Julian Goldman-Brown

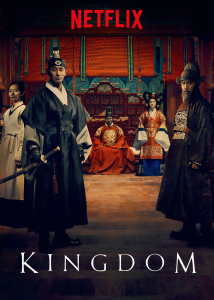

It’s fairly common nowadays for there to be movie adaptations of historical events. Some of these are meant to be direct retellings of the history, others take some liberties with the history while keeping some pieces in place, and then on occasion you’ll have some completely inaccurate blockbuster starring Matt Damon. For this chapter I decided to analyze the Netflix series Kingdom by Kim Eun-Hee, which is an adaptation of her webtoon The Kingdom of the Gods. My reason for picking this topic is because I have always enjoyed consuming different forms of media, and I wanted to see if this was accurate in its portrayal of events and/or ideas from this time period. I will try to remain as spoiler-free as possible in this chapter in case anyone decides they want to watch the show. However, there are some things that I will share freely because they are needed to get a basic overview. If you decide you want to watch it I will warn you in advance: if you are squeamish this is not the show for you, as it is quite gory. On top of this, if you don’t like horror this might not be the show for you, depending on your tolerance for scarier media.

I’ll give a brief overview on the events in history that took place before this and then the events that happen in the show that drive its plot. The show takes place three years after the Imjin War (1592-1598).[1] The Imjin War was one of the greatest atrocities committed in history. The Japanese invaded Korea and they engaged in brutal warfare. The Japanese murdered, raped, and captured civilians. They mutilated bodies and burned the land, shrines, and temples. This show follows crown prince Lee Chang, as he deals with being framed for conspiracy against the king by the Cho family, so that they have no opposition. The King has fallen ill, and there is unrest because many people believe that the King is dead and that the Cho family, a powerful family that holds many positions in the government (but not actually part of the royal family), pretends he is alive in order to gain control over the country. They are correct, but there’s a twist. The King is the first zombie. He became this way because he had actually been sick prior, and the Cho family had a physician, Lee Seung Hui, come in to heal him. He brought with him a resurrection plant, which turned the King into a zombie.

From a true historical standpoint none of this happened. These characters didn’t exist, and there were no zombies in Korea. Kim Eun-Hee stated that in her research she had read about a mysterious disease that wiped out a large amount of people in Korea in a very short amount of time, and she thought that zombies would be a good replacement for the disease.[2] I tried finding records about this mysterious disease, but I couldn’t find anything. What is accurate in this depiction? Well, there are some parallels to figures in history with some of the characters in the show, but overall it is quite different in its portrayal of events. However, the way in which it tells the story and the ideas and beliefs embedded in the show, specifically surrounding death, are quite accurate to the format of stories that were published during that era, and the beliefs held by Koreans regarding death and the afterlife at the time.

During this time period Confucianism was extremely prominent, and this show uses those ideas. Confucianism didn’t outline an afterlife, so commemoration of the dead was deeply important, and it became emphasized after the Imjin War. Since there was no clear outlined afterlife, eternal life was achieved through remembrance and honor for the dead by the living. If the dead weren’t treated right, they were likely to wreak havoc.[3] The visuals for the opening credits and theme song depict a dead body being properly treated and they are constantly switching between shots of the body and shots of zombies. This is done to emphasize proper treatment of the dead versus improper treatment. The King was not allowed to die in peace in this show, and in trying to prolong his life he became a vengeful spirit, in this case represented by a zombie, which then led to the outbreak of the disease. The actual outbreak happened due to some gruesome circumstances. In the opening scene of the show we see a teen get dragged into the King’s chambers and partially consumed, which kills him. When the boy is brought back to his home town before his family can give him a proper ceremony his body is stolen and made into food, which was then fed to a large group of people by a person who told them it was a deer. They all soon fall ill and die after this, only to come back as zombies. Here again is another example of improper treatment of the dead creating chaos.

The story also has a structure similar to stories that talked about death that were recorded during the time period. The main difference is the stories I was able to look at were both dreams. However, this may not technically be a dream, but rather it is mystical. It follows what became the less common form of dream storytelling with a focus on the protagonist and his interiority, and it displays his growth over time. It does also pull from the other type of storytelling, more observer-based where the dead are given center stage.[4] When the story starts we can see that Prince Lee Chang does care about his people, but he has no concept of how to meaningfully interact with people, because as a prince he was raised in a very different environment. In the beginning of the story he will often alienate himself when he is among common people, because he doesn’t know how to talk to them in a way that isn’t condescending. While it does primarily focus on Prince Lee Chang as the protagonist, the story does often have scenes without him where the focus is on the growing threat of the zombies, or some other characters.

While this Netflix series is not accurate in its depiction of history, it is accurate in its representation of beliefs and ideas from this time period. It doesn’t make explicit mention in the dialogue of many of the beliefs surrounding death, but it is clear through the interactions that characters have, the tone, the imagery, and implicit dialogue that Kim-Eun-Hee did her research into the practices surrounding death during this era.

Bibliography

Haboush, Jahyun Kim. “Dead Bodies in the Postwar Discourse of Identity in Seventeenth-Century Korea: Subversion and Literary Production in the Private Sector.” The Journal of Asian Studies 62, no. 2 (2003): 415–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096244.

Kim Eun-Hee. Kingdom, Netflix, January 19, 2019-2022.

Sundriyal, Diksha. “The Real Inspiration Behind ‘Kingdom.’” TheCinemaholic, March 14th, 2020. https://thecinemaholic.com/kingdom-netflix-true-story/.

- For more information on the Imjin war, see also the two dedicated chapters in this textbook: The Imjin War, and Naming the Imjin War. ↵

- Diksha Sundriyal, “The Real Inspiration Behind ‘Kingdom.’” TheCinemaholic (website), March 14th, 2020. https://thecinemaholic.com/kingdom-netflix-true-story/ ↵

- Jahyun Kim Haboush, “Dead Bodies in the Postwar Discourse of Identity in Seventeenth-Century Korea: Subversion and Literary Production in the Private Sector,” The Journal of Asian Studies 62, no. 2 (2003): 419. ↵

- Kim Haboush, “Dead Bodies in the Postwar Discourse," pp. 419ff. ↵