She Debates Like a Guy! Preforming Gender in the 2018 Midterm Senatorial Debates

Lauren Fisher

The guiding research question of this paper is “How did candidates perform gender in the 2018 Senatorial debates in the 2018 midterm elections?” Employing a sample of 20 2018 Midterm Senatorial debates, 5 female v female debates, 8 male v female debates, and 7 male v male debates I conduct a content analysis to distinguish differences, trends and outliers in candidates’ gender performance. I find significant trends in masculine style gender performance across all measures, except for “Self-Promotion,” yet the context of this analysis may potentially explain the discrepancy. When using this information to infer the associations to the Year of the Woman, I found it extremely important to look objectively at gender and not sex. Gender will be an inclusive term that I utilized to understand how candidates perform gender, rather than their sex. Applying this new method of research to a gender content analysis to assess the performance of gender rather than coding for sex, allows the researcher to evaluate the language regardless of the issue. This increases the reliability of the evaluation of gender, further limiting third party variables.

Previous Research and Methods of Gender Communication vs Gendered Communication

Gender Context Analysis

In Beasley’s opinion, gender and communication research has a major problem: having no name. Beasley argues that social scientists who wish to study gender communication within political science remain rooted within campaign and political discourse. Moreover, within this nameless discipline, when gender communication and political science interconnect, scientists equate politics with “elections” and gender with “women.” This method of research is restrictive unless we “transcend our distinctive vocabularies and assumptions in order to speak to each other across methodological and epistemological divides” (Beasley 2006, page 209). This notion of transcending our vocabularies and assumptions allows political scientists to better engage in gender research beyond notions of sex.

Previous research on gender within politics has focused on the differences between candidates within their campaigns. Hayes and Lawless argue there is little evidence of differences within gender communication among 2014 midterm candidates. Hayes and Lawless performed content analysis research that explores the campaign communication by male and female candidates. Their content analysis coded tweets and campaign ads. Their research reports that there is little difference on the issues women and men speak about, the communication techniques they employee, or their personal traits, unbending to any stereotypical sex portrayals. Hayes and Lawless found that party plays a significant role in deciding issues and communication rather than sex nor gender (Hayes and Lawless 2016). This content analysis provides a method of coding that is applicable to many research designs, although Hayes and Lawless oriented their research to focus on campaigns and political discourse thus lacking the transcendence Beasley holds of high importance.

The study of political debates is one that does not necessarily include communication research. Hart and Jarvis researched electoral debates in comparison to other forms of campaign messaging. Hart and Jarvis emphasize the appeal of debates in their findings. Debates are important to research, because they ground the candidates in political discourse and enhance the differences (Hart and Jarvis, 1997). They note that campaign ads adopt the popular national themes and local contexts, which could be a factor in the lack of differences between genders in Hayes and Lawless’s research. The use of tweets and campaign ads is not as useful of a tool when analyzing the performance of gender when compared to the raw introspectively of debates. Political debates hold a higher organic and authentic style of speech and person to person interactions, that does not occur in a manufactured ad or exercised speech. Beasley would agree that debates create a more inclusive method to analyze gender rather than sex. Beasley’s goal of transcending the limitations reliant on political issues and assumptions would be attained if the methodology of Hayes and Lawless was applied to Hart and Jarvis’s research sampling of political debates.

Rather than researching electoral debates, Kathlene analyzed 12 transcripts of state legislative committee hearing debates for gender communication. Rather than candidates, this research focused on the conversation between committee members, witnesses, chairs, and sponsors. While accounting for political and structural factors, Kathlene found that the sex differences between committee members are highly significant. The findings suggest that as the proportion of women increase in the legislative body, the men become more verbally aggressive and controlling within the debate (Kathlene 1994). Although the goal of this research was to understand gender power differences, the utilization of debates was a major component to understand that despite their numerical gain, women are disadvantaged in committee hearings, because they are unable to participate equally. Kathlene provides resourceful content analysis that employed debates as the base of analysis to achieve a well rounded and inclusive form of communication research.

