19 The Ten Kings and Emperor Taizong

Jarrett Azar

The idea of Buddhist hell is foreign to many. Most people would assume a religion that is popularized on the idea of meditation and reaching nirvana would not have a concept of hell and suffering in the afterlife. A common view of the netherworld in early China, before the introduction of Buddhism, was the idea that after death one would go on a “netherworld adventure.” These stories shared the same basic structure, being that after a person dies, they have an adventure in the netherworld, then they revive, and their adventure is verified.[1] This view was very common in early medieval Chinese literature. Once Buddhism became popular in medieval China, the view of the afterlife considerably shifted. There are a few different interpretations of Buddhist hell. I will be focusing on the concepts that are depicted in eighteenth and nineteenth century Chinese hell scrolls.

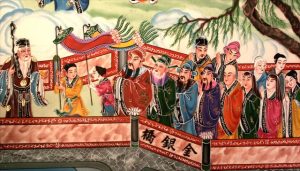

The idea of the Ten Kings actually does not detour too heavily from the netherworld adventure concept. Essentially, the Ten Kings serve as a trial system for the dead in the Buddhist afterlife. After one dies, they must pass each king after certain amounts of time and/or suffering. Each king will then decide whether they must continue or whether they can return to life as one of six life forms ranging from an insect all the way to a denizen of hell. This is similar to the idea of a netherworld adventure except for the fact that the revived person does not come back as themselves, even if they return as a human. This practice of depicting hell as a series of tests and kings dates back to the Tang dynasty. [2]

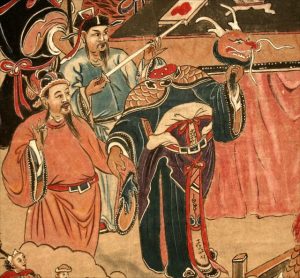

One of the more popular stories of afterlife pilgrimage is that of Emperor Taizong. In Journey to the West, the River Dragon asked Taizong to stop his execution by the Jade Emperor for not doing his job. Taizong agreed to help the River Dragon, but ultimately could not save him. Taizong then fell into a dream-like state where the River Dragon brought him to hell and made him face the courts of the ten kings for his failure to help the dragon. The emperor was quickly freed from hell, as he had not done anything wrong, but while there he saw many of the spectacles hell had to offer. These spectacles were common knowledge among medieval Buddhists and were turned into the hell scroll we will be focusing on in this chapter. [3]

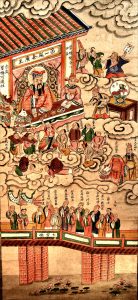

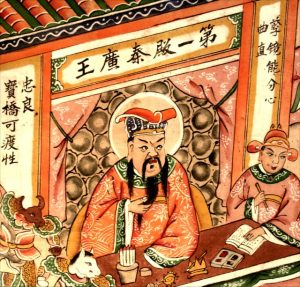

This hell scroll depicts the first court of hell, where the first of the ten kings resides. There are many interesting aspects to this hell scroll, which is the main scroll that I will focus on in this chapter. The first hell is depicted as a preliminary realm where one’s actions are reviewed and the subsequent tortures and/or rewards are assigned to them. One of the most important aspects of this court is the karma mirror. In this court of hell, one must stand in front of the karma mirror to see all of their misdeeds revealed and replayed before them. If you were the best person you could be in life, you could at this point leave the cycle of death and rebirth and join the Amitabha Buddha in paradise. Emperor Taizong’s story is so common that he himself became a common depiction in many hell scrolls. He is often seen standing next to the decapitated River Dragon. One of the more important aspects of both the depictions and the hell courts are the magistrates, or the ten kings. [4]

Each hell is overseen by a magistrate, their names and order generally consistent during the past millennium. Some of their names reflect older Indian traditions such as Yanluo or Yama of the fifth hell who was originally the First Ancestor dwelling in the abode of the dead and who gradually became regarded as a fearsome disseminator of justice in early India. Others are of Chinese origin, such as the king of Mount Tai, who oversaw the seventh hell. Tai Mountain is located in Shandong Province and associated with the dead at least since the Han dynasty. A final interesting aspect of the hell scroll is the “Bridge of the Seven Treasures.” This is the bridge that transports those who are leaving the cycle of death and rebirth to the “Western Heaven” or the “Pure Land”. The people who enter this land will never be reborn again, but this is the only escape from the traditional cycle. [5]

Overall, the idea of Buddhist hell is very interesting and is likely a new concept for many of the people who come across it. From the Ten Kings to Emperor Taizong, there is always something new to learn about the Buddhist concept of hell. For more background of some of these concepts, you can look at the previous sections of this chapter.

Citations

Brashier, Kenneth. “Taizong’s Hell.” https://people.reed.edu/~brashiek/scrolls.html.

Zhang, Zhenjun. Buddhism and Tales of the Supernatural in Early Medieval China: A Study of Liu Yiqing’s (403-444) Youming Lu. Sinica Leidensia. Leiden: Brill, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004277847.

- Zhenjun Zhang, Buddhism and Tales of the Supernatural in Early Medieval China: A Study of Liu Yiqing’s (403-444) Youming Lu, 1 online resource (VIII, 267 pages) vols., Sinica Leidensia (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 108. ↵

- Kenneth E. Brashier, “Taizong's Hell” (website), people.reed.edu/~brashiek/scrolls.html. ↵

- Brashier, “Taizong's Hell.” ↵

- Brashier, “Taizong's Hell: First Court – King Qin Guang”, https://people.reed.edu/~brashiek/scrolls/seriesA/01/index.html. ↵

- Brashier, “Taizong's Hell.” ↵