered unaffiliating (although only 40% of those went through with it). Speculating about the growing number of religiously unaffiliated individuals, Hout and Fisher (2014) suggest that “religious nones” are more inclined to lean liberal or moderate. The tendency for “religious nones” to lean left could be good news for the Democratic party in future elections, especially with the increasing number of people unaffiliating.

Method

For this study I compiled data from exit polls and the General Social Survey (GSS) to examine relationships between gender and the most prominent religious affiliations in the US. I was most interested in finding discrepancies between gender, which is only reported for what GSS deems the most prominent religions in America: Protestant, Catholic, Protestant-Fundamentalist, None/religious unaffiliated, and Other. By crossing and comparing various data sets, I was able to see differences in vote choice between men and women in each of these five religions. However, I was most interested in the religions that seemed to have the most movement between the 2016 and 2018 Elections. Specifically, the Catholic Church, and the religious non-affiliated appeared to be the least salient to previous party choice. In this chapter, salience refers to the likelihood a person identifies with the political party most associated with their church. For example, Catholics tend to be Republican (although as we will see this is changing), and religious non-affiliated persons tend to vote Democrat. I speculate implications behind this, and look to popular news sources, and peer reviewed literature to draw some possible causes as to why there seems to be so much movement.

Catholics and The Christian Right: What is Changing?

The Catholic Church has often spoken out against events or people in politics (Miller 2016). The 2018 Midterm Election was unique for many reasons, specifically when examining voting choice by Catholics. There was a drop in Catholics who voted Republican. This finding is important, because it seems to be an indication that people are growing increasingly hesitant to the stance their church has with the Republican Party (Pew 2018).

I examine abortion extensively in this chapter because it is deemed a women’s topic, and so much of the 2018 Midterm election was revolving around women’s issues, rights, and representation (Hayes and Lawless 2016). Abortion is a continuously hot topic amongst religious scholars, especially when debating the role of religion in politics. However, the topic of abortion in relation to politics and Catholicism was not prominent until the 1976 presidential election between Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford (Miller 2016). Abortion was brought up at this time because both candidates sought to gain the Catholic vote by siding and attempting to persuade the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (NCCB) to support their candidacy (Miller 2016). The stance Gerald Ford had on the creation and implementation of anti-abortion laws was ultimately the reason that the NCCB supported him (Miller 2016). However, before 1976, abortion was not discussed between Catholics and the state. Since then, the Catholic church has solidified and externalized their stance on a zero-tolerance policy for abortion and has begun to use their stance on anti-abortion to urge members not to support legislation or candidates who will provide a platform for pro-choice stances (Miller 2016). It should be noted that the Catholic Church currently opposes abortion in all instances, regardless of circumstance. The church has even gone as far as to prohibit any Catholic priest from serving commune to a Catholic Democrat who did not oppose abortion in her campaign (Miller 2016). This last statement refers to pro-choice state senate candidate Lucy Killea. Killea was met with opposition from the church due to her stance, denied communion, and was targeted by the church in public speeches such as ones by Archbishop O’Connor.[i]

Abortion is a fairly “easy” topic to look at when examining and exploring the Catholic church, and their saliency to the Republican party due to their pro-life standings (Calfano 2010). By “easy,” it means that it is usually a high-profile topic, and it is something that voters easily understand. More specifically, the public typically knows what abortion is and how it works but does not necessarily know how “political” legislation works (Carmines and Stimson 1980). This is relevant in accordance with research done about how important a candidate’s religion is to voters. It is not that people tend to vote for a candidate because of their religion, but rather people tend to make assumptions about a person’s standings on certain issues due to what religion they associate with (Simas and Ozer 2017). Simas and Ozer found that if a Democratic Catholic was running, most people would assume the candidate opposed abortion; even though the Democratic Party is pro-choice (Simas et.al 2017).

Thus far, it seems relatively apparent that the Catholic Church as an institution does not support the pro-choice movement. In one study done by Lipka in 2013, he found that opinion polls have consistently found that only 13% of lay Catholics[ii] supported their churches conservative, and unforgiving stance on abortion (Lipka 2013). This relatively low number of supporters is not something to ignore, as it implies there is something happening between the messaging the Catholic Church sends to their members, and the way the members are receiving and/or applying said messaging.