Another example of a gender context analysis, compiled of congressional speeches from the 101st to the 110th Congress (1989–2008) examined gender differences in language within political debates. Yu found that female legislators’ demonstrated both a feminine language style and a masculine language style. For example, a feminine style was identified as higher use of emotion describing words and a masculine style would use fewer personal pronouns and longer words. One limitation Yu noted was the question of whether speeches authentically represent the speakers’ language styles (Yu 2013). Yu questioned the authenticity of the speaker’s remarks in house floor debates, because as Yu notes, congressman and congresswoman generally well-prepared and may ascribe their speech to fit a public image they wish to portray. These limitations accompany the sphere of politics, therefore although a debate, the patterns found in Yu’s research may not be applicable to other communication contexts. This limitation ascribes to Hart and Jarvis’s importance of employing objective content gender analysis in the forms of debates.

In 2018, coined by the media and politicians as “Year of the Woman,” more women than ever have participated in the midterm elections. Kathlene found a disadvantage to women after researching the content of Senate committee hearing debates. Although seemingly a great time for women in politics, such associations can be discovered through objective gender analysis using the methods and tools implemented and advised from the previously mentioned authors.

Research Strategy and Evaluation

One study that researched gender differences in language utilized a technological form of context analysis. By using a computer text analysis program, the study was able to standardize 74 linguistic categories from a large archive of over 14,000 text files of books, poems, song lyrics, and other art forms. This form of gender context analysis allows researchers to observe gender differences on a much larger scale. The findings concluded that females use more words related to psychological and social thoughts while males used more object properties and impersonal topics. This study found that linguistic styles were consistent across different contexts. (Newman, Groom, Handelman Pennebaker, Table 3, page 228). Although this form of gender context analysis compensates for Yu’s apprehension of the authenticity and the applicability in other communication contexts, it does not provide content validity to political debates, that of which the senatorial women candidates engaged within the 2018 Midterms Elections.

Stubbs expands on the implications of words and phrases, such as the meaning of “Gossip” is identified as a women connotation (Stubbs 2001). The understanding of the meanings habitually used in such phrases will greater help code the language used in senatorial debates. Ifechelobi and Ifechelobiis of Nnamdi Azikiwe University expand upon gender discrimination through language and identifies derogatory words against women based on sexuality. They list derogatory words and phrases based on behavior, sexuality, intelligence, emotions, achievements, and appearance (Ifechelobi and Ifechelobiis 2017). For example, “Gossips” is a derogatory word based on behavior and sex. This method of coding derogatory phrases is a form of gender content analysis. This provides an important distinction between gender and sex, as the latter should be transcended as stated by Beasley. Ifechelobi and Ifechelobiis use both gendered categories of analysis and sex-based linguistic forms of analysis. To perform an objective gender context analysis to understand how someone performs their gender, only the gender-based categories be employed.

Krolokke and Sorensen expand gender discourse styles used by men and women. For example, a masculine style will utilize longer messages rather than shorter messages. In addition, Krolokke and Sorensen break down feminine and masculine styles of depicting gender. Feminine styles include indirect, collaborative, and supportive feedback while masculine styles include direct, confrontational and aggressive interruptions (Krolokke and Sorensen, 2006, page 111). Additionally, Wood expands on gendered communication practices explaining how and why women’s speech and men’s speech have these established styles (Wood 1997 page 70). Knowing the origins and methods of these styles will allow for accurate masculine and feminine coding.

Performing Gender

Research has been done on how gender interacts with politics. Sanbonmatsu and Dolan find that within the scope of the political climate, gender stereotypes are somewhat different for Democratic and Republican women. They found that women and men are perceived as possessing different competencies based on the issue. Additionally, women will have to anticipate how these influences might shape their candidacies (Sanbonmatsu and Dolan 2009). This awareness is a notion that can factor into the linguistic styles of each candidate. This is something at Yu would have attributed to the inorganic notions of being a public political figure. One example of this awareness can be seen in Jones’s research. Jones utilized political communication and linguistics to examine whether Clinton talked “like a man” during her political career and campaigning by conducting a quantitative textual analysis of 567 interview transcripts and candidate debates between 1992–2013. The results indicate that Clinton’s linguistic style grew increasingly masculine over time, as her involvement in politics increased. Clinton was performing a masculine gender through her linguistic style (Jones 2016). Yu’s apprehension of an inorganic performance of gender is more concerning if one were to use this method to measure Clinton’s gender style of herself as a person, not as a candidate. Measuring her gender performance as a candidate, via campaigning and debates is a valid tool of measurement as shown in Jone’s research.

