5 The Future of Divination

Juli Mindlin

Key Terms

- Divination

- Omens

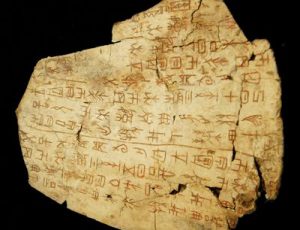

- Oracle Bones

- Feng Shui

Introduction

There’s power in prediction. The more you know about the world, the more people, or your citizens, will respect you. Even stemming back from early Chinese history, the Xia dynasty (2070 – 1600 BCE), stories were made up to help describe the land, its creatures, and their properties, like The Classic of Mountains and Seas or “The Tribute of Yu”. Moving beyond understanding the land and understanding the past, there were also many efforts to make the future and the spiritual more concrete. One way of doing this was through calendars, which would allow the government to stay on top of the weather and moon cycles. Another was through fortune telling and divination.

When I told my dad I was writing about divination, he said, “What, are you going to Hogwarts?”. It does seem fitting that this class is called “China’s Magical Creatures and Where To Find Them”, but that also made me realize that divination is a pretty foreign word to a lot of us, and people will often know it from fantasy worlds and not our own. Despite how foreign it may seem, it can be found in Judeo-Christian texts as well. In Deuteronomy 18, divination is counted as a sin, comparable to witchcraft, fortune-telling, and omen reading. In Genesis, the story of Joseph, he interpreted the dreams of prisoners to tell them about their future. This is to say that divination has been around for a long time, and not just in the East or in far-off fantasy worlds.

Before the start of the common era

Omens are markings of a distinctly good or bad event. In The Commentary of Zuo (chronicles from seventh to fourth century BCE), omens are explained to be caused by vital energy taking shape through distress or abnormality. If yin and yang are off-balance, even natural disasters can occur. While omens are passive, in that they can be quietly observed, divination is an active process of seeking out answers. Answers were often sought through reading tortoise shells and ox scapula in the Shang dynasty, and they were then written onto slips of bamboo. Oracle bones were available to the higher class and lower class, though diviners often used different resources dependent on class.[1]. Usually, heat was applied to the oracle bones until they visibly cracked. “Yes or No” questions were asked, and the direction of the crack would determine the answer. There have been many findings in which the original question has been inscribed onto the bone, some of which also show the answer, and if it wound up being a correct prediction or not.[2].

Divination as a skill lead to divination as an occupation. While divination by oracle bones was a method to be proficient in, there were also people who could read fortunes, outside of a popularized method. These people can be found in stories of the fangshi, along with magicians and doctors, who were comparable to diviners at the time. Many diviner-fangshi also used oracle bones, but many also had innate abilities to predict the future and were able to correctly predict their own deaths.[3]

During the Common Era

You might be wondering about more modern methods of fortune-telling, and maybe you’re thinking of Chinese fortune cookies. These secretive desserts actually have no involvement in Chinese history, though there are a couple of other interesting methods that do.

Like other methods of fortune telling, there are also masters of Physiognomy and feng shui. Physiognomy is the reading of a person’s face, features, and aura to predict their future. Feng shui is a method of luck determination based on the nature of a space, as opposed to the nature of a face. It uses knowledge from the Five Phases (wu xing) as a basis, and those who know feng shui can predict future events based on geography and directions, and can also help to change space accordingly.[4] Feng shui has been around since the Tang dynasty, and is still used today, even casually with interior decor. Planchette-writing, or fuji, also gained traction around the Tang dynasty, which involved written word from directly from spirits. Instead of a medium which a spirit speaks through, the medium is a translator of what the spirit creates by scratching a tray of sand with a stylus, this is comparable to the Ouija board.[5]

Conclusion

In some of these methods the future is concrete and non-interactive, and in others it can be questioned and possible changed. In concrete methods, just knowing the future can allow government to have social power and respect, like omens and fuji, and in more fluid methods, it allows people a sense of agency over their situations, like within oracle bones and feng shui.

Questions

- What other comparisons can you draw from divination and fortune telling to pop culture?

- What other comparisons can you make to the other content in this course?

Bibliography

Ji, Yun, and David E. Pollard. Real Life in China at the Height of Empire: Revealed by the Ghosts of Ji Xiaolan. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2014. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctt1pb626r.

Raphals, Lisa Ann. Divination and Prediction in Early China and Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511863233.

- Mu-chou Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare: A View of Ancient Chinese Religion, SUNY Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998), 27. ↵

- Lisa Ann Raphals, Divination and Prediction in Early China and Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 165-66, 183 ↵

- Raphals, Divination and Prediction in Early China and Ancient Greece, 132-146. ↵

- Yun Ji and David E. Pollard, Real Life in China at the Height of Empire: Revealed by the Ghosts of Ji Xiaolan, (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2014), 68-70. ↵

- Ji and Pollard, Real Life in China at the Height of Empire, 72ff. ↵