10 Everyday Symbols Found in the Kitchen

Lauren Padko

Key terms

- Symbolization

- Culture

- Food

- Kitchen

Overview

Many old classical legends have been passed down from generation to generation in China, most of which have greatly influenced their manners and customs today. Since the earliest of ages, the Chinese have had a strong belief in supernatural or magical powers and some trust with charms and other objects that are protective against the spirits of evil. This chapter in particular will speak about how symbolism has been seen to gradually develop in China and specifically through the innocent objects seen every day primarily in the kitchen setting.

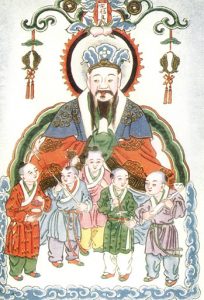

The God of the Kitchen, or the Stove God

Seen in some homes of China near the cooking stove, is a picture of the “Stove King” or sometimes referred to as the “Stove God”.[1] The worship of this god dates back to Wu Di, a devotee of Taoism, in 133 B.C.[2] The Stove King’s main responsibility is to allocate to each member of the family how long their life will be, bestow wealth or poverty, and he takes notes of the virtues of their home. He then reports this information to the Almighty God on the 23rd of the 12th moon of every year. On this specific day, it is customary to appease him with sweet meat offerings that are so sticky that when he reaches heaven he is unable to open his lips. Families will also offer up to him fruit, wine and sacrificial meats placed in front of his picture. Crackers are exploded to frighten off the evil spirits and once the ceremony is over, his picture is torn down and burnt and paper-money is given to the god and a toy horse which is given to carry him up to heaven. On the 30th of the month, the family pastes a new picture of the Stove King up and a sacrifice of vegetables is offered to him in order to secure his benevolence toward the home.[3]

The Importance of Food in Chinese Culture

Dating back at least 2,000 years, the symbolizations of different foods in China have come from superstitions and traditions all surrounding the same idea, to celebrate blessings. Food in China therefore has played an important role in the development of their culture, an example being all of the traditional festivals and events that are held each year with special foods. Some of these foods have particular meaning such as unity, commemoration, good luck and best wishes.

Making lists of specific numbers is another important aspect in Chinese tradition since some numbers are believed to be favored because they have positive meanings. This tradition intertwines with the symbolic meanings of food in their culture as well: ‘The basis for all food is water. There are five tastes, three substances, nine ways of boiling and nine ways of roasting, where it is a question of using the different kinds of fire. In mixing, one must correctly balance sweet, sour, bitter, spicy and salty; one must know which of these and how much is to be added first, which and how much later. The changes that take place in the food after it has been prepared and is still in the bowl, are so secret and so refined that there are no words to describe them. It is like the most subtle and artistic touches in archery and chariot-driving, or like the secret processes of natural growth’ (tr. Richard Wilhelm).[4]

The Symbolization of Popular Fruits

Apple

An apple is seen as an acceptable gift and can stand as a symbol of ‘peace’ or to the greeting, ‘Peace be with you’. Apple blossom is used occasionally for decorative purposes and is also seen as a symbol of feminine beauty. The wild apple typically blossoms in the spring time in Northern China and because of this, the apple can also be symbolized for the start of this season.[5]

Apricot

In the terraces of Northern China, there are an abundant amount of varieties of apricots grown.[6] An apricot is representative of the fair sex and its kernels are compared to the slanting eyes of a beautiful Chinese woman.[7] However, a red apricot is seen to represent a married woman who is having an affair with a lover. If the fruit is white, then it symbolizes the wish to have a hundred sons. An apricot is also seen as a symbol for March or the second month of the old Chinese calendar.[8]

Gourd

The watermelon is sometimes referred to as the ‘Western Gourd’ because of its importation from Western Asia.[9] There were many uses for gourds besides being an edible item for example, the boat people of Canton would tie the bottle-gourd to the backs of children to help them float if they fall overboard.[10] Gourd bottle figures were also created out of either wood or copper and would be worn as charms by older men to symbolize longevity.[11] In Central China, on the 7th day of the 7 month is the Feast of Women, and on this day, women make offerings of melons. In Canton, someone must never grant a melon as a gift because in Cantonese, the word, ‘xi’ in ‘xi-gua’, which means watermelon, is pronounced just like the word for ‘death’.[12]