The heightened sexist language seen throughout the 2016 election is substantiated by Wilz analysis of the sexist critiques of female politicians in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Misogynistic attacks were viewed throughout the internet. President Trump’s use of the phrase “women card” is an example of gender-based issues, but Wilz agues to not assume all misogynistic issues are rooted in sexism, because if we do, it will undermine the real sexist challenges (Wilz 2016). Sexism, blatant or not is a performance of gender as well. The 2018 Midterm Elections in many ways acted as a response to the political climate of the 2016 Presidential Election. This notion is important to note when coding gender performance. It is here that lies the difference of maintaining the divide from “Gender” communication and analyzing “Gendered” communication. It does not impact the coding of gender performance in context analysis of debates, but provides a larger and nuanced context to analyze the findings.

Research Design

Sample

Employing a stratified and judgmental sample, I chose 20 2018 Midterm Senatorial Debates to code. I chose 5 female versus female senatorial debates, 7 male versus male debates, and 8 male versus female debates. The female versus female debates were chosen from a very limited sample. The male versus male and male versus female debates were chosen by considering swing states and highly anticipated races. These senatorial debates are compiled in a spreadsheet in order to code accurately.

From having to draw from an already small sample of debates, I only found 5 woman v woman debates, thus I included all of them. Considering that each debate is one hour long and each debate requires reviewing multiple times, I decided to choose 20 as my sample size. Therefore, I had 15 debates left to choose to be either male v male or male v female. I decided to choose 7 male v male and 8 female v male, because I wanted a larger sample to include both sexes. A larger sample provides more credit for the frequencies found. Moreover, I am particularly interested in the differences I find within female and male debates. I chose the cases of each category by first choosing swing states and highly anticipated races, then I chose races seen as safer seats second, in order to have a breadth of examples within my research. (See Appendix A for the data spreadsheet and a list of the debates used).

Method

I look objectively at gender and not sex. Gender will be an inclusive term that I utilize to understand how candidates perform gender, rather than their sex. Applying this new method of research to a gender content analysis to assess the performance of gender rather than coding for sex, allows the researcher to evaluate the language regardless of the issue. This increases the reliability of the evaluation of gender, further limiting third party variables.

After analyzing the literature, I compiled the most relevant categories to potentially arise in debates which scholars have used as determents to define masculine and feminine styles. Relevant statements the candidate employs will be coded within one of ten categories. Within these ten categories, five are masculine and five are feminine.

| Masculine Style | Feminine Style |

|---|---|

| Strong Assertions | Emotional Statements |

| Exclusive Statements | Inclusive Statements |

| Self Promotion Statements | Appreciation Statements |

| Negative Statements | Optimistic Statements |

| Rhetorical Statements | Friends/Family References |

In addition to these ten categories, I have chosen to code for interruptions as well. Interruptions are not included within the masculine style quantitative data, because this category received few counts and is considered an outlier. Although it is not included in the masculine style of quantitative data, interruptions are important to note, because it put their opponent at a disadvantage. In addition to the name of the candidate, I note their party identification, age and if they are an incumbent running for reelection. In addition to the measures and personal information, I include anything significant that does not fit within a category into “notes” at the end of the spreadsheet. (See Appendix B for the coding scheme).

In order to combat redundant speech tendencies, I coded each tally by topic. For example, to code for “Inclusive Statements,” a candidate may say, “Climate change will affect all of us. We all have a responsibility to make changes in our lives for the betterment of our environment. If we do not make these changes, who will?” Rather than coding this as five, I would count this as one. Another caveat I was aware of when coding is to only code a statement in a single category. A statement may fit into more than one category, but it is up to the researcher to determine which category it most belongs in.

