2 Chinese Creation Myths

Hunter Sobel

Key terms

- Pangu

- Hundun

- Cultural Exchange

- Minority Groups

- Oral Tradition

Chinese Creation Myths

As a vast and culturally diverse land with a long history, China has produced a great variety of myths and cosmologies. Though often misunderstood, the creation myths of China are equally diverse. Over time many creation myths have changed or lost relevance entirely reflecting various changes in Chinese culture. The myths themselves exist within an interconnected web of spiritual and philosophical concepts such as Yin and Yang. This chapter contains an overview of both popular Han creation myths and the myths of minority communities and aims to supply insight into how they fit into different Chinese cosmologies.

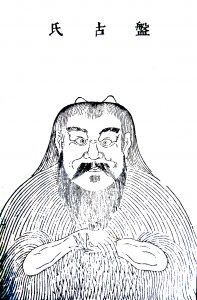

Pangu and Chaos

The story of Pangu is possibly the most well known of the Chinese creation myths. The earliest known records were produced by Xu Zheng in the Three Kingdoms period (222 CE – 263), although it is unknown when the myth was first developed. There are two main manifestations of the Pangu myth which have developed throughout Chinese history.[1] The first version states that in the beginning heaven and earth were one in a chaotic egg form known as the Hundun. Pangu, meaning “coiled-up antiquity”, was born inside this egg and after 8,000 years split it in two, creating the separation of heaven and earth that we humans are now familiar with. During this process Pangu grew 10 feet every day while heaven increased 10 feet in height and the earth 10 feet in thickness daily. Pangu is considered to have separated the earth and heavens by 90,000 li (almost 28,000 miles), where they remain till this day.[2] This division of the world into two opposing domains strongly relates to the cultural focus in Daoism on dualities, manifested in the form of the Yin and Yang. In this cosmology the creation of binaries coincides with the creation of the universe.

In the second main form of the Pangu myth, Pangu is referred to as the “firstborn.” However, the birth of the world begins upon his death, wherein his body is transformed into the world as we know it. Pangu’s breath became the wind, his eyes the sun and moon, his blood the rivers, etc. It is written that parasites on his body, impregnated by the wind, would become humans.[3] In a way this also touches on Daoist dualities in that from death comes life, implying that both concepts are interdependent. Overall, the first myth has been more dominant throughout Chinese history.[4]

The earliest accounts of Pangu may have been in the Three Kingdoms period, though records of similar myths date back even further. The Zhuangzi, produced between 350 and 222 BCE., describes a similar myth from which the myth of Pangu could have potentially been derived. In this myth, the chaotic force in the Pangu myth, referred to as Hundun, takes the form of a generous emperor of the central region of China. Hundun is described as having no holes, evoking the sac-like egg of the Pangu myth. The emperors of both the North and South seas, who often visited Hundun, believed that all men should have seven holes and began to bore one hole in Hundun daily which ultimately caused his death on the seventh day.[5] This myth clearly contains elements of the previous two, but there is something even more interesting about this myth in regards to its element of social commentary. In Chinese culture the sac is a symbol of what is natural. The emperors bore holes in Hundun based on a belief that his natural state is in some way wrong, which is a reference to the Confucianists’ creation of modern civilization.[6] In a sense the story is stating that the institution of Confucian values led to the death of man in his natural state.

A text of possibly even earlier origin, the Laozi, describes an origin story focused around a similar chaotic force except in this case without a creator deity entirely. This force is referred to as “the Way” and is described as vast, formless, and complete. The tale claims that humans modeled themselves after the earth, the earth modeled itself after heaven, and heaven modeled itself after “the Way”, which is eternal and does not need to model itself on anything.[7] The lack of a real creator deity in some of these early myths led the scholarly community to erroneously conclude that China lacked a creation myth entirely. Some scholars also concluded that the myth of Pangu was borrowed from India, due to similar myths existing in the area, enforcing the concept that the idea of a creation myth was alien to China and something it adopted from influence of foreign lands.[8] Historian Paul Goldin believes that scholars were deluded by the perception that China represented a culture totally alien and opposite from the Western world which led to the spread of these ideas.[9] However more recent discoveries have led to a new understanding of the world of Chinese creation myths.

Creation Myths within Minority Communities

Western scholars have historically failed to properly document the creation myths of China. The majority of scholarship has focused only on the stories of Pangu or Nuwa and Fuxi, though in reality China has had countless undocumented creation myths that have been translated orally within Chinese minority communities.[10] However, since the 1990s these storytelling practices have been receiving far more attention.[11] These myths are so numerous and diverse, in fact, that scholar Wang Xianzhao has developed three sets of criteria in which to categorize any given myth:[12]

Category 1: Types of Creators

- Creation Without a Creation

- Creation by Gods

- Creation by Religious Figures

- Creation by Cultural Heroes or Divine Figures

- Creation by Ancestors

- Creation by Common People

- Creation by Animals

- Creation by Plants

- Creation from Objects

Category 2: Creation Procedures

- Creation from Emergence

- Creation by Huasheng (Metamorphosis)

- Creation by Transformation

- Creation by Birth from Egg

- Creation by Production

- Creation by Marriage

- Creation by Pregnancy

- Creation by Gansheng (Induction)

Category 3: Creation Results

- Creation of the Universe

- Creation of all Things

- Creation of the First Humans

- Order

- Other

A large issue with many of these stories is that the orally transmitted nature of the tales makes it difficult to pinpoint their origin. For example, there are countless minority cultures, within and around what has historically been considered China, that have their own iterations of the Pangu myth. This has made it difficult to state where exactly the myth originated though it can be assumed that cross-cultural exchange between many of these peoples led to the formation of the Pangu myth as documented in the Three Kingdoms period[13]. Although there are far too many origin stories in the whole of China to create a completely exhaustive textbook chapter on, I will review one of particular interest from the Hani people, based primarily in the Yunnan province in Southern China.