2018 was the year of the woman for many reasons, and with this, came the increase in conversation revolving around women’s issues. One of these issues was abortion. President Donald Trump was one of the key figures in the increase of discussions revolving around abortion and spending government funding’s in accordance with Title X[iii] (Watson 2018). With President Trump’s more radical appeals on abortion, came the support of Pope Francis on October 10th, 2018, mere weeks before the revolutionary midterm election. Pope Francis and Donald Trump have not had an easy relationship, as the Pope has tweeted multiple times disagreeing and calling President Trump out for cruel and “unchristian” legislation (Burke 2017). Most specifically, the Pope does not agree with President Trump’s stance on immigration and tight border control, tweeting: “How often in the Bible [does] the Lord asks us to welcome migrants and foreigners, reminding us that we too are foreigners!” (Burke 2017). However, the Pope does agree with President Trump on one thing: abortion. Before the midterm election, amongst the fury of the #metoo movement, #churchtoo movement (a spinoff of the #metoo movement created by active Christian women), and other sexual assault violations/misconducts, Pope Francis took the chance to remind people that abortion is still wrong, comparing it to “hiring a hitman to solve a problem” (Guiffrida 2018). Polls showed after the Midterm Election, 42% of Catholics opposed abortion in all or most cases. However, this is a notable drop from 45% in 2009 (Pew Research 2009). This means that either the Pope’s statement had little to no effect on the relative population of Roman Catholics, or abortion is not a driving factor determining voting choice. Although abortion is not the only legislation that the Catholic church speaks out about politically, it is a topic that many people regard as being influenced by religion, and this is confirmed by researcher Calfano when looking at religious groups, and how they have branded or coined the term “pro-life” to mobilize their stance in politics (Calfano 2010).

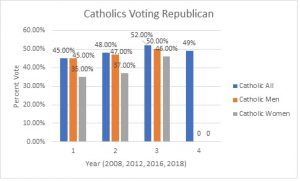

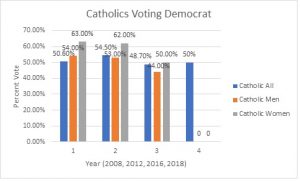

Now that I have looked at one of the hottest topics amongst conservative and Republican leaning churches, we can use Figure 1 to look at some shorter-term statistics about voting patterns (Miller 2016). As shown, there is an increase between Catholic women who voted for McCain over Obama in 2008, and women who voted for current President Donald Trump in 2016. As shown in, there was about the same amount of support for Obama in his second term, but a slight increase in the Catholic women’s vote for Republican candidate Romney. Romney was often scrutinized over his religious affiliation with the Mormon church, thus developing some tension between Catholics and him. This was because some Catholics deemed him as being “anti-Catholic”, which interestingly did not contribute as a factor to loosing Catholic support in the 2012 race (Meyers 2012). However, most interestingly was the percent increase from 2008 to 2016 in Catholic women supporting the Republican candidate. In a relatively short amount of time (meaning two terms), Catholic women shot up a whole 9% in their support for Trump. This increase could be contributed to several factors, and although we cannot make any causal claims due to the nature of this study, we are able to speculate about potential factors that played a role in the significant increase.

Figure 1. Catholic Voting Patterns, 2008-2018

There were several Catholic churches across the nation that outwardly spoke against Hillary Clinton as a candidate (Vicker and Luke 2016). Some churches even went to the extremes of sending out online bulletins and brochures linking Clinton with Satan, remarking that “it is mortal sin to vote Democrat [in this election]” (Vicker and Luke 2016). Although not all Catholic churches went to these extremes, the ones that did could have played a role in the increase in Catholic Voters (including women) who voted for Trump. However, what happens in 2018 (regardless of gender) is that there was a decrease in Republican support, and an increase in Democrat support. This is engaging information to inquire about, especially because the Catholic church supported Trump in the months before his election. However, during Trump’s first 100 days of President, many Bishops began to remark that Trump’s actions on things such as immigration were “discriminatory” and “anti-Christian” (Gaffy 2017).

