13 Terracotta Warriors: The Past and the Present

Sabrina Pfeiffer

Key terms

- Terracotta warriors

- Qin Dynasty

- Qin Shi Huang (the First Emperor)

- Xi’an, China

Most people believe that there are seven wonders of the world, but there are many others in the world who believe there are eight wonders of the world; the eighth is an eight-thousand army of warrior statues that were hidden underground for over two-thousand years. That army is called the Terracotta Warriors and they were placed there to protect the First Emperor of China during the Qin Dynasty, Qin Shi Huang. In this textbook chapter, we will go through what the Qin dynasty was, who the Qin emperor was, and why he deserved the tomb. We then will get into the facts of the tomb, its different sections, and what is in each section. Finally, we will delve into the present day and talk about the archaeology of the tomb and the facts of the excavation of it.

History of the Qin Dynasty

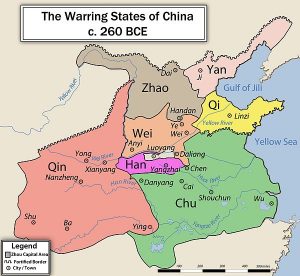

Before we understand what the tomb is, we first have to understand why it was built and for whom. Qin Shi Huang was the ruler of the Qin Dynasty, and he was the first to unite all of China. He was a very powerful and ruthless man according to a lot of scholars. In 256 BCE, the Qin took over the Zhou dynasty, one of the first major dynasties they took over. Then from 230-221 BCE, they took over the states of Han, Zhao, Yan, Wei, Chu, and Qi. [1]. Out of all these, Chu was the hardest for them to conquer and took the longest to do so because they were almost as powerful as the Qin. One reason for this was that they were actually very lucky geographically. The Qin’s base on the west was protected with three mountains surrounding it. There was only one way in and out, making it much easier to keep it secure. The Qin was also very innovative. They created a standardized, but very powerful, crossbow that anyone, with a couple of days of training, would be able to use and fight with. [2]. This made their army so much bigger because now non-military people could also fight in the war. The last thing they did that put them over the edge to winning was the fact that they were willing to accept help from outside their borders, while other states were not. Qin Shi Huang finally unified all the Warring States into one state, stopping most of the fighting and laying the early foundation for what we know now as modern-day China.

Even after they won, the Qin made sure to keep making a name for themselves and the way they did that was building major projects (the tomb being one of them, obviously). Another of these major projects was a great wall, which is different from the Great Wall of China we have today, but it was the inspiration for the modern-day Great Wall of China. The Qin also created a 500-mile highway so they could move their army around the country very easily. The Qin has contributed so much to not only Chinese history but World History, and that is mainly because of who their leader was, Qin Shi Huang. [3].

It is clear to scholars that Qin Shi Huang had an immense amount of power from what he ordered his people to do for him. Once he was in control of all of China, he forced 120,000 families to leave their lives wherever they were and move to the new country capital, Xianyang. He also called for and demanded 700,000 people to build his tomb. [4]. He knew how much power he had and used it to his advantage.

Terracotta warriors and the tomb of the First Emperor

Qin Shi Huang began building his tomb near Xi’an, China, a city located 1114 km (692 mi) southwest of Bejing, when he and his dynasty took over all of China. 37 years later, when Qin Shi Huang died, construction ended and he was put into the tomb [5]. There are about 180 pits that have been found so far, most of which haven’t been excavated, but archeologists are not convinced they have found them all. [6] This tomb was not just a tomb, but an underground world that Qin Shi Huang could live in for the rest of eternity with an entire army, the terracotta army, to protect him. The terracotta army took up three pits (a fourth is empty), which were located a few miles to the east of the emperor’s final resting place. The pits containing the terracotta warriors have been mostly excavated and they are what historians and archeologists have learned the most about since the site has been found. The first pit is the biggest and contains about 6,000 warriors. The second is an L-shaped pit and, although it is smaller than the first, it is much more complicated because the warriors in this pit were set up in battle formation. The third and smallest terracotta warrior pit was U-shaped and was believed to be the ‘headquarters’ for the terracotta army. Archeologists also found pottery, chariots, horses, and weapons in the third pit. [7]. There was a fourth pit for the terracotta army that was found, but it was empty. It is thought that warriors were meant to go into it, they just did not have the time to do so before Qin Shi Huangdi passed.

Obviously the size of this creation is one thing that makes it so great, but it is also the attention to detail that just puts it over the edge. The terracotta army had bodies, armor, and weapons that were mass-produced; however, heads and faces were unique to each warrior and made by hand. Each weapon that was made for this army was fully functioning and had never been used, meaning each piece of each weapon was made specifically for Qin’s afterlife army. [8].

The people who worked on this remarkable site ranged from convicts and/or people who owed money to the government, to artisans who were commissioned to create the beautiful art, or should I say statues. They were all treated very poorly and many of them died on site. There are quite a few mass graves that have been found on the tomb grounds that are believed to be these poor people and felons.

