16 The Significance of Tomb Burial

Regina Lau

Key Terms

- Coffin (guan 棺)

- Filial piety

- Biography of Chen Fan 陈蕃

- Above ground/ underground

- hun/ po spirits

- “Spirit Seat”

- li (禮)

Introduction

What comes to mind when you hear the words afterlife, or burial, or tomb? Do you think the dead will have a second life when they are dead? Often, people do not think of providing offerings for the dead. Not the Chinese, because they value providing offerings to the dead; they consider it beneficial, and they practice filial piety. There are different layers that we need to understand to learn more about the ideas of the afterlife in China, in particular about the burial in a tomb. We will go back in time to the dynasties of early Chinese history to figure out the true meaning.

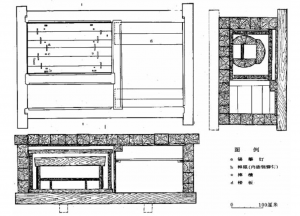

Separation of the dead and living

An (inner) coffin (guan 棺) and outer coffin (guo 槨) are the essentials for the dead[1]. It is important because of their structure, design, and the object itself too. Since burial is most common in China today, there must be a reason for this ritual. A coffin is a container that can separate and hide the body from a human eye. It is symbolic because the object can “seal” and “lock” the spirits of the hun and po, the two aspects of the soul. Once the coffin and the guo are sealed, it would not be opened again, so that hun and po would not come out. This is the first reason for using tomb burial, but there are also other concepts that contribute to this choice.[2]

Fear of death

There is a “myth” of fearing the dead: the fear that the dead will come back to haunt and give bad luck to others. Chinese people believed that this idea could not be challenged. The fear has been fully immersed into other’s minds that there is power involved. Power can be determined by how powerful the dead can be. That power has influenced the living to provide offerings as a sign of respect and also as the need to do it. The idea behind the word “fear” can describe the culture of tomb burial. It is because when a coffin is locked away it also locks the spirits metaphorically and physically, it can make others pray for the dead. We must understand that there are other ways to treat a dead body, but the Chinese preferred it this way and this can indicates the significance of tomb burial.

The bureaucracy of the afterlife

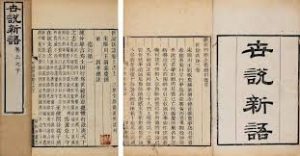

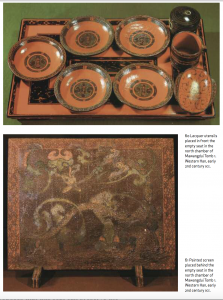

The living and the dead have two different but similar bureaucracies. The afterlife has much more power than most people would think. The afterlife has its own set of rules, position, and status that the dead have to follow. People provide offerings to make the dead happy and content because they do not want the dead to come and haunt them with ghosts and bad luck. With this idea, there is a force for providing offerings to the dead, like providing utensils and goods inside the coffin. There are also other ways to offer to the dead. People can change offering methods, for instance instead of putting goods inside the tomb, they can burn materials like incense, and paper money, or paper models of houses, etc., but the practice of burning goods did not start until well after the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). During the Han, there was a tradition that people who had a criminal record were not allowed to attend to provide offerings. [3]. If you want more information about offerings for the dead, read one of the classics of Chinese history, the Book of Rites (Li ji 禮記).[4]

Filial piety

Why would people be determined to go so far out of their way to create or pay for extravagant funerals? Why would they interact with the dead despite their fear of death? The answer comes down to filial piety, a concept that was developed by Confucius. [5] Filial piety is the “motivating” factor of tomb burial because it represents “people’s performance of proper ritual li (禮)”[6]. The main reason for this practice was to put the society in order and peace but it was never imagined that it would have a huge influence in this ritual. During the Pre-Han period and followed by many dynasties after, it has developed a culture to serve people according to the standards of li (ritual propriety). An example would be the Han dynasty’s strong emphasis on filial piety: officials were selected for government service if they showed filial obedience. This caused funerals to be extravagant during the Han period.[7].

Earlier stories during the Han include that of Zhao Xuan 赵宣 in the “Account of Chen Fan 陈蕃” (Chen was the governor in Zhao’s area). Zhao lived in the tomb-in chamber with his parents for twenty years, and that showed “exceptional filial piety”[8]. Filial piety has been a long living concept that continues to influence others, even today. In fact, Wu Hung argues that no other ancient civilizations in the world would devote similar time and effort for concealment of the dead.[9]

To be Continued

Just like historians and archaeologists continue to discover new findings, this topic also needs to be researched further. According to Wu Hung, the director and professor of Chinese history at the University of Chicago, he thought about how the theory of “the spirit seat stood for the invisible soul of the tomb occupant”[10]. This proposes that this seat is meant to preserve the soul of the dead but unfortunately his theory has not been proven yet. As this topic continues to be researched, ideas in this textbook may not paint a whole picture but further research can evolve our understanding of this topic.

Bibliography

Hung, Wu. The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs. 1 online resource (274 pages) vols. London: Reaktion Books, 2011.

Poo, Mu-Chou. “Ideas Concerning Death and Burial in Pre-Han and Han China.” Asia Major 3, no. 2 (1990): 25–62.

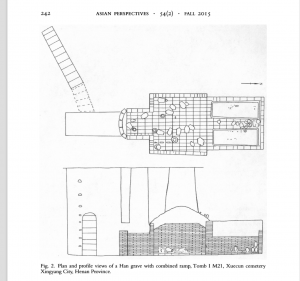

Ligang, Zhou. “Obscuring the Line between the Living and the Dead: Mortuary Activities inside the Grave Chambers of the Eastern Han Dynasty, China.” Asian Perspectives 54, no. 2 (2015): 238–52.

- Wu Hung, The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs., 1 online resource (274 pages) vols. (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 20. ↵

- Hung, The Art of the Yellow Springs, 22. ↵

- Zhou Ligang, “Obscuring the Line between the Living and the Dead: Mortuary Activities inside the Grave Chambers of the Eastern Han Dynasty, China,” Asian Perspectives 54, no. 2 (2015): 244 ↵

- See for instance chapters XIII, XVIII and XIX in this translation: Book of Rites ↵

- Ligang Zhou, “Obscuring the Line between the Living and the Dead," 239 ↵

- Mu-chou Poo, “Ideas Concerning Death and Burial in Pre-Han and Han China,” Asia Major 3, no. 2 (1990): 26 ↵

- Ligang Zhou, “Obscuring the Line between the Living and the Dead," 238. ↵

- Ligang, Zhou, “Obscuring the Line between the Living and the Dead," 245. ↵

- Hung, The Art of the Yellow Springs, 10. ↵

- Wu Hung, The Art of the Yellow Springs, 65-67. ↵