Lichee

Lichee are grown in South China and can be seen around Europe and America as a dessert fruit. Together, water-chestnuts and lichee convey the idea of someone being ‘smart’. In Northern China, on a typical Chinese wedding night, lichees would be found lying under the marriage bed with the hope that the couple will be blessed with children soon.[13]

Mandarin Orange

Although the mandarin orange is particularly native to China and South-East Asia, it plays a significant symbolic role in Taiwan specifically. Here, it is a tradition to present mandarin oranges to wish a newly-wed couple a happy life together. This is done specifically by presenting a bride two mandarin oranges when she enters her future husband’s home which she then peels in the evening.[14]

Orange

An orange is seen to be a suitable gift for children or for the sick because of how expensive they were in Southern China. In ancient times, the Emperor would have oranges distributed to all of the officials on the second day of the New Year Feast as a symbol of good luck to all of his men.[15] On Chinese New Year, oranges would be given out to yearn for prosperity and happiness throughout the upcoming new year.[16] The bitter orange in particular, which is directly related to the common orange, symbolizes fate and destiny.[17]

Peach

Almost no other tree in China has so much symbolism attached to it as the peach tree does. The color of its wood has been said to keep demons away, its petals have the power to cast spells on men, and it is a symbol of immortality as well as the spring season.[18] The ‘peach-tree of the gods’ grew in the gardens of His Wang Mu and would only produce peaches once in three thousand years and would bestow eternal life to whomever ate them.[19] Peach boughs would be placed before the gates of houses and bows made of peach wood were made to drive the demons away at New Year’s.[20] The peach is the most usual symbol of longevity which in some ways connects to the popular deity, the Queen Mother of the West.[21] In the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), the Queen Mother of the West was seen in Shang oracle bone inscriptions as the quest for immortality increased.[22] To learn more about the Queen Mother of the West, go to Bianca’s chapter on Mt. Kunlun and the Queen Mother.

Pear

The pear is symbolic for longevity as it is known to produce fruit when it is 300 years old.[23] It is said that a happy couple should never cut up pears together since the word for pear is similar to the word for ‘separation’. Because of this, friends and families should also avoid dividing pears amongst each other. On the 15th day of the 7th month, no one should ever be given a pear since this is the day which the spirits of the dead spend on Earth. This could then bring misfortune and loss back to the homes of that particular family.[24]

Pomegranate

Since a pomegranate is filled with seeds, it is believed to symbolize fertility which can also be symbolized as children. Therefore, a popular wedding present is a picture of a pomegranate that is half open with the inscription, ‘liu kai baizi’, which means the pomegranate is open with a hundred seeds so there can be a hundred sons. Its symbolism of abundance and plentifulness makes it one of the ‘three fortunate fruits’ along with the peach and the finger lemon.[25] A pomegranate is also compared to a tumor which resembles a grinning mouth of teeth because of its intense red color and the abundant amount of seeds inside.[26]

A Few Miscellaneous Kitchen Items

Not only do specific foods have symbolic meanings, but so do the items that we use both to store and eat our food with.

Basket

Discovered in the Shang Dynasty, the eight immortals are a cluster of eight legendary immortals or xian whose powers can either present life or destroy evil.[27] Lan Cai-he, one of the eight immortals, is symbolized and praised by a decorated basket full of fruit or flowers. These items are presented specifically in a basket and are there to represent riches and good fortune from this immortal.[28]

A source to learn more about the eight immortals: Irons, Edward A. “Eight Immortals.” In Encyclopedia of World Religions: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, by Edward A. Irons. 2nd ed. Facts On File, 2016. https://muhlenberg.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/fofbuddhism/eight_immortals/0?institutionId=4200

Ceramic Bowl

The bowl represents the stomach of the Buddha, one of the eight Buddhist precious things. However, it can also represent that urn in which the bones of the dead are put into.[29] However, most ceramic bowls receive their symbolic meanings from all of the various decorative art that is painted onto them. This art is sometimes difficult to interpret since it is typically drawn from a certain person’s perspective and symbols can typically have many meanings associated with just one bowl. This particular perspective can even be determined through a specific time period such as Confucian, Buddhist, Daoist, etc.[30]

To learn more about how to read Chinese symbols in Art: “How to Read Symbols in Chinese art | Christie’s.” Chinese Ceramics: Decoding the Meaning of Traditional Symbols https://www.christies.com/features/Chinese-Ceramics-How-to-decode-the-meanings-of-traditional-symbols-7229-1.aspx.