The main pit, the pit containing the tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi, has a 52-meter tall, man-made mountain on top of it to hide it. [9]. Although it has not yet been excavated, there have been many speculations scholars have made throughout history. The first record is from roughly 120 years later by a historian of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), Sima Qian. He wrote that the chamber contained rivers of mercury and constellations made of candles that were burning whale oil so they could burn forever. It is thought that it is not just a tomb down there, but an underground, awe-inspiring palace that the Emperor can live in for all of eternity. [10].

The most interesting aspect of this, in my opinion, is the fact that the Emperor created a second life for himself for after he died. When we get to see what he commissioned for his afterlife, which was a continuation of his life on Earth, historians and archeologists get to learn about the Emperor’s life in Ancient China.

Present-Day archaeology of the tomb

The tomb was not known about for roughly 2000 years until 1974 when a man named Yan Zhifa was trying to find better land to farm in and started digging. [11]. He found pieces of bronze and terracotta. Archaeologists have been digging and excavating ever since. They have only explored a few of the hundreds of pits they have found, and they believe that there are even more they haven’t found.

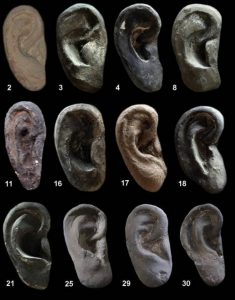

Today, archaeologists are doing a lot of work in Xi’an, China. They have come up with and have used a lot of different aerological techniques to learn about and understand the terracotta army and the Qin dynasty. They have and are using a piece of technology that takes the 2D images they take of the statues and make them into a virtual 3D image. This way they can electronically compare all the statues without too much hassle. It was through doing this that archaeologists have found the uniqueness of all the soldiers. For example, they know now that all the soldiers have 1 of 20 different kinds of ear lobes. [12].

If you were to take a trip to Xi’an China today, you would find the museum entitled “Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum”. [13]. Although there is a lot of archaeological work and excavating that still needs to be done to the Terracotta Army and its underground kingdom, many people and tourists around the world come to see the impressive and monumental pits that are open.

A Few Extra Fun Facts

- The word China actually is derived from Qin. [14].

- The molds for the legs of the terracotta army were actually drain-pipes. [15]

- The second emperor had all the women from the first emperor’s harem who bore no sons during the reign of the first emperor be buried alive in the tomb since it would be “unfitting” if they were sent elsewhere. [16].

- The word “terracotta” means a type of clay that these statues were made of. The rest of the statues and figures are made of bronze or wood.

Bibliography

“Emperor’s Ghost Army.” Directed and produced by Ian Bremner. Public Broadcasting Service, 2014. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7C2800639

“Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum.” Exhibitions. http://www.bmy.com.cn/2015new/bmyweb/show.html.

Portal, Jane, Hiromi Kinoshita, Jane Portal, and Hiromi Kinoshita. The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Rossabi, Morris. A History of China. 1 online resource vols. The Blackwell History of the World. Chichester, West Sussex ; Wiley Blackwell, 2014.

Sima Qian, “Chapter 6: The Basic Annals of Qin”. In Records of the Grand Historian, translated by Burton Watson, New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1993.

Sun, Yan. “Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huangdi.” In Berkshire Encyclopedia of China: Modern and Historic Views of the World’s Newest and Oldest Global Power, edited by Linsun Cheng. Berkshire Publishing Group, 2009, via Credo Reference.

- Morris Rossabi, A History of China, 1 online resource vols., The Blackwell History of the World (Chichester, West Sussex ; Wiley Blackwell, 2014), 62. ↵

- "Emperor's Ghost Army," directed and produced by Ian Bremner, PBS, 2014, 31:00. ↵

- Rossabi, A History of China, 64. ↵

- Jane Portal et al., The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2007), 117. ↵

- "Emperor's Ghost Army," 11:00. ↵

- Yan Sun, “Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huangdi," In Berkshire Encyclopedia of China: Modern and Historic Views of the World’s Newest and Oldest Global Power, edited by Linsun Cheng, via Credo Reference, 2009. ↵

- Sun,“Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huangdi.” ↵

- "Emperor's Ghost Army" ↵

- Sun, “Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huangdi.” ↵

- Sima Qian, “Chapter 6: The Basic Annals of Qin”. In Records of the Grand Historian, translated by Burton Watson, (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1993), 63-64. ↵

- "Emperor's Ghost Army," 7:00 ↵

- "Emperor's Ghost Army," 21:00. ↵

- “Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum.” Exhibitions, http://www.bmy.com.cn/2015new/bmyweb/ ↵

- "Emperor's Ghost Army." ↵

- "Emperor's Ghost Army," 18:23. ↵

- Sima Qian, “Chapter 6: The Basic Annals of Qin”. In Records of the Grand Historian, translated by Burton Watson, (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1993), 63-64. ↵