24 Daiji the Fox Spirit

Kaitlyn Jannuzzi

Key Terms

- Su Daji

- King Zhou of Shang

- Fengshen yanyi (Investiture of the Gods/ Creation of the Gods)

Background

The story of Daji from the Investiture of the Gods (Fengshi yanyi) isn’t historically accurate; it’s better classified as Ming dynasty fan fiction. The story wasn’t the first account of the fall of the Shang dynasty. The Story of King Wu’s Campaign Against Zhou is more realistic and was written during the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368). The author of Investiture of the Gods, Xu Zhonglin, wrote his version during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) likely based on this text and some other less popular publications. He used his vast knowledge of celestial beings to explain that the gods had a major part of the fall of Shang with Daji, an evil 1000-year-old fox spirit, smack dab in the middle of it all.[1]

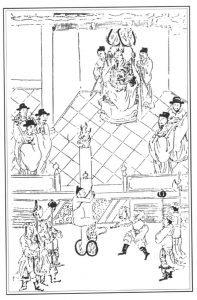

Investiture of the Gods

Investiture of the Gods (Fengshi yanyi) takes place at the end of the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) under the rule of King Zhou.[2] This story describes the godly interventions that take place throughout the final years of the Shang dynasty (The Trojan War is a good comparison). The first chapter explains that King Zhou went to the temple of Nüwa, the snake goddess, to pay his respects. When he saw the statue of the beautiful goddess he instantly became infatuated with her and carved an explicit poem into one of the temple’s pillars which offended the goddess. King Zhou would have died for this but Heaven decreed he still had twenty-eight years to his life. Nüwa decided to send a thousand-year-old fox spirit to distract King Zhou from state affairs, thinking his life might end faster if he lost the support of the state officials and Heaven. So, the fox spirit entered the palace under the guise of Su Daji, a minister’s daughter who was set to be gifted to King Zhou. Shang descended into disarray when Daji enters the palace and, as per Nüwa’s orders, and the king stops attending meetings and spends all of his time with Daji. Aside from distracting King Zhou, Daji helped the king develop new forms of torture and convinced him to kill many of his loyal ministers and subjects. Daji is killed in chapter 97 after she was captured by Nüwa and killed by rebels, King Zhou repented his mistakes and kills himself by lighting his palace on fire in the same chapter.

Famous Forms of Torture Invented by Daji

- Wine Pool:

- Maids and eunuchs were paired up and made to drink from the pool until they were drunk, and then made to perform tricks. This was done to amuse Daji.

- Meat Forest:

- The drunken pairs from the wine pool were sent to a forest of meat. One of Daji’s favorite activities here was to watch the pairs be stripped naked and play games like tag or hide-and-seek. At night, Daji would enter the meat forest to eat the dead bodies.

- Snake Pit:

- A deep pit filled with snakes. Victims were thrown into the pit and were quickly eaten alive by the snakes. This was mostly used to kill minsters who offended King Zhou.

- Brass Pillar:

- A hollow brass pillar was filled with hot coals. Victims were stripped naked and tied to the burning pillar, it is said they turned to ash instantly. This was also used to kill minsters who offended King Zhou.

The Tragedy of Queen Jiang

Queen Jiang, King Zhou’s first wife, was an early victim of King Zhou and Daji’s rage in a very unique way. The queen had seen how Daji was negatively affecting the king’s attention to state affairs so she treated Daji with little respect. Since Daji was only a concubine, she had to show respect to Queen Jiang, despite the queen embarrassing her in front of all the other concubines. Not being able to take the humiliation, Daji concocted a plan to dispose of the queen. She arranged for someone to ‘attack’ the king as he finally went to court and say he was sent by the queen after he was very easily captured. The king was livid that the queen had tried to kill him but Shang law said that he could not torture or kill his first wife even if she had committed a capital offense. Daji didn’t care much for this law and suggested that if the queen didn’t admit to sending the assassin, to gouge out one of her eyes since she would most likely prefer to keep her eye than continue to plead innocent. Unfortunately for Daji, the queen continued to plead innocent even after having lost an eye and even gave a very compelling argument that almost convinced the king to let her go. Daji wouldn’t let that happen and said the argument the queen gave was a lie to trick the king and if she continued to plead innocent then they should burn off her hands. The king agreed and the queen tragically died after her hands were burned off in boiling oil. This anecdote fueled the plot as it resulted in Queen Jiang’s two sons leaving Shang to look for help to overthrow their tyrant father at the end of the story. It also shows just how much influence Daji had over the king, by showing how little effort it took to make King Zhou completely disregard a law that may have gone back to the creation of the Shang Dynasty or further.

Why is Daji the guilty one?

Daji isn’t innocent by any means: she was the reason many people died, which –according to the novel– could be in the hundreds of thousands if you count the king ignoring flood and famine as her fault. However, she never actually broke her promise to Nüwa to not kill anyone. Daji only persuaded King Zhou to kill people on her behalf. She also didn’t do anything to change King Zhou’s behavior, he had already lost interest in government before Daji entered the story. King Zhou was known to have an obsession with women and wine and a short temper that easily led to violent outbursts. Although King Zhou was a horrible tyrant, he is somewhat redeemed at the end of the story by recognizing his errors and killing himself while Daji was beheaded not too far outside his palace. The rebels in the story didn’t forgive King Zhou, but Daji is known as one of the primary reasons for the fall of the Shang dynasty. To me, this seems unfair because Daji was only carrying out the orders of Nüwa while King Zhou had no purpose in being as cruel as he was other than self-indulgence.

From a modern perspective, Investiture of the Gods isn’t just a piece of historical fiction that depicts the fall of a dynasty. It is evidence of the tragic trend of how poorly women are often depicted in tales of old. Despite King Zhou being corrupt and dismissive of his duties before Daji’s arrival, everyone in the story blamed the tyrant’s behavior on her. Even the author allowed her to take the fall for everything, and allowing King Zhou to redeem himself by realizing his wrongdoings and ending his life. Meanwhile, Daji was beheaded when Nüwa, the very deity who sent her to wreak havoc on the Shang dynasty in the first place when she couldn’t kill King Zhou herself, left her for dead and preserved her own image as a benevolent goddess. Calling the fox spirit by the name of Daji is also using a woman as a scapegoat. The rebels against king Zhou never found out that the real Su Daji had died and blamed it on an innocent girl. Because of this, as we read this story and many others we need to keep in the mind the views people at the time of writing held on certain people and groups, and use that insight to best analyze the text.

Food for thought

Based on the chapter on Fox Spirits, we know thousand-year-old foxes can choose to take the form of a man or a woman. Daji chose to do neither as she possesses the dead body of Su Daji.

How many the story have changed if:

- Daji had become King Zhou’s concubine using her own female form?

- Daji had somehow completed her task using a male form (ex. entering the palace as a minister)

Bibliography

Wan, Pin Pin. “‘Investiture of the Gods’ (Fengshen yanyi): Sources, Narrative Structure, and Mythical Significance.” , Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington, 1987. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0362502800002820.

Xi, Zhonglin. Creation of the Gods. Translated by Zhizhong Gu. Beijing: New world Press, 1996.