One significant thing that many Catholic women partook in during the #MeToo movement after the election of Trump, was creating a spin off hashtag for the individual experience of women in churches who have faced sexual abuse, misconduct, or harassment. This hashtag, although underrepresented and under reported by the media was called #ChurchToo (Kivi, 2018). This hashtag grew rapidly in the Catholic world of social media, and it was used as a tool to exploit the often unethical and inappropriate actions that some individuals in the church partake in (Kivi, 2018). In 2018, there was an increase in stories revolving around men in high authority in the church abusing their power through acts of sexual misconduct (Horowitz and Povoledo, 2019). Probably most predominately were the sexual misconduct allegations against previous Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, leading him to step down from his cardinal position (Povoledo and Otterman 2018). In addition, there was the now infamous story that sparked concern revolving around the sexual assault allegations in Pennsylvania (Goodstein and Otterman 2018). With months before the midterm election, and news surfacing that the Roman Catholic Church helped cover up more than 300 priests sexual assault accusations, both the media, and members of the Roman Catholic Church spoke out against the actions taken by the Church (Goodstein and Otterman 2018). It could be that women in the Catholic church who previously identified Republican are dis-identifying with the political party in disgust and disagreement about the recent stories surfacing. The Democrat and Republican party have both been actively speaking out against the horrible acts that have been highlighted since the #MeToo movement, but Donald Trump has not always made comments that please people, saying things such as “When you are rich, you can do whatever you want to women” (Cillizza 2017). Comments such as these could be a contributing factor in the switch from Republican to Democrat. We do not yet have the breakdown of Catholic vote by gender for the most recent 2018 Midterm Election, but it will be interesting to see if more women have disaffiliated with the Republican Party since the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

All Jews are Democrats (NOT!)

Although there is not yet available data on the breakdown of gender regarding Jewish voters in 2018, I have chosen to include a subsection due to the saliency many Jews have to the Democratic party. Since 1961, Jewish voters have been split about 75% Democrat and 25% Republican (Pew, 2016). Due to the already relatively small percentage of Republican Jews, it is imperative that we explore possible motives as to why previous Republican Jews are choosing to vote Democrat instead. Like other religious minorities in America such as The Church of Latter Day Saints (previously called Mormons) and Evangelical Christians, Jewish voter turnout on election days are typically much higher than others. Similarly to the support Mormons give the Republican party, Jews offer the same support for the Democratic Party. With the growth of Jews voting Democrat, this could be a huge win for the Democratic party.

Using the national exit polls, we can see that in 2016, 24% of Jews voted for Trump, and 71% voted for Clinton. However, in 2018 these numbers became more polarized, with 79% of Jews voting Democrat, and only 17% voting for the Republican party. Although the percentage voting Republican is within a five-percentage margin since 2000, I am interested in how quickly the number dropped in Republican Jewish supporters from 2016 to 2018 (Smith and Martinez 2016). Political party, as we have clarified earlier, is often an area where people stay faithful to the same party over a lifespan (Ebersole 1960). Making the shift to vote for the opposite party in which one typically supports is a big deal, especially because electoral success really depends on maintaining relationships and coalitions with different groups (i.e. different religious groups) (McDaniel and Ellison, 2008). Another more basic (yet extremely important) reason why the Republican party may be weary of the shift in Jewish support is because currently about 25% of donations to the Republican party come from Jewish people and/or corporations (Windmueller, 2016).

There has been an increase in synagogues who are listing themselves as “Sanctuary Synagogues” to protect illegal immigrants from being deported since President Trump and ICE have cracked down on illegals (Karol, 2017). One of many examples is a Synagogue in Sacramento, California, whose leader choose to push her congregation to invite illegal immigrants into their place of worship to keep them safe (Karol, 2017). Congregation President Alan Steinberg talked to a reporter, emphasizing the importance of using their place of faith to keep others safe. When interviewing a Holocaust survivor in the congregation who was an avid supporter of the movement towards sanctuary, he stated that the “current state of affairs takes me back to 1939” which is why he felt the need to help others in a similar situation (Karol, 2017). This is another example of how religious groups get involved in political climate and action, and why Churches, Synagogues, and other places of worships are important to study.