Chopsticks

Going back to at least 1,200 B.C, chopsticks were first found in individual’s coffins. In order to not bring bad luck, they should not be lent to anyone because they can break very easily and they should never be left inside the bowl or on top of a plate. In the Book of Rites, it is stated that chopsticks should never be used for eating rice or millet. However, this book was mainly concerned with ceremonial occasions and eating habits directly related to the upper-class members which can be one reason for this disallowance since it was seen to be improper behavior.[31]

Summary

Although this is only a small insight into the hundreds of symbols that pertain to the Chinese culture, there will always remain running themes throughout the symbolic meanings. Most of these symbols stem from the things that pertained the most to the Chinese in their everyday lives such as to attain a high social rank, the after-life and the belief of rebirth, immortality, and avoiding sin.[32] This chapter in particular focused on the most popular fruits, items and divine figures focused on in the Chinese culture and how symbolizations can have different symbolic meanings depending on the time period.

How you can expand this chapter?

- Discuss various Feast Days and Holidays celebrated

- Include more fruits or other foods that have significant symbolic meanings

- Expand on the symbolic meanings of art

- Include how Feng Shui pertains to this specific topic

Bibliography

Carter, Martha L. “China and the Mysterious Occident: The Queen Mother of the West and Nanā.” Rivista Degli Studi Orientali 79, no. 1-4 (2006).

Christies. “How to Read Symbols in Chinese art | Christie’s.” Chinese Ceramics: Decoding the Meaning of Traditional Symbols | Christie’s. April 13, 2016. https://www.christies.com/features/Chinese-Ceramics-How-to-decode-the-meanings-of-traditional-symbols-7229-1.aspx.

Cohen, Myron. “The Kitchen God & Other Gods of the Earthly Domain.” Columbia University: 2007. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos/prb/earthly.htm

Eberhard, Wolfram. A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. New York, NY: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1986.

“Eight Immortals.” Wikipedia. March 22, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eight_Immortals.

Hung, Wu. “Xiwangmu, the Queen Mother of the West. https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/wuhung/files/2012/12/Xiwangmu-the-Queen-of-the-West.pdf

Irons, Edward A. “Eight Immortals.” In Encyclopedia of World Religions: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, by Edward A. Irons. 2nd ed. Facts On File, 2016. https://muhlenberg.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/fofbuddhism/eight_immortals/0?institutionId=4200

Nilsson, Jan-Erik. “Symbolism.” GLOSSARY: Symbolism. Gothenburg, Sweden. June 27, 1999. http://gotheborg.com/glossary/symbolism.shtml.

Williams, C.A.S. Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art Motives. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc, 1976.

- Myron Cohen, The Kitchen God & Other Gods of the Earthly Domain (Columbia University Press, 2007), 1. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos/prb/earthly.htm ↵

- C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art Motives (New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc, 1976), 210. ↵

- Ibid, 211. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought (New York, NY: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1986), 113. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 21. ↵

- C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art Motives, 18. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 21. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 132. ↵

- C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art Motives, 217. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 133. ↵

- Ibid., 163. ↵

- Ibid., 178. ↵

- Ibid., 219. ↵

- C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art, 301. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 219. ↵

- Ibid., 228. ↵

- C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art, 316. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 228. ↵

- Martha L. Carter, “China and the Mysterious Occident: The Queen Mother of the West and Nanā.” Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, 102. ↵

- Wu Hung. Xiwangmu, the Queen Mother of the West, 24, https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/wuhung/files/2012/12/Xiwangmu-the-Queen-of-the-West.pdf ↵

- C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art, 319. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 229. ↵

- Ibid., 240. ↵

- C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art, 333. ↵

- "Eight Immortals." Wikipedia. March 22, 2019. Accessed May 04, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eight_Immortals ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 31. ↵

- Ibid., 47. ↵

- Nilsson, Jan-Erik. "Symbolism." GLOSSARY: Symbolism. (Gothenburg, Sweden, June 27, 1999), 1. ↵

- Wolfram Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols – Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought, 63. ↵

- Ibid., 13. ↵