4 Calendars and their Power in Early China

Patrick Carmody

A Brief Introduction

Calendars. Everyone uses them, whether digital or paper; this seemingly rudimentary organizational item allows people to plan and track time, as well as events among many other things. What if these simplistic everyday items held so much importance they told you what to do? Not in the sense that you organized your time down to the minute and the calendar is your life, but the calendar decides how you live your life regardless of your wishes. Or what if a calendar influenced your thoughts on the president or your governor, how capable of governing they were? These thoughts seem far fetched and ridiculous in a modern lens. But this was very much the reality in early China, where calendars and the knowledge they provided reigned supreme not only over regular everyday people but also the emperor.

Key Terms

- Daybooks

- Oracle Bones

- Auspiciousness

Where to begin…

The first form of a calendar that appeared in China would have looked somewhat similar to what you see above, this is an oracle bone. I won’t go into too much detail on what an oracle bone is in this chapter, you can find more information on this in Inaya’s chapter, Divination in Early China. Oracle bones were pieces of bone, oftentimes coming from an ox, that had holes drilled in them and were cracked via a heating method. These cracks were observed and a spiritual outcome was determined from them. Additionally, sometimes records were written on the bones after their divination. These records were sometimes observations of astrological events, such as an eclipse or a planet passing, these records on oracle bones were a bare-bones version of a calendar.[1] These astrological events were the basis of the early Chinese calendar, which was a multilayered system of observations of the sun, moon, and planets,. It was mainly a lunar calendar, rather than what we use, a solar calendar.[2] Astrological events also held a larger meaning, a spiritual meaning, which influenced how calendars were used and how they affected life, from daily mundane tasks to the decisions the Emporer made, but more on that later.

Calendars and daily life

Calendars inadvertently or directly affect the lives of people today. They organize what you’re going to do and when you’re going to do it, but you still decide what days those events occur for the most part. A simple example is a wedding, the couple involved picks the perfect date that works for them and mark it on a calendar. But what if the calendar decided for you and you just had to go with it or face the inauspicious repercussions? This idea of the calendar deciding what you can and cannot do is the general concept of daybooks in early China.

Daybooks, known in China as rishu, looked something like the image above. They were made from bamboo strips held together by pieces of twine and then rolled up into something that resembled a scroll. This form of calendar was more often used by commoners than someone like the emporer.[3] The most analogous thing to daybooks in our modern society would be almanacs, although almanacs are not used as frequently as they once were. Daybooks resembled them when they were at their peak.[4] A major difference would be that daybooks went past the authority of almanacs, as almanacs served as a suggestion, a prediction of the seasons or events that determines what someone should do on a particular day, while daybooks determined what a person can do on a particular day, serving as “an established authority”.[5] This established authority came from the daybooks’ basis in spirits and religion. Daybooks apparently served as a religious text for the daily life of the commoner, because the religious teachings of Daoism at the time were difficult to directly translate to daily life.[6] If interested, you can find information on Daoism in Irene’s chapter “Daoism”.

To gain a general idea of what kind of restrictions a daybook may have had for certain days, we’ll rewind to the marriage example from before. The Daybooks were very specific, as they were for nearly every subject of life, on what days were suitable and not suitable to get married on; the day one got married on could affect the overall result of the marriage to the physical and social features of the wife.[7] For example, a repercussion of marrying on a wrong day could result in the “wife being talkative”, something deemed unfavorable at the time, or even more seriously the wife could “certainly die in childbirth”.[8] Daybooks affected more than just marriage, they influenced daily life as a whole, determining when it was acceptable or preferred to give birth, eat or drink, slaughter an animal, do construction or travel, and if these rules of practice weren’t followed major or minor disaster could follow as a result.[9] As previously stated, Daybooks were rooted in spiritual ideas, and these ideas determined what was and what was not acceptable on certain days, this auspiciousness affected not only commoners, but also the emporer and his court.

The Emporer and a Calendar

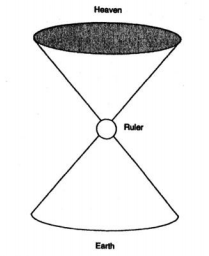

Emperors throughout the time of China’s dynastic era held a power called the Mandate of Heaven. This was essentially an order from heaven that concluded this emporer was seen as wise, powerful, and fit to rule by heaven, similar to European kings and queens being chosen by God. The Emperor was seen as a messenger from Heaven, a conduit that would be able to translate Heaven’s messages.[10] The main ways Heaven delivered messages to those on earth were through either astrological events like an eclipse or major events such as a flood or a fire. The Emperor, since he was partially from heaven, was supposed to be able to predict when these messages would be taking place, and what all of these messages meant, including what would come after them. The only way to do so without randomly guessing and hoping to get lucky, which would have made fool out of the emperor and could have resulted in a loss of respect and or power from those he ruled, was to have an accurate calendar to predict these events and make it seem like the emperor was being told what would happen by heaven. In this way, calendars exercised a large amount of power and influence in early China.

Additionally, the emperor was constricted by the auspiciousness of certain days just like the common people they ruled. In addition to the daily restrictions that commoners observed, the emperor has restrictions on when they could make major decisions, such as when to declare war, when to hold a battle, or when to go and raid a city.[11] If these restrictions weren’t followed the emperor could have faced a major loss not only on the battlefield but also in the spiritual realm, through the loss of the guidance of Heaven. At least that is what emperor’s court possibly would have thought.

Key Takeaways

- Auspiciousness influenced the daily decisions of those in early China

- An accurate calendar was power in early China

- Early Chinese calendars were created via viewing astrological events and were lunar based

- Calendars in early China did not look like our calendars of today

Bibliography

Liu, An, and John S Major. The Essential Huainanzi. Translations from the Asian Classics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Loewe, Michael. “The Almanacs (jih-shu) from Shui-hu-ti: A Preliminary Survey.” Asia Major, Third Series, 1, no. 2 (1988): 1-27.

Penprase, Bryan E. The Power of Stars : How Celestial Observations Have Shaped Civilization. New York: Springer, 2011.

Poo, Mu-chou. In Search of Personal Welfare: A View of Ancient Chinese Religion. Suny Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

- Bryan E. Penprase, The Power of Stars: How Celestial Observations Have Shaped Civilization (New York: Springer, 2011), 158. ↵

- Penprase, The Power of Stars, 159. ↵

- Mu-chou Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare: A View of Ancient Chinese Religion, SUNY Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998), 69-70 ↵

- Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare, 69. ↵

- Michael Loewe, “The Almanacs (Jih-Shu) from Shui-Hu-Ti: A Preliminary Survey,” Asia Major 1, no. 2 (1988): 15. ↵

- Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare, 69. ↵

- Loewe, “The Almanacs (Jih-Shu) from Shui-Hu-Ti,” 9; Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare, 71-72. ↵

- Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare, 72. ↵

- Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare, 74-75. ↵

- Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare, 76. ↵

- Poo, In Search of Personal Welfare, 76. ↵