Although not necessarily a causal relationship, there were a few things that happened between the election of Donald Trump in 2016 and 2018 that seem to directly affect the Jewish population. For example, half way through 2017, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reported that there was an 57% increase in anti-Semitic hate crimes and incidents since the election of Donald Trump (Goldberg, 2017). In the same ADL report, researchers concluded that the heightened political atmosphere, and the mobility Trump has given to radical political players has directly and indirectly contributed to the rise in Antisemitism (Goldberg, 2017). This rise, although it may not have a direct impact on the decrease in Jewish support for the Republican Party, it very well could have. On the other hand, the Trump administration has supported Israel more than any other previous U.S. government, which could combat and counteract some of the negative events occurring around the Jewish population in the United States, and the Trump Administration’s response to them (Wilkonson 2018). However, until an empirical study is done directly looking at Jewish voters in the 2018 election and reasons behind the shift in voter choice, we cannot conclude anything. Another moment before the election 2018 that could have affected Jewish voters’ opinion of the president and the Republican party was Trump’s seemingly insensitive and harmful comment made after the incident in Charlottesville, Virginia. After white supremacists gathered in Virginia, using Nazi jargon and holding signs claiming, “Jews will not replace us,” President Trump responded by saying “you had people that were very fine on both sides”, seemingly justifying the anti-Semitic attacks (Vidal, 2018). Finally, one of the most infamous events that occurred weeks before the midterm election was the horrific shooting at a Synagogue in Pittsburgh, killing eleven people, and wounding six more. With this event happening so close to the midterm election, it could have spiked a response in the Jewish population. Not only did this event bring up more conversation about Trump mobilizing anti-Semitic behavior, but it also shed light on the (lack of) gun regulations. President Trump has been notorious for supporting the NRA since his presidency, even with the increase in mass shootings and American initiated terrorist attacks. When looking at gun control among men and women, a report done three months before the 2018 Midterm election concluded that 69% of women wanted stricter gun laws, as opposed to 47% of men. Because women statistically are less likely to support Trump’s stance on gun laws, The support of access to guns that Donald Trump presents in legislation could be a factor leading to the decrease in Jewish support in the Midterm, as their population was directly affected by the increase in guns (Delkic, 2017).

The “Nones” Matter!

Because millennial voter turnout was stronger than it has ever been before (in previous midterm elections that is), the 2018 Midterm Election could be an explanation as to why the percentage of “religious nones” also increased (Pew 2018). Typically, younger people have more liberal views on topics that the church on average has more conservative views about. These topics include policies often supported by more liberal leaning churches (i.e. some Protestant branches) such as immigration, health care, education, and of course, abortion/women’s health services (McDaniel, et.al 2008). One explanation to the increase in the amount of people registering as not being affiliated with any religion could be due to the less stigmatized association, and lack of religion than there historically has been (Braunstein, et.al 2018). The Pew Research Center predicts that if current trends continue, the nation may experience a shift in religion and party affiliation over the next decade (Pew 2017).

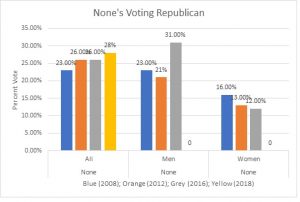

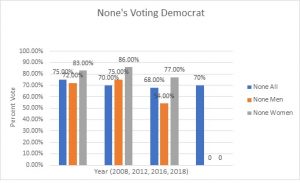

Looking at Figure 2, we can see that there has been a steady increase in “religious none’s” supporting the Republican party since 2008 regardless of gender. In addition, Figure 2 also shows a steady increase in “religious nones” supporting the Democratic party. However, it should be noted that in the 2016 election, more than one quarter of the voters supporting Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton were registered as “religious nones” (Pew 2017). Looking at Figure 2 we can see the differences between voter choice, and gender in similar ways that Figure 1 illustrates above. Something to draw attention to should be the difference in men and women who supported Donald Trump in the 2016 election. Since 2008, there has been a steady uptick in religious nones voting for the Republican candidate and/or party, but in 2016, only 12% of women not identifying with a religion supported Donald Trump. This is interesting because 31% of men did, creating a gender gap . This gender gap implies that women nones disapproved far more of Donald Trump than their male counterparts. However, in relation to nones voting Democrat, the Republican nones consist of a relatively small group of people.