Limitations

These findings are preliminary due to the use of a small sample in addition to employing judgment to choose the sample. This is a limitation causing low generalizability. Additionally, the use of high-profile races may cause unintended third-party variables that may skew data.

It is important to recognize the categories that comprise the Feminine Style and the Masculine Style are not 1:1, meaning they are not mirrored opposites of each other. The categories that make up the styles are based on research, but the inclusion of which I used was up to my discretion. By choosing an even number to compare, as well as including the categories that would most likely come up in a debate, I catered the method to this research. Although the methods produce strong content validity and construct validity, the amount of researcher preference may lower the reliability. The overall coding scheme has a certain level of subjectivity depending on the category. If this method was replicated the overall trend and frequencies will be similar, due to the carefully outlined coding scheme, yet the statements that are chosen by the researcher and to a certain extent the code the researcher categorizes the statements within, will include human discretion.

Findings

Debate Type

The three types of debates that were coded are 5 female v female, 8 male v female and 7 male v male debates. Every candidate has a percentage of both Feminine Style gender performance and a Masculine Style gender performance. The higher of the two values will be the categorization the candidate will receive. For example, Elizabeth Warren received a Feminine Style score of 11 and a Masculine Style score of 39, therefore Warren will be coded as having a Masculine Style. Overall, 20% (8) of the total candidates were coded as having a Feminine Style of gender performance and 80% (32) of the total candidates were coded as having a Masculine Style of gender performance.

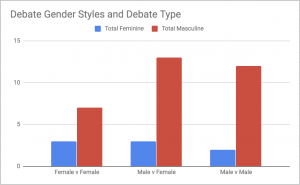

Figure 1. Debate Gender Style and Debate Type

Overall in every debate type, a significantly higher number of candidates employed a Masculine Style of gender performance. In female v female, there were 30% of the candidates debated in a feminine style and 70% of the candidates debated in a masculine style.

| Candidate | Age | Incumbent? | Party | Total Feminine | Total Masculine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyrsten Sinema | 42 | No | D | 27 | 23 |

| Martha McSally | 53 | No | R | 24 | 31 |

| Tammy Baldwin | 57 | Yes | D | 19 | 21 |

| Leah Vukmir | 60 | No | R | 18 | 29 |

| Deb Fischer | 68 | Yes | R | 25 | 15 |

| Jane Raybould | 58 | No | D | 19 | 29 |

| Maria Cantwell | 60 | Yes | D | 12 | 29 |

| Susan Hutchison | 65 | No | R | 17 | 28 |

| Tina Smith | 61 | Yes | D | 13 | 15 |

| Karin Housley | 55 | No | R | 18 | 13 |

In male v female, 18.75% of the candidates debated in a feminine style and 81.25% of the candidates debated in a masculine style.

| Candidate | Age | Incumbent? | Party | Feminine Total | Masculine Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heidi Heitkamp | 63 | Yes | D | 13 | 40 |

| Kevin Cramer | 58 | No | R | 7 | 26 |

| Dean Heller | 58 | Yes | R | 23 | 42 |

| Jacklyn S. Rosen | 61 | No | D | 34 | 31 |

| Dianne Feinstein | 85 | Yes | D | 11 | 13 |

| Kevin de León | 52 | No | D | 20 | 17 |

| Mazie K. Hirono | 71 | Yes | D | 4 | 19 |

| Ron Curtis | 56 | No | R | 3 | 17 |

| Elizabeth A. Warren | 69 | Yes | D | 11 | 39 |

| Geoff Diehl | 50 | No | R | 11 | 23 |

| Marsha Blackburn | 66 | No | R | 14 | 33 |

| Phil Bredesen | 75 | No | D | 13 | 18 |

| Cindy Hyde-Smith | 59 | Yes | R | 15 | 33 |

| Mike Espy | 65 | No | D | 11 | 19 |

| Debbie A. Stabenow | 68 | Yes | D | 22 | 17 |

| John James | 37 | No | R | 14 | 33 |

In male v male, 14.28% of candidates debated with a feminine style 85.7% debated in masculine style.

