Eva Vaquera

After a multitude of attacks and military intimidation, Japan annexed Korea in 1910, marking the beginning of Japanese colonization in Korea.[1]. Take, for instance, the labeling of traditions. Japanese colonial authorities referred to native tradition as dozoku, native custom, or minzoku, folk custom. The use of the word "native'' is meant to portray Koreans as “backward, irrational, and emotional peasants” and as “uncivilized and uncultured."[2] With such a portrayal, the Japanese could justify the erasure and or destruction of Korean culture “under the name of colonial modernity.”[3]

Shamanism in Korea

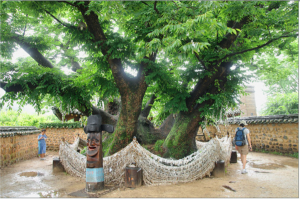

Taking into consideration the superiority complex of the Japanese over the Koreans, one must wonder how that came to play in colonial society. A popular belief in Korea during such a period was shamanism, an animistic ethnic religion.[4] It is referred to as a "practice that has continued from the very moment Korea came into existence."[5] Given shamanism’s longevity in history, the religion has influence from Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.[6] While the main focus of this chapter is the role of shamanism in the colonial period, Confucianism plays a critical role in Korean society, specifically its role in the treatment of those who practice shamanism. Taking this in consideration, we should note within Confucianism the hierarchical nature of relationships. For example, the power relationship between ruler and subject, father/son (parents/children), husband and wife, etc. In sum, loyalty is an important aspect in traditional Korea/East Asia as a result of Confucianism's influence in society. Now, back to shamanism. The religion includes the worship of gods, ancestors, and nature spirits. It is thought to date back to prehistory, which is way before the conquest of Korea by the Japanese. The difference between shamanism and Confucianism is that “while Confucianism emphasizes state authority, a hierarchical social order, knowledge, and education, shamanism generates an ideology of egalitarianism and provides the symbolic experience of liberation from differentiation and the yoke of lived reality.”[7]

While anyone can practice shamanism, there are "chosen" individuals called shamans, or mu in Korean.[8] Through different sources, shamanism is described to be dominated by mudangs, who act as intermediary between spirits or gods and humanity to solve problems that come up through life.[9] Mudangs do this through the practices of guts, which are rituals officiated by a shaman, with a table of sacrificial offerings, gutsang, for the gods, and accompanied by song, dance, music and performance. Shamans are believed to have been chosen by gods or spirits through a spiritual passage known as shinbyeong, "divine illness," which is a form of ecstasy and entails the possession from a god and a "self-loss.” Shinbyeong is described to manifest in symptoms of physical pain and psychosis. It is also characterized by a loss of appetite, insomnia, and visual and auditory hallucinations. The only way to heal from these pains is by accepting a full communion with the spirit, also known as naerim-gut. It serves both to heal the sickness and to formally establish the individual as a shaman. There are other forms of gut, which are rites performed by shamans involving offerings and sacrifices to gods, spirits, and ancestors. The characteristics of guts are rhythmic movements, songs, oracles and prayers. All are meant to create welfare and promote commitment between the spirits and human kind. The manner in which shamanism was practiced fueled Japan’s intentions of displaying superiority over Korea as the shamanic ritual performances were described as “vulgar, coarse” with “uncivilized language and drama."[10]

During Japanese occupation

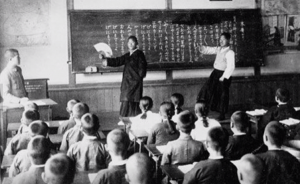

With an increased perspective of superiority and the need of assimilation, Japanese colonial authorities began to force Koreans to pay respect to fallen Japanese soldiers, reiterating that the Japanese were the only ones that mattered.[11] Additionally, there was an emphasis on watching over congregating Koreans, specifically when there were a large number of them. Typically, Koreans would be forcibly removed from the area and punished physically. As violence increased, the Japanese government began to target a multitude of societal aspects, other than religion.[12] This included for instance forcing Koreans to learn Japanese as a means to make communication between the two nations easier, but more importantly, to eliminate the Korean culture.[13]

Interestingly, Koreans resisted these attempts of assimilation by using these Japanese stereotypes and generalizations for their own gain.[14] Take the previous example, Koreans would typically use the generalization that they were too uncivilized to learn the great language of Japan, avoiding assimilation a little longer. However, these forms of resistance, while successful, did not eliminate or halt the increase of violence toward Koreans, specifically those practicing “fake religions."[15] Shamanism fell under such a category. “Shamans were arrested and threatened by the police to give up their practices because it was thought that they were fostering social instability and unhealthy living in the innocent populace.”