Figure 2. Religious “Nones” Voting Patterns, 2008-2018

Kosmin (2009) pursued research looking at the uptick in religious nones through analyzing census data and looking at past and current religious affiliation. Looking specifically at the Midterm election in 2018, we can look at implications from the data we have thus far. Although we do not have a breakdown by gender, we are able to see that regardless of gender in 2018, religious nones voted slightly more for the Democratic party than they did in 2016. This is interesting because although there was a slight increase in support for Republican Party as well in 2018, there was still 83% of nones voting Democrat. It will be interesting to see when this data is available for gender if both men and women were more inclined to support the Democratic party in the 2018 Election, or if there is a large gap between gender similarly to 2016.

Some Common Ground and Final Thoughts

Catholics and religious nones have more in common that one might think at first thought. More specifically, Catholics are the most prone today to disaffiliate with their religion. These finding are articulated through research done by Kosmin in 2008. Kosmin found that at the age of twelve, 24% of adults in 2008 said they identified as Catholic; of this group, 35% now do not identify with a religion (Kosmin et. Al 2009). Out of all the religious groups studied[iv], the children who identified as Catholic at the age of twelve were more likely to identify as a “religious none” as an adult. This is interesting for a multitude of reasons, but regarding politics it is interesting because Catholics are known to be split very evenly between both parties, and none’s are more inclined to vote Democrat. Taking this research to the next level, it would be interesting to see if the Catholic’s who dropped their religion as adults were registered Democrat or Republican, and if there was a gender difference in who is disaffiliating. The Catholic church is currently under fire for having sexist tendencies, such as not allowing women to hold high positions of authority, and this may push some women away from the church as an institution (Ferree and Martin 1995).

Another more long-term implication of the disaffiliation with organized religion among our current generation, especially in the younger generations is that people are not going to the social, community-based sermons anymore (Ham and Foley 2016). The implications behind this is that people are no longer talking about policies, morals, and morality in politics as much as they used to (Ebersole 1960). With the decrease in attendance of church services where opinions are often talked about prior and post sermon, and a decrease in the importance religion holds in our society, many people may be less likely to speak about politics in person (Ham and Foley 2016). Instead, we have Facebook and Twitter pages where like-minded people come to share the same opinions, getting conformation of their ideas about politics, but not necessarily being exposed to a variation of perspectives.

It is important we continue to study the relationship religion and politics have, and if that relationship is changing, especially among women voters. By analyzing data broken down by gender, political affiliation, and religion, we are able to see interactions that gender plays in voter choice. In the 2018 Midterm election, it is apparent that Catholic and religious none women supported the Democratic party more than they did in the 2016 election. Men that originally voted for Donald Trump in the religious none group also switched to the Democratic party in the 2018 Midterm election. There are many relationships that we can look at, and reasons why men and women seem to have different perspectives on politics, in accordance with religion. However, this is a preliminary study, with limited resources and data sets. I urge people interested in this topic with more resources to look more specifically at how men and women are voting over time, especially in some of the smaller more marginalized religions.

References

Brint, Steven, and Seth Abrutyn. 2010. “Whos Right About the Right? Comparing Competing Explanations of the Link Between White Evangelicals and Conservative Politics in the United States.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, No. 2: 328-50.

Braunstein, Ruth, Todd Nicholas Fuist, and Rhys H. Williams. 2018. “Religion and Progressive Politics in the United States.” Sociology Compass, No. 2.

Calfano, Brian Robert. 2010. “The Power of Brand: Beyond Interest Group Influence in U.S. State Abortion Politics ” Journal of State Politics and Policy Quarterly 10 (3): 227-247.

Carmines, Edward G., and James A. Stimson. 1980. “The Two Faces of Issue Voting.” American Political Science Review, no. 01: 78-91.

Delkic, Melina. 2017. “Women Want Gun Control More than Men, a New Poll Shows.” Newsweek. December 20. https://www.newsweek.com/women-want-gun-control-more-men-753999.

Djupe, Paul A., Jacob R. Neiheisel, and Anand E. Sokhey. 2017. “Reconsidering the Role of Politics in Leaving Religion: The Importance of Affiliation.” American Journal of Political Science 62, no. 1: 161-75.