| Candidate | Age | Incumbent? | Party | Feminine Total | Masculine Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rick Scott | 66 | No | R | 14 | 23 |

| Bill Nelson | 76 | Yes | D | 7 | 27 |

| Beto O'Rourke | 46 | No | D | 46 | 20 |

| Ted Cruz | 48 | Yes | R | 18 | 26 |

| Bob Menendez | 65 | Yes | D | 12 | 32 |

| Bob Hugin | 64 | No | R | 16 | 36 |

| Mick Rich | 65 | No | R | 11 | 27 |

| Martin Heinrich | 63 | Yes | D | 21 | 19 |

| Joe Manchin | 71 | Yes | D | 8 | 21 |

| Patrick Morrisey | 51 | No | R | 4 | 40 |

| Bob Casey | 59 | Yes | D | 13 | 22 |

| Lou Barletta | 63 | No | R | 9 | 26 |

| Sherrod Brown | 66 | Yes | D | 17 | 24 |

| Jim Renacci | 60 | No | R | 12 | 33 |

Sex

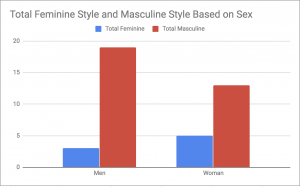

This research attempts to exhibit the difference between sex and gender in political science and gender communication research. There is a misconception that gender and sex mean the same thing, but gender is a style portrayed unrelated to the sex of a person. I found that within this sample 13.6% (3) of male candidates employed a Feminine Style of gender performance and 86.36% (19) of male candidates employed a Masculine Style of gender performance. 27.78% (5) of female candidates employed a higher Feminine Style of gender performance and 68.42% (13) of female candidates employed a higher Masculine Style of gender performance from the sample.

Figure 2. Feminine and Masculine Debate Styles

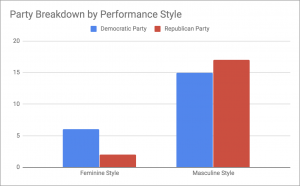

Party

In past gender and political science research that focused on sex and campaign content, party identification was the factor that was associated with most results. Unlike past research, I sought to differentiate sex and gender, and did not code for content, therefore I hypothesized that party identification should have no impact on the style of gender performance one would be categorized. Out of the 21 sampled Democrats, 28.57% performed in a Feminine Style and 71.4% performed in a Masculine Style. Out of the 19 Republicans sampled, 10.5% performed in a higher Feminine Style and 89.47% performed in a higher Masculine Style. Although there is not a significant numerical value to associate Democrats with higher feminine performance, it is important to note that more than double of the Democrats performed with a higher feminine style than the Republicans in this sample.

Figure 3. Party and Gender Debate Style

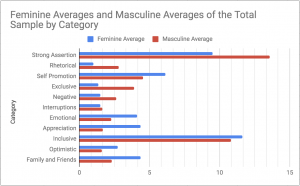

Coding Categorization Averages

Each statement category that was coded belongs to either a Masculine Style or Feminine Style of gender performance. The average numerical value each statement was employed by the candidates allows us to distinguish which categories were used the most and the least by each style of gender performance. Strong Assertions and Inclusive Statements were used the most by both Masculine Style or Feminine Style candidates. It is reasonable to assume that in a debate candidates will use both Strong Assertions to get a point across and Inclusive Statements when speaking to their constituents. The Feminine Style average is 9.5 and the Masculine Style average is 13.56 for Strong Assertions. The Feminine Style average is 11.62 and the Masculine Style average is 10.8 for Inclusive Statements. Strong Assertions is a Masculine Style code and Inclusive Statements is a Feminine Style code. Although both are close in value, the Masculine Style average for Strong Assertions is higher than the Feminine Style average and the Feminine Style average is higher than the Masculine Style average for Inclusive Statements. There is a trend among the data that each statement category average is higher within it’s scholarly based Feminine or Masculine classification, except for Self Promotion. Self Promotion is classified as a Masculine Style, but there is a higher Feminine average, 6.12 (feminine average) > 4.53 (masculine average).