Moreover, shamanism became a “major target of Japanese criticism because of its noise, lavish consumption, superstitious life, and its anti-social order ideas and behavior. Again and again, shamanic rituals revived hungry ghosts, entities who have voices to the Koreans and expressed the miserable material conditions and grievances against colonial exploitation.”[16] Through several campaigns and educational programs, the Japanese attempted to eliminate shamanism.[17] However, shamans resisted. When the colonial government forced Koreans to change their name to Japanese, shamans resisted by stating that spirits wouldn’t understand Japanese because “they were not Japanese subjects.”[18] Not all shamans refused, some of them changed their name from Korean to Japanese and learned the language. These individuals were favored by Japanese police but despised by fellow shamans.

With such rebellious acts from shamans, one would not expect Japan to allow Koreans to practice their religion. Such a thing did not occur. Instead, the Japanese tried to incorporate shamanism into Shinto.[19] The thought process was that it would be “an effective way to control the colonized peoples’ minds and achieve cultural assimilation.”[20] There was some cooperation in this aspect as Tan’gun, the (mythological) first Korean and the supreme shaman, and Amaterasu Ōmikami, the Japanese goddess of the sun and an important deity in Shinto, would be be displayed together in a shrine.[21] However, such cooperation quickly fell through as there was debate if the two figures were equal or one was superior to the other. In the end, “the colonial government… forced Koreans to accept the hierarchical order of the deities and thus the superiority of Japan over Korea.” Shinto shrines were placed in every district, eventually leading to roughly 850 shrines by the end of the period of Japanese control.

It should be noted that the Japanese were not the only ones targeting shamans, but Confucians and Christians, along with others, “were supporting colonial efforts to destroy shamanism because they were critical too.”[22] Additionally, shamanism was also considered to be an enemy to these previously mentioned religions, leading the communities to reluctantly cooperate with the Japanese.[23] While there is a difference between ideologies among these communities, Koreans did not jump on the bandwagon to go against each other. More likely, several Koreans were forced to go against one another as a means of survival under colonial rule. There are several stories in “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul” that tell of Koreans' violence against one another while facing consequences for their refusal to oblige under Japanese rule, like a Korean interrogator slapping a shaman for practicing his religion.

In the end, under Japanese rule, Korea was forced to acknowledge its vast differences between itself and Japan while simultaneously understanding its similarities with Japan. One can see this when learning about shamanism during the colonial period. Targeted for its “violent” and “uncivilized” practices, shamanism became a form of resistance against colonial authorities, eventually leading to the Japanese incorporating shamanism into Shinto practices to ease assimilation. Through the constant attack for practicing the religion, “shamanism did not maintain its original form and nature.”[24] While it continued to hold the cultural root in practice (ie. shamans being a medium between the real world and the after life), shamanism became a political symbol of resistance dependent on the perspective of local scholars, intellectuals, and Japanese scholars.

Epilogue

Despite the constant attack to eliminate, shamanism persevered into the 21st century. Shamanism continues to be present in the peninsula. In the South, “shamanistic rituals are visually flashy and involve a lot of sound.”[25] In the North, the rituals and practice of shamanism is more reserved and quieter because it is “considered an illegal superstition whose practitioners can be jailed or executed.”[26] With the rise of other religions in Korea and the world, it will be interesting to see if and how Shamanism continues its presence in society. Will it be eliminated or will it continue to resist?

Bibliography

Including works consulted and suggestions for further reading.

“Amaterasu.” 2022. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amaterasu.

Blakemore, Erin. 2018. “How Japan Took Control of Korea.” History.com. A&E Television Networks. February 28, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/japan-colonization-korea.

Hwang, Merose. “The Mudang: Gendered Discourses on Shamanism in Colonial Korea.” PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2009.

“KEY POINTS across East Asia-by Era.” Asia for Educators, Columbia University. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/main_pop/kpct/kp_1900-1950.htm#korea-changes.

