17 Buddhist Hell: Overview and Structure

Kayleigh Durning

Key terms

- Buddhist Hell

- Purgatory

- Karma

- View of the afterlife

- Rebirth

When one hears the term “Buddhism”, one usually associates it with non-violence, enlightenment and maybe even nirvana. However, upon relating it back to the term karma, a belief that most people are familiar with, it becomes no surprise that medieval Chinese Buddhism creates an afterlife focused on retribution in an equal manner to the sin which the person committed in their life. This new view of the afterlife was a drastic change from that which existed before the rise of Buddhism; it changed how ancestors were viewed, the requirements of descendants, and created many tensions because of the major changes, but also affected the actions of those still living. The specific details of Buddhist hell have been illustrated through history texts, as well as pieces of art. Some of the literature that describes these images of Buddhist hell are stories of those who have traveled through it and returned to the land of the living to tell the tale.

Pre-Buddist and Buddhist Views of the Afterlife

Before the arrival of Buddhism in China (first century CE) and its popularization, the view of the afterlife was quite grim. The rich could look forward to an afterlife full of entertainment and other luxuries that their descendants could bury them with, but the poor could only envision being stuck in a tomb for eternity. Buddhism changed this mindset drastically because the dead were no longer damned to live in cramped, wet tombs for the rest of time, they could be reincarnated based on their karma. So, the quality of one’s afterlife is based on their own actions; they control their own fate [1]. However, the heinous tortures of Buddhist hell aimed to influenced people’s actions and made them think twice before straying from the path outlined in Buddhism by sinning. One thing that remained constant before and after Buddhism was the presence of bureaucracy [2]. This stayed an obstacle that the common people had to endure.

Emergence of Buddhist Hell

The Buddhist text “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” shows the birth of a new concept of the afterlife in medieval Chinese Buddhism. This new vision of the afterlife is parallel to the medieval European concept of purgatory, which may be defined as “the period between death and the next life during which the spirit of the deceased suffers retribution for past deeds and enjoys the comfort of living family members” [3].

Structure of Buddhist Hell

When one enters hell, they must pass through the tortures of ten kings, one after the other [4]. Each king distributed retribution, inflicting a punishment that was meant to be equivalent for the sins which the person committed during their life [5]. The tortures and trials inflicted for one’s conduct in life were continually more painful as they moved through the procession of kings, meeting a new one every seven days. After week seven, the person would be seen by the king of Mt. Tai, and at this point they would either have the chance to leave the underworld, or stay if they’re still found guilty [6]. If they were still found guilty, they passed before the remainder of the kings, eight, nine and ten for one hundred days, one year, and three years respectively. If at king seven, or after reaching king ten it was decided that they could leave, they would be reborn as either a god, titanic demon, human, animal, hungry ghost, or denizen of hell [7].

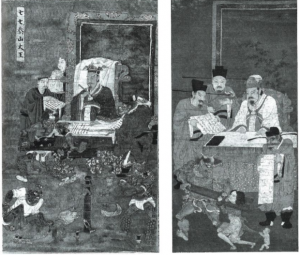

Bureaucracy is one aspect of life that is still prevalent in this afterlife. The ten kings functioned as a jury or judge of sorts. One of the parts of the bureaucracy is that if you were a government official in life, or someone seen as “honest”, you got a high position in the underworld after death too [8]. So, the common people still could not escape the rule of those seen as superior to them. The structure of Buddhist hell is often depicted with the Kings above those being judged or tortured. This emphasizes their power over the mere common people and depicts the bureaucracy as they are seen in a god-like position, presiding over, and judging other men who are seen as inferior to them. One parallel between the earthly and underworld jurisdictions is the story of the famous judge Bao. After dying in 1062 CE, he left this world and became the Director of the Court of Prompt Retribution of Mount Tai [9]. He earned this position because of his exemplary honesty in life.