Figure 4. Feminine and Masculine Debate Style

Self Promotion Paradox

The higher Self-Promotion results did not reflect the scholarly literature I researched to compiled the Feminine and Masculine Style Categories. I hypothesized that a third party factor could skew data from incumbency due to a possible higher track record to draw from when stating self-promotion. To test this theory, I found the total average of Self-Promotion of incumbents and non-incumbents. Incumbents have a higher average of (5.61) than non-incumbents (4.22).

| Incumbent | Non-Incumbent | |

|---|---|---|

| Count of Candidates | 18 | 22 |

| Total Average of Self Promotion | 5.61 | 4.22 |

While the averages of Self-Promotion of incumbents was promising, the count disparity between Feminine Style and Masculine Style incumbents was large. There are only 3 Feminine Style incumbents and 15 Masculine Style incumbents. The 3 Feminine Style candidates who are incumbents have a Self-Promotion average 6 and the 15 Masculine Style incumbents have a self-promotion average of 5.53. Both averages are very close in value. Not only is there an insufficient number of incumbent candidates coded as having a Feminine Style, but also the average of their self-promotion value does not hold a large difference to the average of the Masculine Style incumbent candidates.

| Masculine Style Incumbents | Feminine Style Incumbents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count . | 15 | 3 | ||

| Average Self- Promotion Style | 5.53 | 6 |

Therefore, I find an association between Feminine Style candidates and Self-Promotion to be equal to or higher than the association between Masculine Style candidates and Self-Promotion.

Discussion

Masculine Style Trend

By analyzing data that focused on the gender styles and debate types, gender styles and sex, and gender styles and party, there is a clear trend of the Masculine Style dominating each measure. Overall, the Masculine Style of gender performance is utilized significantly more than the Feminine Style of gender performance, despite the varied debate types. This trend in masculinity, within the realm of politics, is not unprecedented.

Within Jone’s research, the social identities and gender performance is accounted for within the context of politics. Jones describes gender as a performative act. For female politicians, being the minority, this performance is strategic and maintains “self-preservation” within politics. I found within my research the majority of women senatorial candidates performed with a higher Masculine Style. Jones explains how societal expectations shape the abilities to achieve goals. Within the sphere of politics, politicians have to perform to the public and their colleagues in order to be effective at their job. Jones referenced Margaret Thatcher as an example of a “linguistic makeover” and how women negotiate their authority among male colleges. The need for this arises because communication in government is biased toward the masculine style due to the assertions and strength to govern and persuade legislative bodies. (Jones 2016) Jone’s explanation of the political community of rewarding masculine styles of communications serves as a probable explanation for the high trend in the style of masculinity seem within my research of 2018 Midterm Senatorial debates.

Possible Explanation of the Self-Promotion Paradox

Based on scholarly literature, originally I hypothesized, prior to performing the content analysis, that the entirety of the five masculine style categories would have a total higher average held by the masculine style candidates. Similarly, I hypothesized that the 5 Feminine Style categories would have a higher total average held by the Feminine Styled candidates. I found these assumptions to be true, except in the case of Self-Promotion.

Self-Promotion is coded as a Masculine Style trait of performing gender. A possible third-party factor was incumbency. Incumbency has the possible ability to skew the data if a majority of the Feminine Styled candidates were incumbents running for reelection. This presented a possible third-party variable, because I speculated that incumbents may have more to speak on their prior term as senator, therefore can draw from a potentially larger pool of experience. When coding the candidates, typically I found that Self-Promotion came in the forms of references one’s past experiences and how they championed a bill through, worked across the aisle to accomplish something, or spoke on their accomplishments for their state. This form of promotion is expected within a political debate, but in order to confirm there was no incumbent variable skewing the data, I averaged the incumbent’s self-promotion score. The incumbent’s Self-Promotion average was higher than the non-incumbents, but there is an insufficient number of incumbent candidates coded as having a Feminine Style to be able to assume that incumbency had an impact on feminine style scores, therefore the association between feminine style candidates and Self-Promotion is not impacted by incumbency. By eliminating the third party factor, I speculate that within this particular context of political debates, Self-Promotion is a performance strategy used by all candidates regardless of their gender performance categorization. Debates function by discussing issues and articulating the differences between each party, therefore it is probable that the high use of self-promotion is reliant on the fact of the context being a debate, rather than the original scholarly literature.

