9 Taoist Exorcisms

Banishing Chaos Through Order

Jessica Orofino

Key terms

- Thunder rituals

- Exorcism

- Order

- Chaos

- Control

Overview

You are the ruler of a vast region in traditional China and your city is experiencing a severe drought, the crops are failing, and disease is spreading. It’s the demons again. Those lowly and unruly spirits occasionally wreak havoc on communities, causing drought, famine, disease, flooding, as well as panic and chaos. In addition to these general effects, demons and other lowly spirits can notice when living people are weak, or out of balance internally, and take advantage of their condition to make them ill or unlucky in other ways. Although generally considered weak beings, spirits can have great effects when unchecked or if they are feeling neglected by their descendants. The only problem is, if you cannot see the demons or perhaps speak their language, how can you make them stop wreaking havoc on your people? Traditional Taoist society had a structured approach to this through writing down legal notices to the governing celestial beings (deities) to remove destructive demons. In this section we will explore the relationship between demons, civilians, and exorcists in an attempt to show that exorcisms are about control and order within communities.

Exorcist Types

There are several subsets of exorcists, each having their own function in society, and upholding order due to their specific jobs. One type is a Taoist priest. Taoist priests are generally a more refined class of people, having gained authority through numerous texts, specific training, and having been endorsed and ordained by the government.[1] There is respect and authority conveyed by the elite social standing of this class of exorcists, something necessary to yield control over the spirit world.

Another class of exorcists during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) are the Fashi, who gain their authority through doing their duties well.[2] Fashi exorcists do not necessarily need to be highly educated or elite. In the name ‘Fashi’ itself, ‘Fa’ means a method or technique, a skill that needs to be mastered. Being a Fashi exorcist requires skill over anything else. Due to the variety of social statuses, Fashi can help in conjunction with either Taoist priests or spirit mediums.

Spirit Mediums are of the lower social standing for exorcists as a class of uneducated and unrefined people. These exorcists could be children, and their function was mostly to be the voice of spirits- a link between the spirit and Earthly worlds. In the Song Dynasty, spirit mediums were responsible for spirit-possessions and writing talismans (official notices) while in a trance.[3]

The distributions of power and control are spread equally among classes of exorcists, potentially helping to keep different social classes organized and able to be controlled since people of each class were able to contact the spirit world.

The Rituals

Exorcism rituals are themselves very orderly, a show of strength against the chaos demons can cause. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Taoist exorcisms were summarized as a calling out, identification, and defeat of an unruly spirit.[4] This is generally how the system was carried out in the Song Dynasty. As a subset of thunder rituals (rituals that are performed during thunderstorms), exorcisms dating back all the way to one of the earliest Taoist traditions in the 11th century (the Tianxin) began with the submission of a formal decree.[5] This submission required a person to go on a ‘meditational journey’, called visualization,[6] to the celestial (or spirit) world to present the correct deity with the command.

The command was brought on an official notice which was sometimes an amulet. This amulet could be inscribed either with the characters of an unrecognizable language or with representative pictures to convey the will of the people on Earth.[7] This would tell the deity what was needed to be done for the living people on earth. Even the writing of the amulets had their own set of rituals, prayers, and spells.

With such orders, the deity must then gather and command its spirit army to conquer the unruly spirit(s) in question.[8] Around the 11th century, “Shen-hsiao and Ch’ing-wei are two names of heavenly spheres where the divine patrons of the rituals in consideration reside and send down their subordinate Thunder generals with their spirit troops to execute in the world the ritual requests and orders that Taoist priests (tao-shih/fa-shih 道士/法師)4 had issued.”[9] Throughout the process of conducting a Taoist exorcism, there is a large emphasis on the order in which things are done and how they are done. Everything is made to be highly official, so as to maintain order and in turn build a great sense of power- the presentation of the correct amulet can cause a spirit army to be unleashed.

Depiction In Art

In Nanfeng, a city in China today, a ritual exorcism dance is performed to relieve houses and other buildings in the city of any unruly spirits that may bring disease or other misfortunes to residents.[10] Hundreds of troops of dancers make their way to potentially affected buildings and jump three times before entering. The dancers represent different aspects of an exorcism in warding off chaotic spirits- there are masked dancers who play the role of Dong Guai, a deity believed to drive away demons. This would be a deity that would be addressed by an earthly official like a Taoist priest through an amulet or other official notice, ordering the removal of demons. With many citizens and tourists filling the streets to watch the ritual, these dancers restore order by removing creators of chaos. A video of the beautiful event can be found here:

A scroll from the Song Dynasty depicts an exorcism in the mountains performed by the deity Erlang.[11] Viewing from right to left, as it would be in traditional China, an observer may first notice a well dressed man presenting a scroll to a gray, less well-kempt being (Zhong Kui). Zhong Kui is being presented an official notice to remove unruly spirits from the mountains from an exorcist. Zhong can be seen looking over towards the large, elaborately armored man. This is likely a representation of Erlang, a deity in charge of exorcisms, overseeing the exorcism and maintaining the highest authority. Later in the scroll figures that resemble Zhong Kui can be seen attacking an ox, women (possessed by fox spirits), a dragon, and more. The creatures being attacked are the ones who would not obey the commands of Zhong Kui to leave the mountain alone while the attackers are spirits who obey Zhong Kui’s command. Although the scene appears chaotic, it shows the order of command from exorcist to deity to spirits, as well as the process of diminishing chaos and disorder.

