8 Daoism

Irene Keeney

Key terms

- Daoism/Taoism

- Dao/Tao

- Daodejing [Tao-te-ching]

- Laozi [Lao-tzu]

Introduction

Spirituality in China has always been important, from oracle bones used by Shang kings, to the offerings to ghosts even nowadays, to the five phases permeating history. These spiritual practices have been ingrained in the culture for thousands of years. However, they were never really associated with a religion.

Not many people have learned about Daoism (Taoism). It is an ancient religion based on the teachings of Philosopher Laozi (±500 BCE). This makes Daoism a particularly difficult religion to understand because it is made up of two parts: Religious Daoism and Philosophical Daoism. In this chapter, I hope to go deeper into what Daoism is and how it has deeply affected Chinese culture. I hope to provide a good explanation to a vastly complex religion with many intricate yet important parts.

Introduction to Daoism

Daoism can be divided into four time periods: classical Daoism (fifth century BCE–second century BCE), early-organized Daoism (first century CE–seventh century CE), later organized Daoism (seventh century CE–early twentieth century CE), and modern Daoism (1911 CE-Present). While is has been called Daoism through this time, it has changed immensely. Some people even consider it more of a philosophy or way of life rather than a religion.[1]

Daodejing

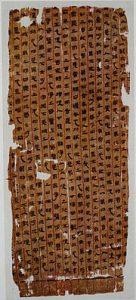

The Daodejing (Classic of the Way and the Power) is the first and, arguably, most important text in Daoism. It has exactly eighty-one chapters is divided into two roughy equal parts. The first part describes Dao, and the second part describing De. It essentially maps everything a practitioner of Daoism needs in order to live a successful life. The Daodejing could be described as “more as a collection of sayings than a philosophical discourse.”[2]. It has several sayings that people are still aware of today, although they might not know the origin.

True words are not beautiful; Beautiful words are not true. A good man does not argue; He who argues is not a good man. The wise do not have extensive knowledge; Those of knowledge tend not to be wise. The sage does not collect things for himself, Yet the more the does for others, the more he gains, The more he gives to other, the more he possesses.Just as the way of Heaven is to benefit all and not do harm, So the way of the Sage is to act but not compete. (Daodejing, Ch. 81)[3]

In 1973, a tomb was excavated in Mawangdui, near Changsha (Hunan province), containing a man, a woman, and her son dating back to the Han dynasty. Along with the bodies, it contained several treasures, including two copies of the Daodejing, meaning that the text was so important, people were buried with it. These are called the Mawangdui version of the Daodejing, and is different from other versions of the text we have.

The Legend of Laozi

Laozi is thought to be the author of the Daodejing. He is a mythical/historical figure placed in the sixth century BCE. Some believe that Laozi was Confucius’s teacher. He was a sage and is given the credit for a book of ancient sayings, known as The Analects (Lunyu), written during the Warring States period (476–221BCE).

Laozi was apparently an official during the Zhou Dynasty, but when it seemed like the dynasty would fail, he left China in order to travel the lands of the west. According to tradition, his personal name was actually Li Dan. Laozi’s decedents would supposedly continue to advise emperor’s to come. Eventually, as centuries passed, Laozi became a Daoist god known as The Highest Lord Lao (Taishang Laojun).

The Dao and the De

The first part of the Daodejing explains what is known as the Dao. Understanding the Dao is one of the major parts of Daoism. Livia Kohn says the Dao is “… underlying cosmic power which creates the universe, supports the culture and the state, saves the good, and punishes the wicked.”[5] The Dao as a concept is very difficult to understand. However, there is an aspect of Dao called the “Dao that can be spoken” that people can understand. In Daoism, when one fully understands what is known as the “Eternal Dao”, they cannot tell others what it means –because it cannot be expressed with words.

Those who know don’t talk. Those who talk don’t know. Close your mouth, block off your senses, blunt your sharpness, untie your knots, soften your glare, settle your dust. This is the primal identity. Be like the Tao. It can’t be approached or withdrawn from, benefited or harmed, honored or brought into disgrace. It gives itself up continually. That is why it endures.” (Daodejing, Ch. 56.)[6]

Thus, Dao can be thought of in two different categories, “The Dao that can be spoken” and “the Eternal Dao”. The Eternal Dao is what is in the universe that is intangible. These are things ranging from emotions to spirits to the gods that control or create the world. The Eternal Dao is what humans try their whole lives to fully understand. The Dao that can be spoken refers to the tangible things in life such as nature. These are the things that we can easily understand because we see and experience them so frequently. Both Dao are important to out lives and both are essential in living a full life, according to the Daodejing.

Another important concept brought up in the Daodejing is the De. De is called “the Dao within”, otherwise known as virtue. De is how someone lives their lives.

Bibliography

Kohn, Livia. Introducing Daoism. University Park, PA: [Journal of Buddhist Ethics], 2009.

Mitchell, Stephen. Tao Te Ching. Harper Perennial, 2014.

Additional resources

Campbell, Trenton. Gods & Goddesses of Ancient China. Gods and Goddesses of Mythology. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, 2015.

Kohn, Livia. The Taoist Experience: An Anthology. SUNY Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1993

Tang, Yijie. Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, Christianity and Chinese Culture. China Academic Library. Heidelberg: Springer, 2015.

- Kristin Johnston Largen, Finding God among Our Neighbors: An Interfaith Systematic Theology. Volume 2, (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2017), 91. ↵

- Livia Kohn, Introducing Daoism (University Park, PA: [Journal of Buddhist Ethics], 2009), 17. ↵

- Kohn, Introducing Daoism, 17. ↵

- Kohn, Introducing Daoism, 18. ↵

- Kohn, Introducing Daoism, 20. ↵

- Stephen Mitchell, Tao Te Ching, (Harper Perennial, 2014). ↵