Year of the Woman and Future Research

1992 was considered to be the “Year of the Woman” when 54 women were elected to the United States Congress. The 1992 record was broken in the midterms of 2018 when 117 women were elected to office (Salam 2018). Politics and the United State’s government is a male-dominated field, therefore political science holds meager amounts of research within this scale and size female participation compared to men.

Kathlene found the women are disadvantaged in committee hearings, because they are unable to participate equally as their male peers (Kathlene 1994). Jones found that Hillary Clinton’s linguistic style changed overtime with her campaign with her campaigns toward leadership, growing more masculine over time Jones 2016). Now with a growing body of female leadership and involvement from the 2018 Midterm Elections, it is important for political scientists to research the disadvantages women will face and the effects of this changing environment.

My findings suggest that everyone, including the 18 women sampled, an extensive majority of the candidates employed a masculine style of gender performance when debating. This research demands further research into a possible shift in the standard of gender performance. Additionally, if female candidates in any political position are disadvantaged by having to adjust to the norm of masculine styles of gender performance or if it is their original form of communication. There are so many unanswered questions about the impact of the 2018 Midterm Elections impact on gender communication in political science research. Likewise, there are many unanswered questions about gender performance within the 2018 Midterm Elections.

Conclusion

By performing a content analysis of the statements within the masculine and feminine style of gender performance from 20 2018 Midterm senatorial debates, I found that although my sample included different debate types, there was an overall trend of a Masculine Style of gender performance. The only outlier of this finding was that the feminine average of “self-promotion” statements was slightly higher than that of the masculine average. This outlier can possibly be explain by the nature of the content analysis, that being debates where participants are expected to speak on their abilities and achievements. The 2018 Year of the Women provides a varied sample of debates such as both women v men and women v women for senatorial seats. In a politically polarized and changing time in the United States government, the 2018 Year of the Woman follows the norm of performing a masculine style of gender within the senatorial debates.

Appendix A

Data Spreadsheet: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSgaitEcE5Z6jbriGlaq6qWQ3C69h_25ryIbgkgKl3FctdwvlIzjyMAUyMQa5FTlJ8s4u7ZBntQr-p7/pub?output=pdf

Midterm Senate Candidates Sample and Debates: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vTAdQTbMHTKjBGEFKToHUgkTroSuo87lBI9a1OiwRuXhN4DeM-N3zT_TUub1uRQJ5gINNofPp8a8MJb/pub?output=pdf

Appendix B

| Statement Category | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Strong Assertions | A belief or declaration using a strong tone | "This is our biggest issue!" "My opponents position is always higher taxes!" |

| Rhetorical | A statement asked or said to produce an effect and point to impress, persuade or used sarcastically | "You can't make this stuff up!" "Let's not fool ourselves" |

| Self Promotion | A statement promoting or publicizing ones achievements or better qualities | "That is why President Trump is endorsing me" |

| Exclusive | A statement using language that separates the individual from the the audience | " I will be the fighting voice in congress" "I will get us there" |

| Negativity | Statements expressing pessimism about the topic | "This state is in a terrible economic downfall that we need to fix" |

| Interruptions | An intrusion on someone's turn or statement | any interrupting noice or statement |

| Family/Friends | Any reference to the speaker's family or friends | "My son has a existing condition" |

| Optimism | Statements that express hopeful or positive outcomes | In our great state, we have a lot of work to do, but I am sure we will be able to get it done" |

| Inclusive | A statement using language that coneys the speaker part of the whole | "We" "Us" "Ours" "We should eradicate poverty in our cities" |

| Appreciation | Positive recognition of a topic or notion | "Thank you for your time on this Friday night" "I would like to nod to my counterparts across the isle" |

| Emotional | Any statement that uses a feeling word or describes an idea to illicit emotion from the audience | "I am heartbroken about what is happening at the boarder right now" |