The Hani people tell a story in which the universe was previously a vast ocean which over time would run out of food sources. This lead the Dragon King to send Minister Frog to produce heaven and earth with her excrement, chewed bones, and foams she spit during delivery of her children. After childbirth she became paralyzed and her two children, the male named Na De and female A Yi, used these materials to produce the earth which would float atop the boundless ocean. Their mother then made them remove her arm and use it as a pillar that Na De climbed and use his excrement to produce heaven while A Yi continued to work on the earth. Na De later gave birth to a girl from his anus, which prevented him from working and led heaven to be much smaller than earth. A Yi criticized him for this and in frustration he lashed back at her asking if she knew what it was like to give birth. This exchange ultimately passed the job of childbearing from men to women. When this job was done the mother frog strangled herself, ordering her children to use her eyes to create the Sun and Moon and her blood and fragments of her corpse to create the stars, clouds, mist, wind, and rain. After the earth’s completion the Dragon King sent animals from the ocean which lived on both water and land but supposedly still retain their swimming ability. He also granted frogs the ability to live in both land and water for their sacrifices, though he refused to transform Na De and A Yi into humans, which is why frogs croak during the rain in resentment.[14] There are many unique features about this story as compared to any described previously. Most notably, heaven and earth are not created by any deity, or born from a raw chaotic energy, but are created by animals. Interestingly the story does not tell the origin of the universe as a whole, as Westerners may expect from such a story, but the world we humans live in today, with the implication that there was a world before this one. However there are certainly similarities to the stories of Pangu in both the idea of separation of binaries (male and female, heaven and earth), as well as the transformation of a corpse into elements of our world. This demonstrates that Chinese culture is far more multifaceted than we may expect, with its values being understood and interpreted by a variety of different distinct cultural groups.

Though the study of Chinese creation myths has been neglected in the West, the myths are valuable tools to help understand the depth and diversity of Chinese culture. They also provide an interesting look into the way in which Chinese culture has constantly been evolving throughout history as well as how elements of cultural exchange create complex narratives. Finally, the study of Chinese creation myths truly exemplifies just how important the spoken word can be as a historical document, with storytelling practices helping us to fill in the blanks that the past has left muddled.

Bibliography

Goldin, Paul R. “The Myth That China Has No Creation Myth.” Monumenta Serica 56 (2008): 1-22. www.jstor.org/stable/40727596.

Schipper, Mineke, Ye, Shuxian, and Yin, Hubin, eds. China’s Creation and Origin Myths : Cross-Cultural Explorations in Oral and Written Traditions. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Wu, Bing’an. “Chinese Creation Myths: A Great Discovery.” In China’s Creation and Origin Myths: Cross-Cultural Explorations in Oral and Written Traditions, edited by Mineke Schipper, Shuxian Ye, and Hubin Yin, 179–96. Leiden: Brill, 2011. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/muhlenberg/detail.action?docID=717600.

Yu, David C. “The Creation Myth and Its Symbolism in Classical Taoism.” Philosophy East and West 31, no. 4 (1981): 479-500. doi:10.2307/1398794.

- David C Yu, "The Creation Myth and Its Symbolism in Classical Taoism," Philosophy East and West 31, no. 4 (1981): 479-480. ↵

- Yu, "The Creation Myth," 479. ↵

- Yu, "The Creation Myth," 479. ↵

- Yu, "The Creation Myth," 480. ↵

- Yu, "The Creation Myth," 481. ↵

- Yu, "The Creation Myth," 483. ↵

- Paul R. Goldin, "The Myth That China Has No Creation Myth," Monumenta Serica 56 (2008): 4-5. ↵

- Goldin, "The Myth That China Has No Creation Myth," 10. ↵

- Goldin, "The Myth That China Has No Creation Myth,"20-21. ↵

- Mineke Schipper, Shuxian Ye and Hubin Yin, "Preface," in China's Creation and Origin Myths: Cross-Cultural Explorations in Oral and Written Traditions, edited by Mineke Schipper, Shuxian Ye and Hubin Yin (Leiden: Brill, 2011), xiv. ↵

- Schipper et al., "Preface," xii. ↵

- Wang Xianzhao, "Minority Creation Myths: An Approach to Classification," in China's Creation and Origin Myths, ed. by edited by Mineke Schipper, Shuxian Ye and Hubin Yin (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 197. ↵

- Bing’an Wu, “Chinese Creation Myths: A Great Discovery,” in China’s Creation and Origin Myths, ed. Mineke Schipper, Shuxian Ye, and Hubin Yin (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 292-93. ↵

- Mineke Schipper, Shuxian Ye, and Hubin Yin, eds., “Heaven and Earth Created by a Frog: Hani,” in China’s Creation and Origin Myths: Cross-Cultural Explorations in Oral and Written Traditions (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 319–22. ↵