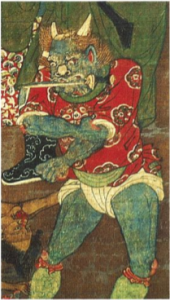

There are many different layers of hell based on the transgression committed during life. Two, for example, are the Mountain of Knives, full of vertical blades, and the Forest of Swords [10]. Those in the Forest of Swords, for instance, were sent there because they violated temples and monasteries in their life.

One extraordinarily similar piece of literature is “Dante’s Inferno”, part of the Divine Comedy. This follows author Dante Alighieri’s journey through the levels of the Inferno, or hell, where people are sent based on their sins, exactly like in Buddhist hell. For example, level six is for the heretics. These people are punished by remaining in burning tombs for the rest of their existence because their beliefs or actions deviated from that of the orthodox church at that time; they committed heresy.

This knowledge about Buddhist hell and its structure can be supplemented by stories of people who went into the afterlife and returned to tell the tale. One of these stories is that of Mulian who goes looking for his mother who was sent to hell for her transgressions [11].

Overall, the arrival of Buddhism brought some of the same concepts that the Chinese were used to, such as a hierarchical system; but it also changed many others. The idea of Buddhist hell provided both hope for the less wealthy because they could control their fate through their actions in life, but also terror. The tortures used in Buddhist hell were brutal, and since bureaucracy was still present, the fate of the common man was still decided by figures of wealth and status, just as it was during life. So, this unfair starting ground still left the common people at a disadvantage, but the idea of karma helped to try and even the playing field.

How to expand this chapter

- Expand upon the Mulian story, or other tales of people who have gone into Buddhist hell and returned;

- Expand upon the artistic adaptations that have been made regarding Buddhist hell.

Bibliography

Alighieri, Dante. Inferno. New York: Fall River Press, 2018.

Braarvig, Jens. “The Buddhist Hell: An Early Instance of the Idea?” Numen 56, no. 2-3 (2009): 254–81.

Mair, Victor H., Nancy Shatzman. Steinhardt, and Paul Rakita Goldin. Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005.

Silk, Jonathan A. Riven by Lust: Incest and Schism in Indian Buddhist Legend and Historiography. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009.

Teiser, Stephen F. “‘Having Once Died and Returned to Life’: Representations of Hell in Medieval China .” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 48, no. 2 (December 1988): 433–64.

Teiser, Stephen F. The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2003.

“The Quest of Mulian, or The Great Maudgalyāyana Rescues his Mother from Hell”. In An Anthology of Translations: Classical Chinese Literature. Vol. 1: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, edited by John Minford and Joseph S. M. Lau, 1088-1110. New York: Hong Kong: Columbia University Press; The Chinese University Press, 2000.

- Jens Braarvig, ‘The Buddhist Hell: An Early Instance of the Idea?’, Numen 56, no. 2/3 (2009): 225. ↵

- Lothar Ledderose, Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art, Bollingen Series, XXXV : 46 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 184. ↵

- Stephen F. Teiser, The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism, Kuroda Institute Studies in East Asian Buddhism 9 (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1994), 1. ↵

- Teiser, The Scripture on the Ten Kings, 2. ↵

- Jonathan A. Silk, Riven by Lust: Incest and Schism in Indian Buddhist Legend and Historiography (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 25. ↵

- Ledderose, Ten Thousand Things 164. ↵

- Braarvig, "The Buddhist Hell," 256. ↵

- Ledderose, Ten Thousand Things, 184. ↵

- Ledderose, Ten Thousand Things, 184. ↵

- Ledderose, Ten Thousand Things, 165. ↵

- “The Quest of Mulian, or The Great Maudgalyāyana Rescues his Mother from Hell,” in An Anthology of Translations: Classical Chinese Literature. Vol. 1: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, edited by John Minford and Joseph S. M. Lau (New York: Hong Kong: Columbia University Press; The Chinese University Press, 2000), 1088-1110. ↵