Ebersole, Luke. 1960. “Religion and Politics.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, no. 1: 101-11.

Farrell, Justin. 201.. “The Young and the Restless? The Liberalization of Young Evangelicals.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, no. 3: 517-32.

Giuffrida, Angela. 2018.”Pope Francis Compares Abortion to Hiring a Hitman.” The Guardian. October 10. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/oct/10/pope-francis-compares-abortion-hiring-hitman.

Goodstein, Laurie, and Sharon Otterman. 2018. “Catholic Priests Abused 1,000 Children in Pennsylvania, Report Says.” The New York Times. August 14. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/14/us/catholic-church-sex-abuse-pennsylvania.html.

Ham, Ken, and Avery Foley. 2016. “Pew Research: Why Young People Are Leaving Christianity.” September 08. https://answersingenesis.org/christianity/church/pew-research-why-young-people-leaving-christianity/.

Jelen, Ted G. 2003. “Catholic Priests and the Political Order: The Political Behavior of Catholic Pastors.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, no. 4: 591-604.

Kahl, Sigrun. 2005. “The Religious Roots of Modern Poverty Policy: Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed Protestant Traditions Compared.” European Journal of Sociology, no. 01: 91.

Kivi, Lea Karen. 2018. “#ChurchToo: How Can We Prevent the Abuse of Women by the Clergy?” America Magazine. November 16. https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2018/11/16/churchtoo-how-can-we-prevent-abuse-women-clergy.

Lipka, Michael, and Michael Lipka. 2014. “Majority of U.S. Catholics’ Opinions Run Counter to Church on Contraception, Homosexuality.” Pew Research Center. February 07. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/19/majority-of-u-s-catholics-opinions-run-counter-to-church-on-contraception-homosexuality/.

Mcdaniel, Eric L., and Christopher G. Ellison. 2008. “Gods Party? Race, Religion, and Partisanship over Time.” Political Research Quarterly, no. 2: 180-91.

Mcfarland, Michael J., Jeremy E. Uecker, and Mark D. Regnerus. 2011. “The Role of Religion in Shaping Sexual Frequency and Satisfaction: Evidence from Married and Unmarried Older Adults.” Journal of Sex Research, no. 2-3: 297-308.

Miller, Patricia. 2016. “The Catholic Bishops and the Rise of Evangelical Catholics.” Religions, no. 1: 6.

Povoledo, Elisabetta, and Sharon Otterman. 2018 “Cardinal Theodore McCarrick Resigns Amid Sexual Abuse Scandal.” The New York Times. July 28. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/28/world/europe/cardinal-theodore-mccarrick-resigns.html.

Setzler, Mark, and Alixandra B. Yanus. 2016. “Evangelical Protestantism and Bias Against Female Political Leaders.” Social Science Quarterly, no. 2: 766-78.

Simas, Elizabeth N., and Adam L. Ozer. 2017. “Church or State? Reassessing How Religion Shapes Impressions of Candidate Positions.” Research & Politics, no. 2

Smith, Gregory A., Jessica Martínez, Gregory A. Smith, and Jessica Martínez. 2016. “How the Faithful Voted: A Preliminary 2016 Analysis.” Pew Research Center. November 09. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/09/how-the-faithful-voted-a-preliminary-2016-analysis/.

Watson, Kathryn. 2018. “Trump Emphasizes Importance of 2018 Victories to Abortion-opposing Group.” CBS News. May 23. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-speaks-to-abortion-opposing-group-live-updates/.

Notes

[i] “…where Catholics are perceived not only as treating church teaching on abortion with contempt but helping to multiply abortions by advocating legislation supporting abortion or by making public funds available for abortion… bishops may consider excommunication the only option” -Cardinal John O’Connor

[ii] Lay Catholics consist of any member of the Roman Catholic Church who has not been ordained (i.e. any Roman Catholic who is not a priest

[iii] President Donald Trump and his cabinet proposed in 2018 legislation that would prohibit any Title X money going to abortion clinics, or clinics that gave information about abortions

[iv] Religious groups studied included: None, Catholic, “Christian”, Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran, Protestant, other