Kim, Kwang-Ok. “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul: Religion as a Contested Terrain of Culture.” In Colonial Rule and Social Change in Korea, 1910-1945, edited by Hong Yung Lee, Clark W. Sorensen, and Yong-Chool Ha, 264–313. University of Washington Press, 2013.

“Korean Shamanism.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_shamanism.

"Korean Shamanism" (website) https://shamanism.sgarrigues.net/.

“Korea Under Japanese Colonial Rule", KI-ŎK (website) http://www.ki-ok.org/korea-under-japanese-rule.

Kuhn, Anthony. “In Korea, Shamanism Remains Important In The North and South.” NPR, May 1, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/05/01/992670177/in-korea-shamanism-remains-important-in-the-north-and-south

“Shinto.” Asia Society (website). https://asiasociety.org/education/shinto.

- For more information about the Colonial Period, see the Chapters "The Colonial Period in Korea" and "Colonial Korea and Nationalism" With the annexation, Japan wanted to showcase their power over the Korean Peninsula, and essentially the world. There were multiple instances in which Japanese authorities intended to discredit Korean culture and assimilate the country into Japanese culture, displaying superiority over the country.[footnote]Kwang-Ok Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul: Religion as a Contested Terrain of Culture,” in Colonial Rule and Social Change in Korea, 1910-1945, ed. Hong Yung Lee, Clark W. Sorensen, and Yong-Chool Ha (University of Washington Press, 2013), 264. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 265. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 265. ↵

- Animism is the belief that objects, places, and creatures possess distinct souls. Essentially, everything on earth is perceived as animated and alive. ↵

- Merose Hwang, “The Mudang: Gendered Discourses on Shamanism in Colonial Korea.” (Toronto, University of Toronto, 2009), 1. ↵

- For a refresher, Daoism is a religion from China that puts an emphasis on living in harmony between yin and yang, but above all: a big pantheon of gods, spirits, and demons which the priest has to work with (or against), using a variety of rituals. Next, Buddhism is a religion which is first recorded in India, that believes one must overcome suffering caused by desire and ignorance of reality's true nature. It emphasizes the Four Noble Truths: "all life is suffering" (truth of suffering), "there is an origin to the suffering" (truth of arising), there is an end to the suffering (truth of cessation), and "the eight-fold path leads to the ending of suffering" (truth of the path). The eight-fold path is the final step for a Buddhist to accomplish the Four Noble Truths. Finally, Confucianism is a Chinese belief that is said to be a system of behavior and thought, and describes human beings as being fundamentally good and teachable, improvable, and perfectible through personal and communal effort, especially self-cultivation and self-creation. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 265. ↵

- Previously, it was mentioned that mu means shaman in Korean. While that is true, there are different labels to describe shamans based on their binary gender. For female practitioners, the label is mudang. For men, the label is baksu. ↵

- Mudangs were described to be women who mediate or channel spirits of the deceased in the interest of spirits or the living. Hwang, “The Mudang,” 3. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 265. 266. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 266. ↵

- Education began to be limited until Koreans were no longer receiving up-to-date knowledge. On the other hand, the Japanese continued to receive knowledge, leading Koreans to believe that they had lost their nation. See also chapters xx ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 280-281: “The Japanese Government-General denounced the Korean languages, aesthetics, and folk customs while it promoted the Japanese lifestyle in the discourse of sanitation, science, and civilization… Shamans rationalized their practice of traditional customs by displaying their inability to efficiently adapt themselves to the Japanese way of like. They always proudly affirmed that they were illiterate and too stupid to master the Japanese language.” ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 272. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 273. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 285. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 283. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 297. ↵

- In Shinto, humans are thought to be fundamentally good, and evil is believed to be caused by evil spirits. Consequently, the purpose of most Shinto rituals is to keep away evil spirits by purification, prayers and offerings to kami, deities. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 286. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 287. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 279. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 290. ↵

- Kim, “Colonial Body and Indigenous Soul," 307. ↵

- Kuhn, Anthony. “In Korea, Shamanism Remains Important In The North and South.” NPR, May 1, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/05/01/992670177/in-korea-shamanism-remains-important-in-the-north-and-south ↵

- Kuhn, “In Korea.” ↵