Desire For Exorcists

Rulers did often seek the help of exorcists to maintain order under their reign.[12] Part of the need for exorcists was to do a job ordinary people simply could not do. Things inexplicable by what could be seen are sometimes attributed the spirit world, something unseen that could not necessarily be ‘proven’ wrong. In addition, exorcists rituals show bystanders a visual means of believing that the spirit world exists and can interact with the exorcists. Belief in something that people can control is powerful. If rulers can control what happens to the citizens and society under their rule- or at least prevent the tamperings by unseen forces- they may be able to stay in power longer and have a more ‘successful’ rule. Due to the power behind having control over spirits, part of the duty of rulers and their officials was to do a year end exorcism.

Exorcisms and other thunder rituals were also used as a way for officials of the Song Dynasty to reaffirm normative cultural beliefs in opposition of local cults that did not follow normative ideas.[13] Officials would not question asking for the help of ritual masters (Shenxiao maters) and would even sometimes study under them. Exorcist abilities were a source of power to control the civilians, keeping them in their belief of familiar concepts that rulers were equipped to handle (as opposed to newer ideas coming around).

Summary

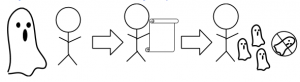

Ultimately, exorcists rituals themselves, how they are conducted, and who conducts them are all highly organized and structured. Each part of the ritual has a way that it is supposed to be done and a next step or being to report to. Rulers or other citizens request the help of an exorcist to remove an unruly spirit, exorcists create a formal request and give it to the correct deity, the deity commands other spirits to help conquer the chaos-causing spirits. Rulers use the rituals to show the people their ability to control what happens under their reign, and to provide their community an environment with as little chaos as can be due to spirits. In this way, it makes sense why these rituals are used to restore calm from the chaos of unruly demons.

How you can expand this chapter

- How Demons interact with the Earthly world and why

- How demons cause disease

- What exorcist rituals are like for the person affected by spirits

Bibliography

Davis, Edward L. Society and the Supernatural in Song China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001.

Andersen, Poul. “Tianxin zhengfa.” In The Encyclopedia of Taoism, edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. Routledge, 2007.

AvRuskin, T. L. “Neurophysiology and the Curative Possession Trance: The Chinese Case.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 2 (1988): 286-302. doi:10.1525/maq.1988.2.3.02a00070

Miller, Amy Lynn. “Otherworldly bureaucracy.” In The Encyclopedia of Taoism, edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. Routledge, 2007.

Katz, Paul R., and Paul R. KATZ. “Shenxiao.” In The Encyclopedia of Taoism, edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. Routledge, 2007.

max and., Beautiful China – Nanfeng Exorcism Dance – Jiangxi Province, accessed April 22, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WvIHWFBHFJg.

Reiter, Florian C. . “Taoist Thunder Magic (五雷法), Illustrated with the Example of the Divine Protector Chao Kung-Ming 趙公明,” Zeitschrift Der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 160, no. 1 (2010): 121–54.

Zheng Zhong. “Searching the Mountains for Demons (Soushan)” China, Late Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 22, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44630.

- Edward L. Davis, Society and the Supernatural in Song China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001), 46. ↵

- Edward L. Davis, Society and the Supernatural in Song China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001). ↵

- Poul Andersen, “Tianxin Zhengfa," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, edited by Fabrizio Pregadio (Routledge 2007). Accessed April 29, 2019, https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/routtaoism/tianxin_zhengfa/0. ↵

- Tara L. AvRuskin, “Neurophysiology and the Curative Possession Trance: The Chinese Case,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 2, no. 3 (1988): 286–302, https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1988.2.3.02a00070. 64. ↵

- Poul Andersen, “Tianxin Zhengfa." ↵

- Amy Lynn Miller, “Otherworldly Bureaucracy," The Encyclopedia of Taoism, edited by Fabrizio Pregadio (Routledge 2007). Accessed April 29, 2019, https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/routtaoism/otherworldly_bureaucracy/0. ↵

- Florian C. Reiter, “Taoist Thunder Magic (五雷法), Illustrated with the Example of the Divine Protector Chao Kung-Ming 趙公明,” Zeitschrift Der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 160, no. 1 (2010): 121–54. ↵

- Poul Andersen, “Tianxin Zhengfa." ↵

- Florian C. Reiter, “Taoist Thunder Magic (五雷法), Illustrated with the Example of the Divine Protector Chao Kung-Ming 趙公明,” 121–54. ↵

- max and., Beautiful China - Nanfeng Exorcism Dance - Jiangxi Province, accessed April 22, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WvIHWFBHFJg. ↵

- Zheng Zhong. "Searching the Mountains for Demons (Soushan)". China, Late Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 22, 2019, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44630. ↵

- Edward L. Davis, Society and the Supernatural in Song China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001), 46. ↵

- Paul R. Katz, “Shenxiao," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, edited by Fabrizio Pregadio (Routledge, 2007). accessed April 29, 2019, https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/routtaoism/shenxiao/0. ↵