References

Cameron, Deborah. Feminism and Linguistic Theory. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

Hart, Roderick & Jarvis, Sharon. 1997. “Political Debate: Forms, Styles, and Media.” American Behavioral Scientist 40 (8): 1095-1122.

Dow, Bonnie J., and Julia T. Wood. 2006. The SAGE Handbook of Gender and Communication. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Ifechelobi, Chiagozie, and Jane Nkechi Ifechelobi. 2017. “Gender Discrimination: An Analysis of the Language of Derogation.” IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science 22, no. 12: 23-27.

Jones, Jennifer. 2016. “Talk “Like a Man”: The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992–2013.” Perspectives on Politics 14 (3): 625-42.

Kathlene, Lyn. 1994. “Power and Influence in State Legislative Policymaking: The Interaction of Gender and Position in Committee Hearing Debates.” American Political Science Review 88 (3): 560-576.

Krolokke, Charlotte, and Anne Scott Sorensen. 2006. Gender and Communication Theory and Analyses. Sage Publishing, 2006.

Lawless, Jennifer L., and Danny Hayes. 2016. Women on the Run. Cambridge University Press.

Newman, Matthew & Groom & Handelman, & Pennebaker. 2008. “Gender Differences in Language Use: An Analysis of 14,000 Text Samples.” Discourse Processes 45: 211-236.

Salam, Maya. 2018. “A Record 117 Women Won Office, Reshaping America’s Leadership.” The New York Times. November 07 . Accessed May 09, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/07/us/elections/women-elected-midterm-elections.html.

Sanbonmatsu, Kira, and Kathleen Dolan. 2008. “Do Gender Stereotypes Transcend Party?” Political Research Quarterly 62, no. 3: 485-94. doi:10.1177/1065912908322416

Stubbs, Michael. 2001. “Words and Phrases: Corpus Studies of Lexical Semantics.” Blackwell. https://www.uni-trier.de/fileadmin/fb2/ANG/Linguistik/Stubbs/stubbs-2001-wordsphrases-ch-1.pdf.

Wilz, Kelly. 2016. “Bernie Bros and Woman Cards: Rhetorics of Sexism, Misogyny, and Constructed Masculinity in the 2016 Election.” Women’s Studies in Communication 39 (4): 357–60.

Wood, Julia T. 1997. Gendered Lives. 2nd ed. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Debate References

“Arizona Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452937-1/arizona-senate-debate.

“California Senate Debate.” C- Span.https://www.c-span.org/video/?453176-1/california-senate-debate

“Florida Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452442-1/florida-senate-debate

“Hawaii Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?453990-1/hawaii-senate-debate

“Wisconsin Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452562-1/wisconsin-senate-debate

“Nebraska Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?450392-1/nebraska-senate-debate

“Washington Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452555-1/washington-senate-debate

“Radio Campaign 2018 Minnesota Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?454171-1/radio-radio-campaign-2018-minnesota-senate-debate

“Massachusetts Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452950-1/massachusetts-senate-debate

“Michigan Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452899-1/michigan-senate-debate

“Mississippi US Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?454630-1/mississippi-us-senate-debate

” New Jersey Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?453283-1/jersey-senate-debate

“New Mexico Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452564-1/mexico-senate-debate

“Nevada Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452952-1/nevada-senate-debate

“North Dakota Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?453651-3/north-dakota-senate-debate

“Ohio Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?453650-1/pennsylvania-senate-debate

“Pennsylvania Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?453650-1/pennsylvania-senate-debate

“Tennessee Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452766-2/tennessee-senate-debate

“Texas Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?452966-1/texas-senate-debate

“West Virginia Senate Debate.” C- Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?453317-1/west-virginia-senate-debate